From a memorial address given at St. Luke’s Church, Redcliffe Square, London, October 5, 1977.

I can recall being shy of meeting him, and perhaps others were too, because of that nimbus of authority that ringed his writings and his actions. In his fifties here in England, he already had the status of classic. Yet because of the way he divined us when we did meet him, he bound us to him as a person. In a room full of people, his quick scanning eyes could throw a grappling hook to the person he was meeting, as he came forward, half buoyant, half somnambulant, on the balls of his feet, his voice at once sharp and sidling. At those tentative moments, and on other more leisurely occasions when he could play the stops and pull the carpet in a conversation, he touched and strung in us a chord of fidelity and gratitude that we are gathered here to play once more.

That medieval phrase, “the fall of princes,” kept surfacing in my head for days after his death. Just as in that older dispensation the order and coherence of things were ratified in the person of the prince, so in the person and poetry of Robert Lowell the scope and efficacy of the artistic endeavor seemed exemplified and affirmed. He did not pitch his voice at “the public” but he so established the practice of art as a moral function within his own life that when he turned outward to make gestures against the quality of the life of his times those gestures had been well earned and possessed a memorable force. He alone had the right to call his conscientious objection to the Second World War a “manic statement,” but his open letter declining an invitation to the White House in 1965 was dignified and more potent than other, more clamorous, if equally well-intentioned, protests that followed.

He spoke at that time with a dynastic as well as an artistic voice, recalling how both sides of his family had a long history of service to the rem publicam, and this preoccupation with ancestry was a constant one. From beginning to end, his poems called up and made inquisition of those fathers who had shaped him and the world he inhabited. When he was a young poet graves and graveyards stirred his imagination, and there is a morose funerary splendor about his early meditations on the New England heritage: their rhetoric is both plangent and pugnacious, as they “lurch / for forms to harness Heraclitus’ stream.” The voice we hear in them is oracular and penitential, and its purpose is redemptive, as if by its effort toward understanding and its pining for transcendence it might conjure an “unblemished Adam” from what he was later to call “the unforgivable landscape.”

To the very end, memory remained for him both a generating and a judicial faculty. Indeed, I can think of no more beautiful evocation of its relevance to Robert Lowell’s life and work than those lines of T.S. Eliot’s, another New Englander making casts in Heraclitus’ stream:

This is the use of memory:

For liberation—not less of love but expanding

Of love beyond desire, and so liberation

From the future as well as the past. Thus love of a country

Begins as attachment to our own field of action

And comes to find that action of little importance

Though never indifferent. History may be servitude,

History may be freedom. See, now they vanish,

The faces and places, with the self which, as it could, loved them,

To become renewed, transfigured, in another pattern.

History, love, renewal, these were what possessed him, not as abstractions but as palpable experiences and consciously held-to categories of truth.

Yet he thirsted for accusation. That line in the concluding sonnet of The Dolphin which says, “My eyes have seen what my hand did,” branded itself upon me when I read it. It has two musics that contend but do not overpower each other. There is the bronze note, and perhaps even the brazen note, of artistic mastery, yet in so far as the words intimate the price which poetic daring involves there is also the still, sad music of human remorse. The man who suffers is recompensed in himself as the man who creates, but Robert Lowell, the man who spoke of “the brute push of composition,” was ruefully aware that that push could bruise others, others who were perhaps even the very nurtures of his poetic gift and confidence.

When I praised the line to him, he gracefully diverted the credit for it from himself and said, “Well, it’s something like what Hemminge and Condell said about Shakespeare, isn’t it?” But the line’s accusatory force derives from what they did not say: their sentence about Shakespeare reads, “His mind and hand went together,” and was meant to celebrate Shakespeare’s fluency and the felicity of his first thoughts and words. Robert Lowell bends and refracts all this to sustain the deliberated elements in his art, the plotting, as he called it, with himself and others, the unavoided injuries.

Advertisement

He was and will remain a pattern for poets in his amphibious ability to plunge into the downward reptilian welter of the self and yet raise himself with whatever knowledge he gained there out on to the hard ledges of the historical present, which he then apprehended with refreshed insight and intensity, as in his majestic poem “For the Union Dead,” and many others, especially in the collection Near the Ocean.

When a person whom we cherished dies, all that he stood for goes a-begging, asking us somehow to occupy the space he filled, to assume into our own life values which we admired in his, and thereby to conserve his unique energy. This feeling was made more acute for me by the fact that six days before he died, Robert Lowell and his wife had spent a happy, bantering evening with us in Dublin. I felt that something in our friendship had been fulfilled and looked forward to many more of those creative, sportive encounters. But his wise and wicked talk, his obsessive love and diagnosis of writing and writers, the whole ursine force of his presence have been withdrawn from us, as he half predicted they would be, in his sixtieth year.

We are things thrown in the air

alive in flight…

Our rust the colour of the chame- leon

This winter, I thought

I was created to be given away.

No honeycomb is built without a bee

adding circle to circle, cell to cell,

the wax and honey of a mauso- leum—

this round dome proves its maker is alive;

the corpse of the insect lives em- balmed in honey,

prays that its perishable work live long

enough for the sweet-tooth bear to desecrate—

this open book…my open coffin.

That almost narcotic thought of death can be felt in his latest poems, some of which were like prayers, acts of thanksgiving and of contrition, acts of hope for loved ones and of charity for himself. In a letter written last February we can catch a similar tone of resignation and the old indomitable irony:

The hospital business, despite the rough, useless and dramatic ambulance at MacLean’s, was painless, eventless; perhaps what death might be at its best. A feeling that one was doomed like Ivan Ilyich, but without suffering. Then there seemed to be no danger at all, except there may still be—but all so quiet it hardly seemed to matter…. If that’s all life is, it’s a coldly smiling anti-climax. Gone the great apocalypse of departure.

The last letter he wrote from Ireland, where he had spent time with his son Sheridan and with his stepdaughter Ivana, shunned the apocalyptic in favor of the playful: “I spent until about two with Sheridan. We had a merry amiable time except that he (wisely) preferred people to swans and a rubber tire swing to people.” I did not know Robert Lowell long or intimately, but these four lines found among papers he left behind in Ireland made me think of a man who could meet Charon, dart him one of those penetrating looks and allow himself to be guided, as of right, into the frail skiff:

Christ

May I die at night

With a semblance of my senses

Like the full moon that fails.

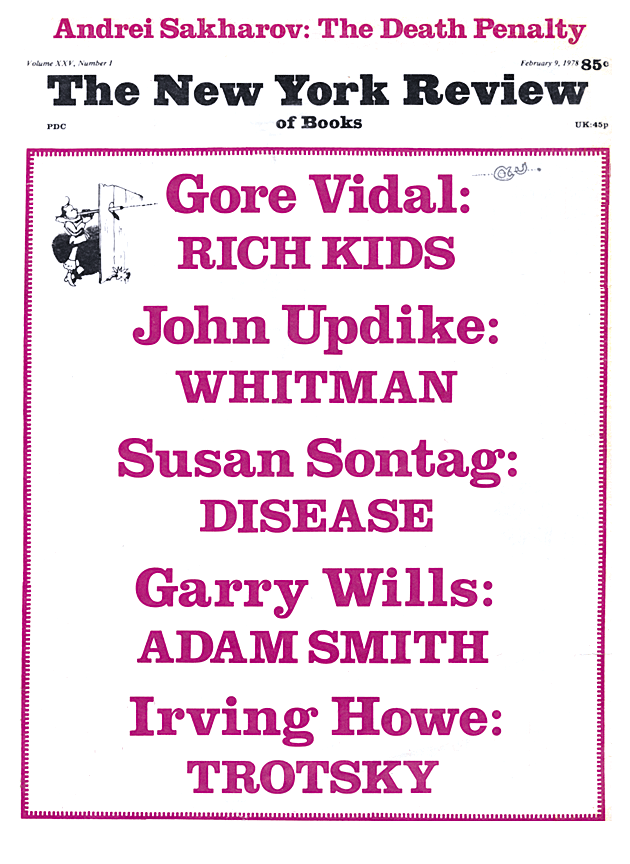

This Issue

February 9, 1978