In response to:

Who Can Salvage Peace? from the August 17, 1978 issue

To the Editors:

Stanley Hoffmann’s article, “Who Can Salvage Peace?” (NYR, August 17) rests on four errors: (1) that Israel has been reluctant or unwilling to make peace in accordance with Security Council Resolutions 242 and 338, especially with regard to the West Bank; (2) that (at the time Hoffmann wrote, at least) Sadat and other Arab leaders were willing to make peace in accordance with those Resolutions; (3) that Israel is seeking political control over “Arab lands”; and (4) that the United States missed an opportunity for peace in July, 1972, when Sadat purported to expel Soviet advisers from Egypt.

While often repeated, these propositions have no basis in fact.

Resolutions 242 and 338 require the parties to make peace by direct negotiations. Their agreements of peace should rest on two basic principles: Israel need not withdraw from any territories it occupied in 1967 until peace is made; and the new “secure and recognized” boundaries of Israel need not be the same as the Armistice Demarcation Lines of 1949.

I can testify from personal experience and subsequent study that Israel has cooperated in all the (many, many) efforts since 1967 to carry out Resolution 242. Until Camp David, all peace making efforts have foundered on the flat refusal of the Arab States to make peace in accordance with the Resolution. Even Egypt accepted only one-half the Resolution during Sadat’s trip to Jerusalem; the other Arab States continue to reject both halves. Sadat’s agreement at Camp David to make peace in three months, on the basis of a formula for the West Bank and the Gaza Strip which accepts the possible partition of those territories between Israel and Jordan, is a completely new development and a most constructive one. A reader would be hard pressed to appreciate the significance of this fact from Mr. Hoffmann’s article.

The most important reasons for the territorial provision of Resolution 242, which Sadat has just accepted in principle, is that the West Bank and the Gaza Strip are not “Arab” lands, but unallocated parts of the Palestine Mandate, a “sacred trust” like Namibia, to be fulfilled in accordance with its terms. Professor Hoffmann refers to the West Bank as “Jordanian territory.” This is not the case. Jordan’s attempt to annex the territory in 1951 was ineffective because it was not widely recognized by the world community, and especially by the other Arab states.

As Sadat has repeatedly made clear, his “expulsion” of some Soviet advisers from Egypt in July, 1972, was part of the Soviet-Egyptian deception plan in preparation for the War of October, 1973, on which the Soviets and the Egyptians had agreed in April, 1972.

Professor Hoffmann’s extraordinary comparison between France in the Thirties and Israel today is in a different category. It rests not only on factual error, but on errors of judgment. Hoffmann seems to believe that in 1935-1936 France could have prevented World War II by making a political agreement with Hitler. This is a fantasy. Surely Laval went “the extra mile” in his quest for agreement with Hitler. It is hard to imagine any concessions Britain and France could have made to Hitler beyond those they did make: the acceptance of German rearmament and the militarization of the Rhineland; and our non-intervention in Spain. The allies could have prevented the war not by more appeasement, but by occupying the Rhineland, by British conscription, and by a clear deterrent political policy, perhaps in association with the Soviet Union.

Mr. Hoffmann’s advice to Israel—that Israel should follow the course he thinks France should have followed when Hitler first came to power—simply boggles the imagination.

The agreements reached at Camp David contradict Mr. Hoffmann’s analysis in every particular. But his views are influential, and they continue to be heard and read.

Eugene V. Rostow*

Yale University Law School

New Haven, Connecticut

Stanley Hoffmann replies:

Mr. Eugene Rostow’s reading of past Israeli policy, of Egyptian policy in 1972, of the Camp David documents, and of what Sadat agreed to at Camp David, is as bizarre as his reading of my comparison between France in the Thirties and Israel.

The future will, I think, make it clear that no Arab state, including Egypt, wants a “partition” of the West Bank between Israel and Jordan, or accepts the idea that the West Bank and Gaza are not Arab lands.

As for my comparison, its only point was to show that in both cases, hard-pressed people mistakenly underestimated the costs of the course they preferred (appeasement in France’s case, continuing control of Arab lands in Israel’s) and overestimated the risks of a different course (resistance to Hitler in the Thirties, self-determination for the Palestinians today).

How Mr. Rostow could have misinterpreted my meaning is what boggles my imagination.

I do not believe that the Camp David agreements contradict my analysis. Obviously, it was Carter’s participation and pressure which wrested from Begin a number of significant concessions that go beyond the Begin plan of last December and that the Israeli government had refused to make before. It is also clear that only if the United States, in the months to come, interprets the ambiguous and controversial statements of Camp David in a way that satisfies the Arab states and the Palestinians, will there be a chance for real peace in the whole area.

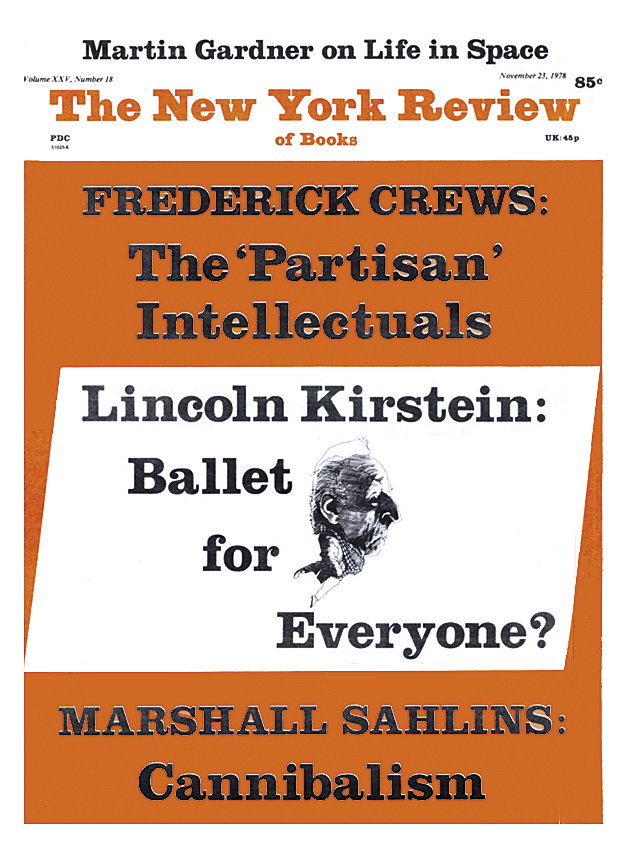

This Issue

November 23, 1978

-

*

While in the State Department, 1966-1969, I was in charge of the process which led to Resolution 242. ↩