In October 1943, the foreign ministers of Great Britain and the Soviet Union and the secretary of state of the United States of America met in Moscow to discuss a variety of territorial and other problems that would arise at the war’s end. In the course of these talks, they touched briefly on the future disposition of Austria, which had since 1938 been an integral part of the Great German Reich, and agreed without difficulty that—as their communiqué stated later—“Austria, the first free country to fall victim to Hitlerite aggression, shall be liberated from German domination.”

For Austria, the Moscow declaration was what the Germans call, after the soap powder, a Persilschein or certificate of purity, automatically absolving it from disabilities and punishments that would befall countries that were not “liberated” but designated as former enemies. Why the Big Three foreign ministers were so generous is still puzzling. A senior member of the US Foreign Service once suggested, not entirely frivolously, that it was because President Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill had spent happy summers in their youth rolling down Austria’s lush hills in lederhosen and were privately agreed that the Austrians were a jolly people who deserved much better treatment than the awful Germans. Others have wondered whether bad conscience was not at play, the Western Allies remembering that they had not lifted a finger to prevent the Anschluss in 1938 and had given de jure recognition to the new regime with altogether unseemly haste. The most likely explanation is that the foreign ministers were distracted by other problems (the war was far from being won, and the Soviet representative, Mr. Molotov, for example, seemed to harbor suspicions that his allies might be willing to allow Germany to keep some of its territorial gains as the price of peace) and that they were not fully aware of the implications of their declaration or concerned about its historical accuracy.

At the very least, their declaration was loosely phrased. Austria had, of course, been a sovereign state until Hitler’s tanks rolled into Vienna in March 1938, but that it had been free in any wider sense is more than questionable, in view of the fact that as early as 1934 the so-called Mini-Metternich, Engelbert Dollfuss, had revoked its democratic constitution, abolished parliamentary government, and established an authoritarian fascist state, and the further fact that his successor, Kurt von Schuschnigg, had not only continued this new order but used it to keep thousands of political dissidents in concentration camps.

Whether Austria could be described accurately as a victim of Hitlerite aggression was even more doubtful. The desire for union (Anschluss) with its northern neighbor was almost general in the country after 1918, and although this ceased to be true in the parties of the left after Hitler took power in Germany in January 1933, that event increased the passion for Anschluss in Austria as a whole. Its most unequivocal advocate was the Austrian National Socialist party, and it is significant that—as Bruce Pauley points out in his interesting and virtually unique history of that party—it was only after the Nazi victory in Germany that it became a mass movement, appealing not only to the lower middle class but also to “peasants, miners, Protestants, Catholics, civil servants, merchants, and artisans,” and particularly to intellectuals and students, so that the universities of Graz and Vienna became Nazi strongholds that made a major contribution to the country’s domestic unrest in the years from 1933 to 1938. During that time, the Nazis systematically disrupted Austrian politics for the purpose of creating a situation that would invite German intervention and make Anschluss inevitable and, despite all of Dollfuss’s and Schuschnigg’s efforts to contain them, by disabling legislation and police regulation, they were successful in the spring of 1938.

Mr. Pauley believes that the Austrian Nazi leaders would have preferred to take over power in Vienna by themselves and to effect the union without an actual military invasion; but when Hitler decided differently, neither their own followers nor most of the population seemed to be disappointed. A quarter of a million people crowded into Vienna’s Heldenplatz to greet the German Führer on March 15, 1938; half a million more lined the Ringstrasse to cheer him after his announcement of the Anschluss; and in the days that followed mobs in all of the country’s principal cities continued the celebratory mood by looting their Jewish fellow citizens, going about the job, as the German SS paper Schwarzer Korps wrote admiringly, “with honest joy” and managing “to do in a fortnight what we have failed to achieve in this slow-moving ponderous north up to this day.”

Nowhere in Austria was the acceptance of Hitler’s rule more enthusiastic and of longer duration than in Linz, the Upper Austrian entrepôt on the Danube where Adolf Hitler had grown to manhood at the turn of the century and from which, he once said, “Providence called me forth to the leadership of the Reich.” Evan Burr Bukey, in an excellent history of Linz in the modern period, describes the reasons for the strong grass-roots support that National Socialism enjoyed there from the moment of the Führer’s triumphant homecoming in 1938 until late in the Second World War. Hitler’s long-nurtured plans to transform his boyhood home into a major cultural center and the expedition with which Hermann Goering set about the job of restructuring its industrial base had much to do with this positive local response. Mr. Bukey writes that “the rapid introduction of measures relieving social distress, especially by the Strength Through Joy organization, the revitalization of the Linz economy, and, above all, the elimination of local unemployment within six months of the Anschluss all created a psychological euphoria affecting every class of society, including the workers.”

Advertisement

But, the economic reasons aside, National Socialism was popular because of Hitler’s persecution of the Jews. Ever since the beginning of the century Linz was well known for its anti-Semitism, which was propagated by nationalist organizations, encouraged by local church leaders, and shared by people of all classes and parties, not excluding the Social Democrats. The Nazi seizure of power in Linz began—“quite appropriately,” Mr. Bukey writes—with a savage pogrom and, even before Hitler had arrived in the city on March 12, plans had been made for its “cleansing.” This was carried out with such brutal thoroughness that eight months later on Reichskrystallnacht, November 10, 1938, local storm troopers could find no Jewish property left to plunder or expropriate, except the synagogue, which they burned to the ground as a matter of routine. All but a handful of the area’s Jewish population had by that time been driven from their homes. The remnant, roughly three hundred persons, suffered daily humiliation and harassment until the middle of 1942, when they were deported to the ovens in Poland.

Thanks to the Big Three’s exculpatory statement at Moscow in 1943, these things could now be forgotten. There was no need in postwar Austria for the painful process that, on the other side of the Inn River, was called Vergangenheitsbewältigung (“coming to terms with the past”). There was, apparently, no past to be assimilated; it had simply been expunged, and it was considered to be the worst of bad form even to mention it. Even Bruno Kreisky, federal chancellor of Austria from 1970 to 1983, who, as a partly Jewish socialist, seemed the symbol of the new Austria, lent himself to this conspiracy of silence. When awkward historical facts were alluded to, he was, according to the German news weekly Der Spiegel, wont to say with asperity, “Whenever grass has finally grown over something, along comes some camel or other and eats it all off again!”

That the camels have been grazing in herds since the spring of this year is the fault of Kreisky’s former friend, the sometime diplomat and secretary general of the United Nations, Kurt Waldheim. The discovery, during his ultimately successful campaign for the presidency of the Austrian republic, that he had for years been concealing the truth about his military service during World War II and that, instead of spending the greater part of that conflict as a student in Vienna, as he claimed, he had been in the Balkans as a staff officer with German army units that committed atrocities, caused a sensation and inevitably led to a lively discussion in the international press that went far beyond the Waldheim case to deal with Austrian wartime collaboration in general and to recall to public attention the activities of such notorious countrymen of Waldheim as Adolf Eichmann, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, the head of Hitler’s security police, and Odilo Globocnik, organizer of the extermination of the Jews in the Lublin area. Meanwhile, the reaction of Waldheim’s supporters to new reports about their candidate’s Balkan service was so defiant, xenophobic, and ultimately anti-Semitic in tone that it was hard to avoid the conclusion that it was caused less by resentment over the rigorous scrutiny to which Waldheim’s personal history was being subjected than by a deep disquiet and defensiveness about the nation’s own Nazi past.

In digging out the details of Waldheim’s military career, the World Jewish Congress has provided the most energetic group of researchers (which explains the pointed attacks upon it in the less responsible section of the Austrian press), and its interim report of June 2, which presents an up-to-date summary of their findings, is an impressive and disturbing document. On the basis of captured German files, the WJC team has laboriously reconstructed the record of Waldheim’s various Balkan assignments and analyzed the nature and extent of his responsibilities in each post. Its findings indicate that, after a short medical leave to enable him to recover from a shrapnel wound in the leg that he had suffered on the eastern front toward the end of 1941, he served from March to November 1942 on the command staffs of the Bader Combat Group and its successor, the West Bosnian Combat Group, at Pljevlja, Yugoslavia; from March to July 1943 on the staff of General Alexander Loehr’s Army Group E at Arsakli, Greece, and Podgorica, Yugoslavia; from July to October 1943 as liaison officer with the Italian Eleventh Army in Athens; and from December 1943 until the end of 1944 at Army Group E’s headquarters at Arsakli again—all periods, incidentally, during which, by his own account, he was back in Vienna working on his doctoral dissertation.

Advertisement

His functions were various, ranging from interpreting and transmitting orders to combat units to such activities as interrogation of prisoners, intelligence gathering and analysis, and the briefing of his superiors, and his responsibilities and authority seem to have increased from post to post. His role in the antipartisan operations of the Bader and West Bosnian combat groups in the Kozara Planina mountain range, during which many unarmed civilians were killed and more than 68,000 persons were deported to concentration camps, was prominent enough to win him the King Zvonimir medal of the Nazi puppet government of Croatia. During his first hitch in Arsakli, more than 40,000 Jews, about one fifth of the population of Salonika, were dispatched in Wehrmacht freight cars to Auschwitz, although Waldheim has stated that he neither knew of nor had anything to do with this.

Photographs show that, while he was at Podgorica, he attended staff strategy sessions for implementing Operation Black, a brutal and effective sweep against partisans in Montenegro. Notations in the daily war book that he kept in Athens indicate his knowledge and transmission of orders for the killing of “bandits” captured in battle and the deportation of male civilians. His intelligence work on enemy movements throughout Army Group E’s area of responsibility in Greece was an important factor in determining its plans, and the WJC report presents evidence to show that there was a close correlation between his reports on partisan activity and the devastating reprisal measures by German forces at Iráklion, Stip, and Kocane in August 1944.

On the basis of this record, can one describe Kurt Waldheim as a war criminal? It is entirely understandable that the Yugoslav War Crimes Commission should have done so in 1947; one may surmise that its list was fairly indiscriminate and included a high percentage of the German officers known to have served in the Balkans. It is impossible to say how rigorous the United Nations War Crime Commission’s review of the Yugoslav evidence was before it placed Waldheim’s name on its list of suspected war criminals in 1948 or whether the US Army conducted an independent investigation before putting it on its own wanted list later in the year. Nor has it been made clear just what information about Waldheim’s Nazi past was taken into account by the nations, including the US and the USSR, that supported his candidacy for secretary general of the United Nations in 1971.

More recently, in April of this year, Mr. Waldheim’s predecessor as president of Austria, Rudolf Kirchschläger, reviewed the United Nations file and other documents submitted to him by the WJC and concluded that they would not support prosecution on war-crimes charges, although he added that, despite Mr. Waldheim’s disclaimers, he must have known about the reprisals against the partisans. “What conclusions you draw for the presidential election,” Mr. Kirchschläger told the Austrian people in his television report, “must be left to you.” This is obviously not good enough for the WJC, which insists that the evidence already at hand warrants a thorough investigation by the Austrian government to determine the extent of Mr. Waldheim’s complicity in Nazi atrocities.

One of the most puzzling aspects of the case is why Mr. Waldheim tried to obscure the truth about three years of his life and why, when the real picture began to emerge, he didn’t make a clean breast of things. Even his friends must have been dismayed by the way in which he clung stubbornly to his original story, admitting, as a German reporter pointed out, “at every stage only what could be proved against him” and, even then, depreciating the importance of his admission. The WJC report quotes Allan A. Ryan, Jr., former director of the US Justice Department’s Office of Special Investigations, as saying, “What has disturbed me…are Waldheim’s responses to the allegations against him. The pattern is startlingly similar to those of dozens of Nazi criminals that the Justice Department has prosecuted in the last halfdozen years”—a pattern, the WJC report adds, marked by such things as “the flat and false denial,” “the wrong placewrong time disclaimer,” “the claim that appearance was not reality,” naive professions of ignorance of well-known events, and dismissal of evidence on the grounds that it is merely part of a campaign of slander. In his television speech, President Kirchschläger intimated that many Austrians would find it difficult to forget Mr. Waldheim’s twistings and turnings, and, indeed, public recollection of this behavior will be heavy ballast with which to begin his presidential flight.

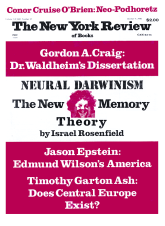

Not much has been written during this confused affair about Mr. Waldheim’s doctoral dissertation, which is perhaps understandable because, as dissertations go, it is not very impressive. Before his life story was so radically corrected, Mr. Waldheim claimed that he had worked on it from the early part of 1942 until its acceptance late in 1944 and that, during this time, he had to overcome problems caused by the wartime dispersion of library holdings, which made it difficult for him to find the books and documents that he needed. But the completed dissertation, which is entitled The Idea of the Reich in Konstantin Frantz, cites no documentary materials and, aside from the books and pamphlets of its subject, lists only ten secondary works as sources, only two of which are mentioned in the footnotes. This and the work’s brevity (ninety-four typescript pages), and the fact that it is a summary rather than an analysis of Frantz’s thought and lacks any comparative dimension, indicate that it was a rush job, largely accomplished, in all probability, during the three months of leave that followed Waldheim’s service in Bosnia.

Even so, it is not uninteresting. Konstantin Frantz was an independent and outspoken German publicist who, at the height of the national enthusiasm over Bismarck’s unification of Germany in 1987, rejected the new creation on the grounds that it had been constituted in such a way as to deprive Germany of the psychological conditions for healthy development. Surely, he wrote, a land

containing as many different elements as Germany, a country entwined with its neighbors on all sides and bordering on six different nationalities, a country that has experienced a history comparable to no other in respect both of the variety of political forms created and the intrinsic importance of its events, must necessarily have achieved a constitution peculiar to itself.

Instead, Germany had had imposed upon it a narrow national framework and a constitution based on foreign models, which would encourage the spread of liberalism, individualism, materialism, and socialism, all destructive of the age-old German sense of community.

Germany’s true destiny, Frantz wrote, lay in the creation of a new Reich, the philosophical basis of which would be a political-religious-ethical federalism that reconciled freedom with community, diversity with common purpose, and historical continuity with the demands of the present, and whose political foundation would be a Bund comprising the lands that had belonged to the Holy Roman Empire, joined together with a wider union that would include the eastern provinces of Prussia and the Austrian Empire and, in due course, Switzerland and the Low Countries. This Reich would be animated by the old German mission in the east: the duty of protecting Western civilization by colonizing the Slav lands and erecting a barrier against the threat of Russia. But beyond that it must strive to break out into the Atlantic by way of the North Sea ports and, through the destruction of the Turkish Empire, to extend its influence to the Black Sea.

These, however, were remote tasks. The immediate objective was to create a Reich in central Europe that would transcend national perspectives and limitations, a Völkergemeinschaft (“community of peoples”) in which the great and small would have common political and cultural purposes, but in which the German core, animated by an “idealistic Realpolitik,” would be “the carrier and vital center of European development,” and the guarantor of international peace. Frantz was, in short, a curious combination of system-builder and imperialist, torn between his belief in the ability of federal systems to alleviate the friction and conflict of contemporary international relations and the vision of a new German Weltpolitik more grandiose than that propounded earlier by Friedrich List.

All of this Kurt Waldheim spread forth in his dissertation, without accompanying his exposition with any critical comment of his own. The WJC report has quoted a reference in the dissertation’s conclusion to “the current great conflict of the Reich with the non-European world” and the “magnificent collaboration of all the peoples of Europe under the leadership of the Reich…against the danger from the east,” presumably as evidence of the intensity of Waldheim’s pro-Nazi sentiments. But the reference to these events, which Waldheim mildly says shows the continued relevance of Frantz’s writings, was the sort of thing that was surely common and expected in dissertations submitted to a Nazified university in the middle of the war, and it was probably, in any case, intended, in case he was one of the dissertation’s readers, to please Heinrich Ritter von Srbik, the reigning star among Austrian historians at that time and the promoter of a new historiography based upon the Reichsidee, which he believed was being realized in the policy of Adolf Hitler.

In this connection, it is what Waldheim excluded from his dissertation that is intriguing. Konstantin Frantz was a rabid anti-Semite, who expressed his outrage over the fact that Berlin was the capital of the German Empire by writing:

If a visitor to the baths in Reichenhall could scribble on the wall Gott! wie schön ist’s doch hienieden./ Wo man hinspuckt—lauter Jüden,1 so could any visitor to the imperial capital write the same in his diary.

In his book on federalism, Frantz argued that the Jews represented the most serious threat to the political and economic stability and the moral integrity of the Western world and that the first task of the new Reich must be to solve the Jewish question. How this was to be done, he did not spell out in any detail, although he did say that an indispensable first step would be a reversal of the process of emancipation and the revocation of all legislation that had assured Jews of civil equality and that, in effecting this, one must dispense with “all talk of humanity and enlightenment.”

Although his dissertation was in large part an exposition of the contents of Frantz’s Der Föderalismus, Waldheim did not mention any of its anti-Semitic arguments, although he might have commended himself to some of his readers by doing so. We can only speculate about his reasons, but it is not impossible (why not give him the benefit of the doubt?) that he found those parts of Frantz’s work both distasteful and irrational, whereas, on the other hand, he was fascinated, as the second part of his dissertation shows, by what Frantz had to say about the possibility of a federal political structure creating not only new forms of law but a new international consciousness.

If there is anything in this, then we may detect a tenuous connection between Waldheim’s dissertation and his memoir In the Eye of the Storm, which is largely an account of his ten years as secretary general of the United Nations. Here he describes the attempts of an imperfect and often maligned federal system, formed, as he writes, “when the peoples and governments of the world, still reeling from the shock of World War II, were…prepared to yield up certain parts of their sovereignty in favor of an international organization,” to extend the recognition of law and the consciousness of community in a world endangered by the hypernationalism of the former colonial nations and the doom-laden rivalry of the weapons-obsessed superpowers. Something of Konstantin Frantz’s idea of the centrality of the Völkergemeinschaft echoes in Waldheim’s reminder that “the Charter of the United Nations specifically talks of ‘people’ and not of governments…. More clearly than ever before, the people—regardless of frontiers—will have to make it clear that they do not want preparations for war but designs for peace.”

In the Eye of the Storm is an intelligent and informative book and, in its criticism of American attitudes toward the United Nations and of the Reagan administration’s decision to leave UNESCO, persuasive. But in view of the revelations made during Waldheim’s campaign for the Austrian presidency, what may be most striking to its readers is the persistent deficiency of its author’s memory, here evidenced not only in the absence from his account of his early life of any reference to his military service in the Balkans, but in his failure to mention that, when he was foreign minister during the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, he ordered his envoy in Prague to close the Austrian mission to Czech subjects seeking asylum and to expel those already in the building, although this order was contrary to previous practice and was, for that reason, disobeyed. Whether Waldheim’s behavior on this occasion was prompted by a desire to forestall embarrassing Soviet disclosures about earlier activities on his part and whether it assured him, later on, of Soviet support for his candidacy of the secretary general’s post (which was given promptly and almost insistently) are intriguing questions but must remain conjectural.

Meanwhile, Kurt Waldheim has gone on to greater things, although there may be problems ahead. In April, the US Department of Justice’s Office of Special Prosecutions recommended to Attorney General Edwin Meese III that he be barred permanently from this country on the basis of a federal statute that applies to persons who, in association with the Nazi government of Germany, persecuted others. This may be an augury of trouble for Austria’s future relations with other states, although Shimon Peres was probably right in saying recently, “Austria’s problem is its relations with itself.”

This Issue

October 9, 1986

-

*

God! how beautiful the view! Where e’er you chance to spit—a Jew! ↩