Adults who want to have sex with children sometimes look for jobs that will make it easy. They want authority over kids, but no very onerous supervision; they also want positions that will make them seem more trustworthy than their potential accusers. Such considerations have infamously led quite a few pedophiles to sully the priesthood over the years, but the priesthood isn’t for everyone. For some people, moral authority comes less naturally than blunter, more violent kinds.

Ray Brookins worked for the Texas Youth Commission (TYC), the state’s juvenile detention agency. In October 2003, he was hired as head of security at the West Texas State School in Pyote. Like most TYC facilities, it’s a remote place. The land is flat to the horizon, scattered with slowly bobbing oil derricks, and always windy. It’s a long way from the families of most kids confined there, who tend to be urban and poor; a long way from any social services, or even the police. It must have seemed perfect to Brookins—and also to John Paul Hernandez, who was hired as the school’s principal around the same time. Almost immediately, Brookins started pulling students out of their dorms at night, long after curfew, and bringing them to the administration building. When asked why, he said it was for cleaning.1

In fact, according to official charges, for sixteen months Brookins and Hernandez molested the children in their care: in offices and conference rooms, in dorms and darkened broom closets and, at night, out in the desert. The boys tried to tell members of the staff they trusted; they also tried, both by letter and through the school’s grievance system, to tell TYC officials in Austin. They did so knowing that they might be retaliated against physically, and worse, knowing that if Brookins caught them complaining he could and would extend their confinement,2 and keep on abusing them.3 They did so because they were desperate. But they were ignored by the authorities who should have intervened: both those running the school and those running the Texas Youth Commission.4 Nor did other officials of the TYC who were informed by school staff about molestation take action.

Finally, in late February 2005, a few of the boys approached a volunteer math tutor named Marc Slattery. Something “icky” was going on, they said. Slattery knew it would be futile to go to school authorities—his parents, also volunteers, had previously told the superintendent of their own suspicions, and were “brow beat” for making allegations without proof5—so the next morning he called the Texas Rangers.6 A sergeant named Brian Burzynski made the ninety-minute drive from his office in Fort Stockton that afternoon. “I saw kids with fear in their eyes,” he testified later, “kids who knew they were trapped in an institution where the system would not respond to their cries for help.”7

Slattery had only reported complaints against Brookins, not against Hernandez, but talking to the boys, Burzynski quickly realized that the principal was also a suspect. (Hernandez, it seems, was less of a bully than Brookins. When a boy resisted Brookins’s advances in 2004, he was shackled in an isolation cell for thirteen hours.8 Hernandez preferred to cajole students into sex with offers of chocolate cake, or help getting into college, or a place to stay after they were released.9) The two men were suspended and their homes searched—at which point it was discovered that Brookins was living on school grounds with a sixteen-year-old, who was keeping some of Brookins’s “vast quantity of pornographic materials” under his bed.10 Suspected semen samples were taken from the carpet, furniture, and walls of Brookins’s office. He quickly resigned. In April, Hernandez was told he would be fired, whereupon he too resigned.

When the TYC received Burzynski’s findings, it launched its own investigation. The internal report this produced was deeply flawed. Investigators didn’t interview or blame senior administrators in Austin, though many of them had seen the warning signs and explicit claims of abuse at Pyote. But agency officials saw how damning the story was. Neither their report nor Burzynski’s was made public.11

The Rangers forwarded Burzynski’s report to Randall Reynolds, the local district attorney, but he did nothing. Even though it’s a crime in all fifty states for corrections staff to have sex with inmates of any age, prosecutors rarely bring charges in such cases. For a time, from the TYC’s perspective, the problem seemed to go away. The agency suspended Lemuel “Chip” Harrison, the superintendent of the school, for ninety days after concluding its investigation—he had ignored complaints about Brookins and Hernandez from many members of the staff—but then it promoted him, making him director of juvenile corrections. Brookins found a job at a hotel in Austin, and Hernandez, astonishingly, became principal of a charter school in Midland.

Advertisement

Rumors have a way of spreading, though, however slowly. Eventually some reporters started digging, and on February 16, 2007, Nate Blakeslee broke the story in The Texas Observer. Doug Swanson followed three days later in The Dallas Morning News, starting an extraordinary run of investigative reporting in that paper: forty articles on abuse and mismanagement in the TYC by the end of March 2007, and to date more than seventy.12 Pyote was only the beginning. The TYC’s culture was thoroughly corrupt: rot had spread to all thirteen of its facilities.

Since January 2000, it turned out, juvenile inmates had filed more than 750 complaints of sexual misconduct by staff. Even that number was generally thought to underrepresent the true extent of such abuse, because most children were too afraid to report it: TYC staff commonly had their favorite inmates beat up those who complained. And even when they did file grievances, the kids knew it was unlikely to do them much good. Reports were frequently sabotaged, evidence routinely destroyed.13

In the same six-year period, ninety-two TYC staff had been disciplined or fired for sexual contact with inmates, which can be a felony. (One wonders just how blatant they must have been.) But again, as children’s advocate Isela Gutierrez put it, “local prosecutors don’t consider these kids to be their constituents.”14 Although five of the ninety-two were “convicted of lesser charges related to sexual misconduct,” all received probation or had their cases deferred. Not one agency employee in those six years was sent to prison for sexually abusing a confined child.15 And despite fierce public outrage at the scandal, neither Brookins nor Hernandez has yet faced trial. In the face of overwhelming evidence, but with recent history making their convictions unlikely, both claim innocence.

Texas is hardly the only state with a troubled juvenile justice system. In 2004, the Department of Justice investigated a facility in Plainfield, Indiana, where kids sexually abused each other so often and in such numbers that staff created flow charts to track the incidents. The victims were frequently as young as twelve or thirteen; investigators found “youths weighing under seventy pounds who engaged in sexual acts with youths who weighed as much as 100 pounds more than them.”16 A youth probation officer in Oregon was arrested the same year on more than seventy counts of sex crimes against children, and one of his victims hanged himself.17 In Florida in 2005, corrections officers housed a severely disabled fifteen-year-old boy whose IQ was 32 with a seventeen-year-old sex offender, giving the seventeen-year-old the job of bathing him and changing his diaper. Instead, the seventeen-year-old raped him repeatedly.18

The list of such stories goes on and on. After each of them was made public, it was possible for officials to contend that they reflected anomalous failings of a particular facility or system. But a report just issued on January 7 by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) should change that. Mandated by the Prison Rape Elimination Act of 2003 (PREA), and easily the largest and most authoritative study of the issue ever conducted, it makes clear that the crisis of sexual abuse in juvenile detention is nationwide.

Across the country, 12.1 percent of kids questioned in the BJS survey said that they’d been sexually abused at their current facility during the preceding year. That’s nearly one in eight, or approximately 3,220, out of the 26,550 who were eligible to participate. The survey, however, was only given at large facilities that held young people who had been “adjudicated”—i.e., found by a court to have committed an offense—for at least ninety days, which is more restrictive than it may sound. In total, according to the most recent data, there are nearly 93,000 kids in juvenile detention on any given day.19 Although we can’t assume that 12.1 percent of the larger number were sexually abused—many kids not covered by the survey are held for short periods of time, or in small facilities where rates of abuse are somewhat lower—we can say confidently that the BJS’s 3,220 figure represents only a small fraction of the children sexually abused in detention every year.

What sort of kids get locked up in the first place? Only 34 percent of those in juvenile detention are there for violent crimes. (More than 200,000 youth are also tried as adults in the US every year, and on any given day approximately 8,500 kids under eighteen are confined in adult prisons and jails. Although probably at greater risk of sexual abuse than any other detained population, they haven’t yet been surveyed by the BJS.) According to the National Prison Rape Elimination Commission, which was itself created by PREA, more than 20 percent of those in juvenile detention were confined for technical offenses such as violating probation, or for “status offenses” like missing curfews, truancy, or running away—often from violence and abuse at home. (“These kids have been raped their whole lives,” said a former officer from the TYC’s Brownwood unit.20) Many suffer from mental illness, substance abuse, and learning disabilities.

Advertisement

Fully 80 percent of the sexual abuse reported in the study was committed not by other inmates but by staff. And surprisingly, 95 percent of the youth making such allegations said that they were victimized by female staff. Sixty-four percent of them reported at least one incident of sexual contact with staff in which no force or explicit coercion was used. Staff caught having sex with inmates often claim it’s consensual. But staff have enormous control over inmates’ lives. They can give inmates privileges, such as extra food or clothing or the opportunity to wash, and they can punish them: everything from beatings to solitary confinement to extended detention. The notion of a truly consensual relationship in such circumstances is grotesque even when the inmate is not a child.

Nationally, however, fewer than half of the corrections officials whose sexual abuse of juveniles is confirmed are referred for prosecution, and almost none are seriously punished. A quarter of all known staff predators in state youth facilities are allowed to keep their positions.21

The biggest risk factor found in the study was prior abuse. Some 65 percent of kids who had been sexually assaulted at another corrections facility were also assaulted at their current one. In prison culture, even in juvenile detention, after an inmate is raped for the first time he is considered “turned out,” and fair game for further abuse.22 Eighty-one percent of juveniles sexually abused by other inmates were victimized more than once, and 32 percent more than ten times. Forty-two percent were assaulted by more than one person. Of those victimized by staff, 88 percent had been abused repeatedly, 27 percent more than ten times, and 33 percent by more than one facility employee. Those who responded to the survey had been in their facilities for an average of 6.3 months.

Just as the BJS report on sexual abuse in juvenile detention facilities shows that problems like the ones at Pyote aren’t limited to Texas, two previous BJS reports, on the incidence of sexual abuse in adult prisons and jails, show that abuses in juvenile detention are only a small part of a much larger human rights problem in this country. Published in December 2007 and June 2008, these were extensive studies: they surveyed a combined total of 63,817 inmates in 392 different facilities.

Sexual abuse in detention is difficult to measure. Prisoners sometimes make false allegations, but sometimes, knowing that true confidentiality is almost nonexistent behind bars and fearing retaliation, they decide not to disclose abuse. Although those who responded to the BJS surveys remained anonymous, it seems likely, on balance, that the studies underestimate the incidence of prisoner rape.23 But even taken at face value, they reveal much more systemic abuse than has been generally recognized or admitted.

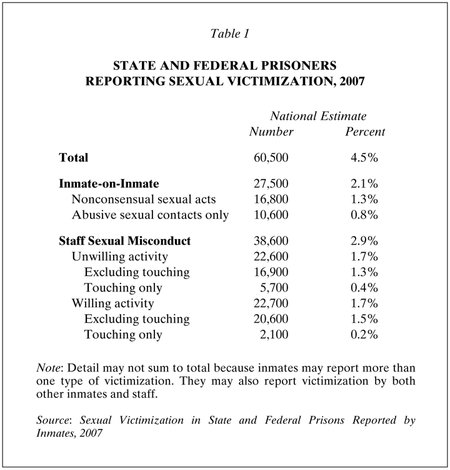

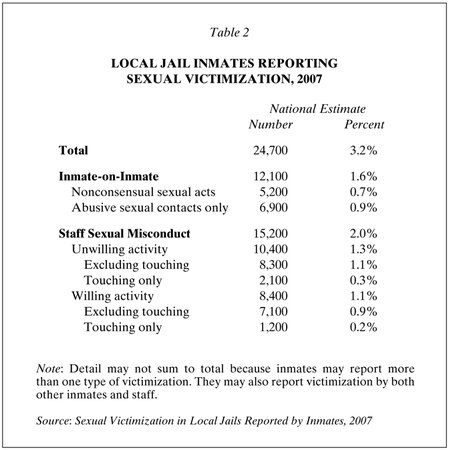

Using a snapshot technique—surveying a random sample24 of those incarcerated on a given day and then extrapolating only from those numbers—the BJS found that 4.5 percent of the nation’s prisoners, i.e., inmates who have been convicted of felonies and sentenced to more than a year, had been sexually abused in the facilities at which they answered the questionnaire during the preceding year: approximately 60,500 people. Moreover, 3.2 percent of jail inmates—i.e., people who were awaiting trial or serving short sentences—had been sexually abused in their facilities over the preceding six months, meaning an estimated total, out of those jailed on the day of the survey, of 24,700 nationwide.25

Both studies divide these reports of abuse in two different ways. They ask whether the perpetrator was another inmate or one of the facility’s staff. And they differentiate between willing and unwilling sexual contact with staff, although recognizing that it is always illegal for staff to have sex with inmates. Similarly, they distinguish between “abusive sexual contact” from other inmates, or unwanted sexual touching, and what most people would call rape. The results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Overall, the more severe forms of abuse outnumber the lesser ones in both surveys. And the reported perpetrators in both jails and prisons, as in juvenile detention, are more often staff than inmates.

The prison survey estimates not only the number of people abused, but the instances of abuse. In our opinion, the BJS’s methodology here undercounts the true number. Inmates who said they had been sexually abused were asked how many times. Their options were 1, 2, 3–10, and 11 times or more; that answers of “3–10” were assigned a value of 5, and “11 or more” a value of 12. We know of no reason to think that answers of “3–10” should be skewed so far toward the low end of the range, however—and inmates are sometimes raped many more than twelve times. Bryson Martel, for example:

When I went to prison, I was twenty-eight years old, I weighed 123 pounds, and I was scared to death…. [Later] I had to list all the inmates who sexually assaulted me, and I came up with 27 names. Sometimes just one inmate assaulted me, and sometimes they attacked me in groups. It went on almost every day for the nine months I spent in that facility.

Because of these attacks, Martel contracted HIV. “You never heal emotionally,” he said.26

Methodology aside, though, this question about frequency was an important one to ask, precisely because rape in prison is so often serial, and so often gang rape.27 The BJS estimates that there were 165,400 instances of sexual abuse in state and federal prisons over the period of its study, an average of about two and a half for every victim. Had it made a similar estimate on the basis of data from its youth study using the same method, it would have found that juvenile victims were abused an average of six times each. Especially when thinking about the effects on a child, it’s awful to realize that these numbers are probably too low.

What little attention the BJS reports on adult victims have received in the press has so far mostly been devoted to the prison study, not the one on jails. On June 23, 2009, the day the National Prison Rape Elimination Commission released its report, both The New York Times and The Washington Post ran editorials praising it, and both referred to the 60,500 number as if that represented the yearly national total for all inmates.28 However, we believe that these papers missed the true implication of the BJS reports, and that the jail study is the more important of the two.

This is partly because the study of jails answers more questions, and does more to help us understand the dynamics of sexual abuse in detention—beginning with the racial dynamics.29 Of white jail inmates, 1.8 percent reported sexual abuse by another inmate, whereas 1.3 percent of black inmates did. But when considering staff-on-inmate abuse, the situation is reversed. 1.5 percent of white inmates reported such incidents, but 2.1 percent of black inmates did. Overall, a black inmate is more likely to suffer sexual abuse in detention than a white one, 3.2 percent to 2.9 percent. The study did not report the race of perpetrators.30

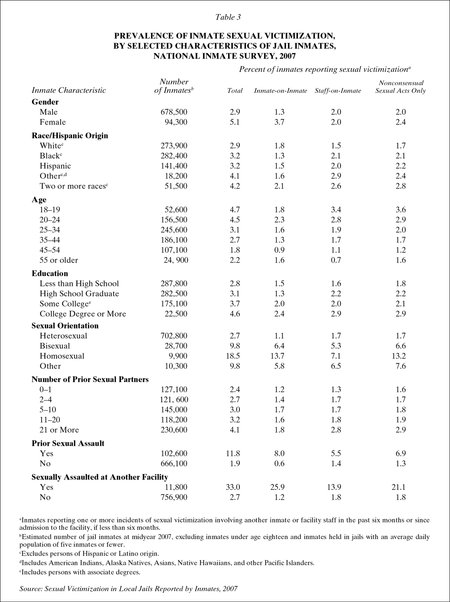

Advocates have long known that victims of sexual abuse in detention tend to be those perceived as unable to defend themselves, and the jail study confirms this. Women were more likely to report abuse than men.31 Younger inmates are more likely to be abused than older ones, gay inmates much more than straight ones, and people who had been abused at a previous facility most of all. (See Table 3 for more detail.) Those targeted for abuse are also likely to be vulnerable in ways the BJS did not address in this report. Often they have mental disabilities or mental illness,32 they are disproportionately likely to be first-time and nonviolent offenders,33 and most simply, they are likely to be small.34

Nearly 62 percent of all reported incidents of staff sexual misconduct involved female staff and male inmates. Female staff were involved in 48 percent of staff-on-inmate abuse in which the inmates were unwilling participants. The rates at which female staff seem to abuse male inmates, in jails and in juvenile detention, clearly warrant further study. Of the women in jail, 3.7 percent reported inmate-on-inmate sexual abuse; 1.3 percent of men did. Does this mean that women are more likely to abuse each other behind bars than men, or that they’re more willing to admit abuse? We don’t know—but if they’re simply more willing to admit abuse, then the BJS findings on men may have to be multiplied dramatically.

There is another, starker reason why the jail study is the most important. Jail is where most inmates get raped. On first glance at the reports it doesn’t look this way. But—and this is what the press seems to have missed—because the BJS numbers come from snapshot surveys, they represent only a fraction of those incarcerated every year. People move in and out of jail very quickly. The number of annual jail admissions is approximately seventeen times higher than the jail population on any given day.35

To get the real number of those sexually abused in jails over the course of a year, however, we can’t simply multiply 24,700 by seventeen. Many people go to jail repeatedly over the course of a year; the number of people who go to jail every year is quite different from the number of admissions. Surprisingly, no official statistics are kept on the number of people jailed annually.36 We’ve heard a very well-informed but off-the-record estimate that it is approximately nine times as large as the daily jail population, but we can’t yet be confident about that.

Even if we could, though, we still couldn’t just multiply 24,700 by nine. Further complicating the matter, snapshot techniques like the BJS’s will disproportionately count those with longer sentences. If Joe is jailed for one week and Bill for two, Bill is twice as likely to be in jail on the day of the survey. Presumably, the longer you spend in jail, the more chance you have of being raped there. But even that is not as simple as it seems. Because those raped behind bars tend to fit such an identifiable profile—to be young, small, mentally ill, etc.—they are quickly recognized as potential victims. Very likely, they will be raped soon after the gate closes behind them, and repeatedly after that. The chance of being raped after a week in jail is likely not so different from the chance of being raped after a month. Probably more significant (at least, statistically) is the difference in the number of times an inmate is likely to be raped.

What is the right multiple—are five, six, seven times 24,700 people molested and raped in jail every year? We don’t know yet, but we hope to soon. PREA requires the BJS to conduct its surveys annually. The BJS has revised its questionnaire to ask those who report abuse how long after they were jailed the first incident took place; it is also collecting data on the number of people jailed every year and the lengths of time they serve. Together, this new information should lead to much better estimates.

We do know already that all the BJS numbers published so far, which add up to almost 90,000, represent only a small portion of those sexually abused in detention every year. And that is without even considering immigration detention, or our vast system of halfway houses, rehab centers, and other community corrections facilities. Nor does it include Native American tribal detention facilities operated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs or corrections facilities in the territories.

In 1994, in Farmer v. Brennan, the Supreme Court angrily declared that “having stripped [inmates] of virtually every means of self-protection and foreclosed their access to outside aid, the government and its officials are not free to let the state of nature take its course.” Rape, wrote Justice David Souter, is “simply not ‘part of the penalty'” we impose in our society.37 But for many hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children, whether they were convicted of felonies or misdemeanors or simply awaiting trial, it has been. Most often, their assailants have been the very agents of the government who were charged with protecting them.

Beyond the physical injuries often sustained during an assault,38 and beyond the devastating, lifelong psychological damage inflicted on survivors, rape in prison spreads diseases, including HIV.39 Of all inmates, 95 percent are eventually released40—more than 1.5 million every year carrying infectious diseases, many of them sexually communicable41—and they carry their trauma and their illnesses with them, back to their families and their communities.

Prisoner rape is one of this country’s most widespread human rights problems, and arguably its most neglected. Frustratingly, heartbreakingly—but also hopefully—if only we had the political will, we could almost completely eliminate it.

In the second part of this essay we will discuss the National Prison Rape Elimination Commission’s report, which analyzes the dynamics and consequences of prisoner rape, shows how sexual abuse can be and in many cases already is being prevented in detention facilities across the country, and proposes standards for its prevention, detection, and response. Those standards are now with US Attorney General Eric Holder, who by law has until June 23, 2010, to review them before issuing them formally, following which they will become nationally binding. We will discuss the attorney general’s troubling review process, the opposition of some corrections officials to the commission’s standards, and why some important corrections leaders are so resistant to change.

—February 10, 2010

This Issue

March 11, 2010

-

1

Nate Blakeslee, “Hidden in Plain Sight,” The Texas Observer, February 23, 2007 (published on the Web on February 16). This was the first story in the press about the troubles at Pyote, and is probably still the single best account of them. ↩

-

2

“At TYC, an inmate’s length of stay is determined by a complex and controversial program known as Resocialization,…[which] is composed of specific academic, behavioral, and therapeutic objectives. Each category has numbered steps, known as phases, that the offender must reach…. Inmates have complained that TYC guards often retaliate against them by lodging disciplinary actions that cause phase setbacks.” (Holly Becka and Gregg Jones, “Length of Stay Fluid for Many TYC Inmates,” The Dallas Morning News, March 24, 2007.) At Pyote, more advanced phases also meant greater privileges: access to “hygiene items,” for example (Burzynski, Report of Investigation, p. 52). ↩

-

3

After Burzynski began his investigation, the school superintendent determined that at least 25 students had been kept at the facility without adequate cause. (Report of Investigation, p. 63). Brookins also seems to have pursued at least one student after his release from juvenile detention. (Report of Investigation, pp. 73–74.) ↩

-

4

Nate Blakeslee, “New Evidence of Altered Documents in TYC Coverup,” The Texas Observer, March 11, 2007. See also Blakeslee, “Hidden in Plain Sight.” ↩

-

5

Tish Elliott-Wilkins, Summary Report for Administrative Review, p. 6. ↩

-

6

The Texas Rangers Division is a law enforcement agency with statewide jurisdiction; typically, Rangers become involved in cases that local authorities are unwilling or unable to handle properly. ↩

-

7

Emily Ramshaw, “Lawmakers Lambaste TYC Board for Failing to Act,” The Dallas Morning News, March 8, 2007. ↩

-

8

Burzynski, Report on Investigation, p. 7. TYC policy states that when students are placed in shackles, administrators must reiterate their approval every thirty minutes; Brookins, however, “told security staff not to bother him about the situation until the next morning.” ↩

-

9

Burzynski, Report on Investigation, pp. 32 and 36. ↩

-

10

“Accused TYC Official Lived with Boy,” The Dallas Morning News, March 8, 2007. Both Brookins and the boy denied that they were having a sexual relationship. ↩

-

11

The TYC did, however, send a copy of the report to its board of directors; and it later turned out that Governor Rick Perry’s office had been warned about sexual abuse in the TYC by multiple sources. See Ramshaw, “Lawmakers Lambaste TYC Board for Failing to Act”; Nate Blakeslee, “Sins of Commission,” Texas Monthly, May 2007; and Doug J. Swanson and Steve McGonigle, “Mistakes, Mismanagement Wrecked TYC,” The Dallas Morning News, May 13, 2007. ↩

-

12

For an index of these, see www.shron.wordpress.com/texas-youth-commission-scandal/. The paper also put a number of video interviews on its Web site, available at www.dallasnews.com/s/dws/photography/2007/tyc/. ↩

-

13

See Gregg Jones, Holly Becka, and Doug J. Swanson, “TYC Facilities Ruled by Fear,” The Dallas Morning News, March 18, 2007: ↩

-

14

See Blakeslee, “Hidden in Plain Sight.” ↩

-

15

See Doug J. Swanson, “Sex Abuse Reported at Youth Jail,” The Dallas Morning News, February 18, 2007. ↩

-

16

See Bradley J. Schlozman, “Letter to Mitch Daniels, Governor, Indiana, Regarding Investigation of the Plainfield Juvenile Correctional Facility, Indiana,” September 9, 2005, available at www.justice.gov/crt/split/documents/split_indiana_plainfield_juv_findlet _9-9-05.pdf. ↩

-

17

See “Teens’ Abuser Gets Locked Up for Life,” The Oregonian, October 14, 2005. ↩

-

18

See “Herald Watchdog: Juvenile Justice: State Put Disabled Boy in Sex Offender’s Care,” Miami Herald, October 20, 2005. ↩

- 19

-

20

See Doug J. Swanson, “Sex Abuse Alleged at 2nd Youth Jail,” The Dallas Morning News, March 2, 2007. The article goes on to say that most inmates in Texas juvenile facilities “don’t have criminal records because they are adjudicated as delinquent in a civil hearing and committed to TYC for open-ended periods…. About 60 percent of them come from low-income homes. More than half have families with criminal histories, and 36 percent had a childhood history of abuse or neglect. Some 80 percent have IQs below the mean score of 100.” ↩

-

21

See “Sexual Violence Reported by Juvenile Correctional Authorities, 2005–06,” Bureau of Justice Statistics, available at www.bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/svrjca0506.pdf. ↩

-

22

See National Prison Rape Elimination Commission Report, p. 71. ↩

-

23

This opinion is shared by the National Prison Rape Elimination Commission: see its report, pp. 1, 39, and 40. The commissioners were commenting on adults, but children may be even more likely to underreport abuse. ↩

-

24

In the prison study, however, “the size measures for [state] facilities housing female inmates were doubled to ensure a sufficient number of women to allow for meaningful analyses of sexual victimization by gender.” And inmates younger than 18 were excluded from the surveys of adult facilities. ↩

-

25

Prison inmates had been in their current facilities for an average of 8.5 months prior to taking the survey; jail inmates had been in theirs for an average of 2.6 months. ↩

-

26

See www.justdetention.org/en/action updates/AU1009_web.pdf. ↩

-

27

According to the jail study, 20 percent of incidents of staff-on-inmate sexual abuse involved more than one perpetrator, and 33 percent of inmate-on-inmate incidents did. ↩

-

28

“Rape in Prison,” TheNew York Times, June 23, 2009, and “A Prison Nightmare: A Federal Commission Offers Useful Standards for Preventing Sexual Abuse Behind Bars,” The Washington Post, June 23, 2009. ↩

-

29

It is impossible to understand life behind bars without considering racial dynamics—and above all, the unconscionable demographic composition of those we incarcerate in this country. For more on this, see David Cole’s excellent article in these pages, “Can Our Shameful Prisons Be Reformed?,” The New York Review, November 19, 2009. ↩

-

30

Since some inmates report abuse by other inmates and by staff, the percentages given do not amount to the totals. 3.2 percent of Hispanic inmates reported sexual abuse in jail; of those who said their race was “other,” which includes American Indians, Native Hawaiians, and other Pacific Islanders, 4.1 percent did; and 4.2 percent of inmates who are two or more races (excluding those of Hispanic or Latino origin) reported abuse. ↩

-

31

“The number of incarcerated adult women increased by 757 percent from 1977 to 2007.” (National Prison Rape Elimination Commission Report, p. 44.) And many of these women have been raped before going to prison. In the Washington Corrections Center for Women, for example, “more than 85 percent of women in the facility had reported a history of past sexual abuse.” (Report, p. 63.) “Studies found that from 31 to 59 percent of incarcerated women reported being sexually abused as children, and 23 to 53 percent reported experiencing sexual abuse as adults.” (Report, p. 71.) ↩

-

32

National Prison Rape Elimination Commission Report, p. 7. Robert Dumond, a researcher and clinician who is an expert on sexual abuse in detention, told the commission: ↩

-

33

“More than half of all newly incarcerated individuals between 1985 and 2000 were imprisoned for nonviolent drug or property offenses.” (National Prison Rape Elimination Commission Report, p. 44.) ↩

-

34

See David Kaiser, “A Letter on Rape in Prisons,” The New York Review, May 10, 2007. ↩

-

35

See Todd D. Minton and William J. Sabol, Jail Inmates at Midyear 2007 (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2008), p. 2; available at www.bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/jim07.pdf. Local jails made an estimated 13 million admissions during the twelve months ending June 29, 2007; the jailed inmate population on that day was 780,581. The same logic applies to the prison survey results, but there is much less turnover in the prison population. It also applies, more forcefully, to the results of the juvenile detention survey. ↩

-

36

Neither do there seem to be good statistics on the annual number of admissions to prison. We do know that as of June 30, 2008, counting both prisons and jails, the US incarcerates about 2.4 million people on any given day. (See Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Jail Inmates at Midyear 2008—Statistical Tables,” available at www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/jim08st.pdf. See also Heather C. West and William J. Sabol, Prison Inmates at Midyear 2008—Statistical Tables, Bureau of Justice Statistics, available at www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/contentpub/pdf/pim08st.pdf.) This is more than any other country in the world, either on a per capita basis or in absolute numbers. Including those in immigration and youth detention and those supervised in the community (in halfway houses and rehabilitation centers, on probation or parole), more than 7.3 million people are in the corrections system on any given day. The cost to the country is more than $68 billion every year. (See National Prison Rape Elimination Commission Report, p. 2.) ↩

-

37

Farmer v. Brennan, 511 US 825 (1994). ↩

-

38

According to the jail study, approximately 20 percent of those sexually abused also suffered other physical injuries in the process; approximately 85 percent of that number suffered at least one serious injury, including knife and stab wounds, broken bones, rectal tearing, chipped or knocked-out teeth, internal injuries, and being knocked unconscious. ↩

-

39

“In 2005–2006, 21,980 State and Federal prisoners were HIV positive or living with AIDS. Researchers believe the prevalence of hepatitis C in correctional facilities is dramatically higher, based on [the] number of prisoners with a history of injecting illegal drugs prior to incarceration…. The incidence of HIV in certain populations outside correctional systems is likely attributable in part to [sexual] activity within correctional systems. Because of the disproportionate representation of minority men and women in correctional settings it is likely that the spread of these diseases in confinement will have an even greater impact on minority men, women, and children and their communities.” (National Prison Rape Elimination Commission Report, pp. 129–130). The commissioners seem to be saying here, as delicately as they can, that they suspect prisoner rape has contributed to the way HIV infection in this country has shifted demographically: i.e., to the way AIDS has changed from being a predominantly gay disease to a predominantly black one. ↩

-

40

National Prison Rape Elimination Commission Report, p. 26. ↩

-

41

National Prison Rape Elimination Commission Report, p. 134. ↩