Exhibitions of drawings by Leonardo, almost always based on the uniquely rich collection in the Royal Library at Windsor, are relatively common. But outside the Louvre, which owns four of Leonardo’s pictures, it is rare indeed to have the opportunity of seeing more than a couple of his paintings together. The museums that possess such works are understandably reluctant to loan them, both because of their fragility and because of their fame; and apart from the Louvre, only the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg can make a plausible claim to possess more than one finished picture by him. Yet the exhibition currently at the National Gallery in London includes, according to the sponsor of the exhibition, Credit Suisse, “around half of the 15 or so paintings by Leonardo which are known to be in existence, as well as 50 of his original drawings,” including thirty-three from the Royal Collection. For most of those fortunate enough to have acquired tickets, for which demand vastly exceeds supply, this is an experience that is unlikely to be repeated.

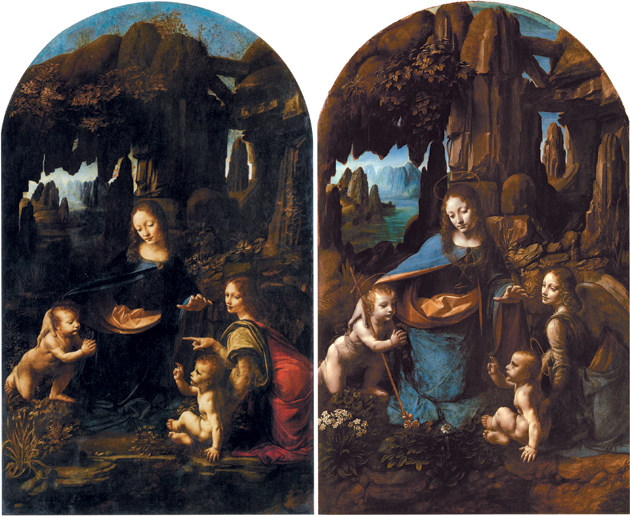

To have brought together such a remarkable group of works is a diplomatic triumph, made possible by the generosity of the Louvre in lending the largest surviving completed work by Leonardo, The Virgin of the Rocks, which, certainly for the first time in centuries and possibly for the first time ever, is shown in the same room as another version that belongs to the National Gallery. The relationship of the two pictures has long been debated, and this exhibition provides an unprecedented opportunity to examine the problem afresh, and to see the pictures in the presence of others produced during the main period of Leonardo’s activity in Milan, between about 1482 and 1499. This was the longest time he spent in any city as an adult, but while he was there he was not working full-time as a painter. The only paintings that he is known to have certainly produced in these years are The Virgin of the Rocks, The Last Supper, now a total ruin, and the Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani—sometimes called The Lady with an Ermine—from Kraków, which is also in the present exhibition, and the decoration for a room (the Sala delle Asse) in the castle of the Sforza in Milan, which is almost entirely repainted.

As the sponsor hinted in the foreword quoted above, although Leonardo is among the most intensively studied of all European artists, the status of many of the pictures most often associated with him, and especially those supposedly painted in Milan, remains highly controversial. In particular, his relationship with several Milanese artists obviously much influenced by him, such as Boltraffio and Ambrogio de Predis, is still not fully understood. Fortunately, the selection of works in the exhibition is notably intelligent, including not just the works by Leonardo most often assigned to the Milanese period, but also paintings by other artists in the city. The usually unsympathetic display area in the basement of the Sainsbury wing has the great advantage of permitting very precise adjustment of light levels. This has made it possible to show paintings in close proximity to drawings related to them.

At the heart of the exhibition are the two versions of The Virgin of the Rocks, facing one another at either end of the main room. Although the compositions are very similar, each creates a very different impression. The figures in the Louvre version, which is universally considered the earlier of the two, are slightly smaller than those in the London picture, as well as livelier and more individualized. But the most obvious difference comes from the fact that the Paris picture is covered with a layer of dark varnish, which softens the contours and adds a sense of mystery to the landscape, whereas the version in London is brighter, with all the forms more precisely indicated and more easily visible.

This Issue

February 9, 2012

Václav Havel (1936–2011)

The Republican Nightmare

-

*

This information appears in a damaged document dated December 28, 1484, in the catalog. In fact, the document was written on December 23, a Thursday, indicating that the year must have been 1484 or 1490. It also includes the number 89, followed by proxime, indicating that it was written in the year immediately before or after 1489. Leonardo therefore could have taken up to seven years to deliver the altarpiece. ↩