For Rainer Maria Rilke the year 1903 did not begin auspiciously. He and his wife, the sculptor Clara Westhoff, were living in Paris, where the poet had come in order to write a monograph on Auguste Rodin. The Rilkes were not exactly dazzled by the City of Light. In a letter to his friend the artist Otto Modersohn, dated New Year’s Eve 1902, the poet spoke of Paris as a “difficult, difficult, anxious city” whose beauty could not compensate “for what one must suffer from the cruelty and confusion of the streets and the monstrosity of the gardens, people and things.” A few lines later he compares the French capital to those cities “of which the Bible tells that the wrath of God rose up behind them to overwhelm them and to shatter them.”

As one may gather, Rilke did not tend toward understatement, particularly when speaking of his physical and emotional health. In Paris he suffered a more or less serious nervous collapse, which no doubt clouded his view of the city. Writing from Germany in the summer of 1903 to his friend and sometime lover Lou Andreas-Salomé, he compared his sojourn in Paris the previous year to his time at the junior military academy at St. Pölten, where his parents had sent him as a boy in need of toughening up: “For just as then a great fearful astonishment had seized me, so now I was gripped by terror at everything that, as if in some unspeakable confusion, is called life.”

His description, especially in the long, extraordinary letter to Lou dated July 18, of the horrors he witnessed and suffered, was later transferred, in expanded form, into the Paris sections of his 1910 novel The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge. The people he encountered in the streets, he told Lou, seemed to him “ruins of caryatids upon which an entire suffering still rested, an entire edifice of suffering, beneath which they lived slowly like tortoises.” Baudelaire himself could not have written with more disgust, fearfulness, and desperation.

From his earliest days Rilke had been of a nervous disposition, to say the least:

Long ago in my childhood, during the great fevers of my illnesses, huge indescribable fears arose, fears as of something too big, too hard, too close, deep unspeakable fears that I can still remember….

His troubles began at home. Writing in confessional mode in 1903 to the Swedish writer and pedagogue Ellen Key, he told of his early boyhood spent in “a cramped rented apartment in Prague” with parents—German-speaking, Catholic—whose marriage “was already faded when I was born” and who separated finally when he was nine. His mother had wanted a girl, and christened her son and only child René Maria. “I had to wear very beautiful clothes and went about until school years like a little girl; I believe my mother played with me as with a big doll.” No wonder he could write to Lou in 1903, when he was in his late twenties, “I am still in the kindergarten of life and find it difficult,” and confess that “I am, after all, a child in your presence, and I…talk to you as children talk in the night: my face pressed up against you and my eyes closed, feeling your nearness, your safety, your presence.” As to his actual mother, “I see her only occasionally, but—as you know well—every encounter is a sort of relapse.”

Throughout his life he provided himself with a series of mother-substitutes, beginning with the redoubtable Lou and, if he had been able to have his way, ending with her, too. In 1925, when he was already dying, he wrote to her in desperation—“Now I send you this shabby bank note of distress: give me a gold coin of concern in exchange for it!”—but her response was as briskly indifferent as that of Proust’s Mme de Guermantes to poor Swann when he tried to convince her that he was fatally ill.1 Yet perhaps we should not blame Lou for missing the mortal note in Rilke’s pleas, since he had cried wolf so often in the past. Exalted whining was the prevailing mode when he was writing to his many lovers, confidantes, and patronesses. Indeed, it is a tribute to the compelling force and, one must add, the sweetness of his personality that so many of them continued throughout his life to indulge his solipsism and lavish self-pity.

Rilke’s letters are not letters in the usually accepted sense.2 There is none of the chat, the gossip, the backbiting that add spice to the correspondence between even the loftiest of souls. The voice here is a rhapsodic drone, and there is much introversion—me, me, me, and more me—and windy expatiation on the joys and sorrows of composition. He lives in superlatives, in the grand Germanic tradition, so that one seizes on the occasional humble fact with the eagerness of a pig lighting on a truffle.3 On the other hand, one cannot but be impressed by the passionate dedication with which Rilke addressed the task of living—living as a poet, that is. He craved solitude—“I am my own circle, and a movement inward”—and was prepared to sacrifice much to secure it. Having dithered for a long time he finally married Clara Westhoff in 1901, but almost immediately realized that domesticity held little bliss for him, and quietly detached himself from wife and baby daughter.4 As he remarked to Lou, with devastating candor, “What are those close to me other than a guest who doesn’t want to leave?” Nor did he think he should be expected to earn his bread by the sweat of his brow: “The very feeling that there is a connection between my writing and the needs of the day is enough to make work [that is, writing] impossible for me.”

Advertisement

This, then, is the neurasthenic young poet who in the late autumn of 1902 received a letter from a nineteen-year-old military cadet named Franz Kappus, himself an aspiring writer, enclosing some of his poems and requesting guidance and advice on the literary life he was embarking upon. Conceive of his surprise and pleasure when a few months later, in February 1903, he received a long, earnest, and thoughtful reply, the first of a series of ten epistles—the Pauline echo is not inapt—that Rilke would send to the young man over the next five years. Letters to a Young Poet is one of Rilke’s most popular books—if we may call it his book, since it was assembled by Kappus after the poet’s death—well known to poets in their youth and an ideal handbook for beginning writers. Mark Harman’s burnished, elegant new translation is the fifth English version, and likely to become the standard one.

Although no doubt Rilke considered Kappus a fellow sufferer caught up in the workings of the “officer dispensing machine,” the young man by his own account seems to have thoroughly enjoyed his time at the military academy he attended in Wiener Neustadt: “Instead of solving higher order equations I solved the sexual problem, instead of acquainting myself with spherical trigonometry, I acquainted myself with spheres that earned me the sobriquet ‘swine.’” It is to be hoped that Rilke did not read the biographical sketch of Kappus by Kurt Adel from which this debonair confession is taken. More than once in the letters he undertakes to counsel Kappus on the more esoteric aspects of sex—sex in the head, or at least the heart—and cautions him strongly against indulging in irony. By the time Adel’s sketch of Kappus’s life was published in 1920, the former cadet had become a popular novelist, a fact he alludes to somewhat shamefacedly in his preface to Letters to a Young Poet, where he writes that after his correspondence with Rilke had dried up, life had driven him “into the very areas from which the poet’s warm, gentle and touching concern had sought to preserve me.”

Certainly, in the letters, Rilke sought to guide the young man along that higher road that he himself had set out upon so determinedly at a young age. Reading them, one is hard put to remember that Rilke was less than ten years older than the young man he was advising, for the tone of voice throughout is that of an elderly wiseacre who has seen the wide world and learned its sore lessons. In the first paragraph of the first letter, written on February 17, 1903, he strikes a gravely admonishing note:

I cannot say anything about the form of your verses, for I find all such critical intent quite uncongenial. Nothing could be less conducive to reaching an art-work than critical remarks: it’s always simply a matter of more or less fortunate misunderstandings. Everything cannot be so easily grasped and conveyed as we are generally led to believe; most events are unconveyable and come to pass in a space that no word has ever penetrated; more unconveyable than all else are art-works, whose mysterious existences, whose lives run alongside ours, which perishes, whereas theirs endure.

Surely this is not the same man-child who a few months later will be writing of his longing to press his frightened face against Lou Andreas-Salomé’s maternal bosom and hide from the world in the warmth of her embrace. As Mark Harman writes in his introduction, “Adept since early childhood at playing roles, [Rilke] puts on a confident mask for Kappus’s benefit.” No doubt Rilke was seeking to treat Kappus as he in turn had been treated by Rodin, the grand maître for the sake of whose wisdom and patronage he had been willing to endure the torments of Paris the previous year.5 Rodin had taught the young poet valuable lessons, lessons that were to sustain him throughout his artistic life.

Advertisement

When Rilke came to Paris he was still a High Romantic, brother-in-art to the likes of Novalis, Klopstock, and the Goethe of Young Werther. Rodin, almost offhandedly, pulled the young dreamer’s head out of the clouds and knocked some common sense into him. For the sculptor, work was everything: Il faut travailler—toujours travailler was his motto. As for inspiration, Rilke wrote, the mere possibility of it he “shakes off indulgently and with an ironic smile, suggesting that there is no such thing….” These assertions must have struck Rilke like thunderbolts. Suddenly it was not the emotion or the idea that mattered, but the thing.6 Rodin was, above all, a maker of things:

And this way of looking and of living is ingrained so firmly in him because he attained it as a craftman; as he was achieving in his art that element of infinite simplicity, of total indifference to subject matter, he was achieving in himself that great justice, that equilibrium in the face of the world that no name can shake. Since he had been granted the gift of seeing things in everything, he had also acquired the ability to construct things; and therein lies the greatness of his art.

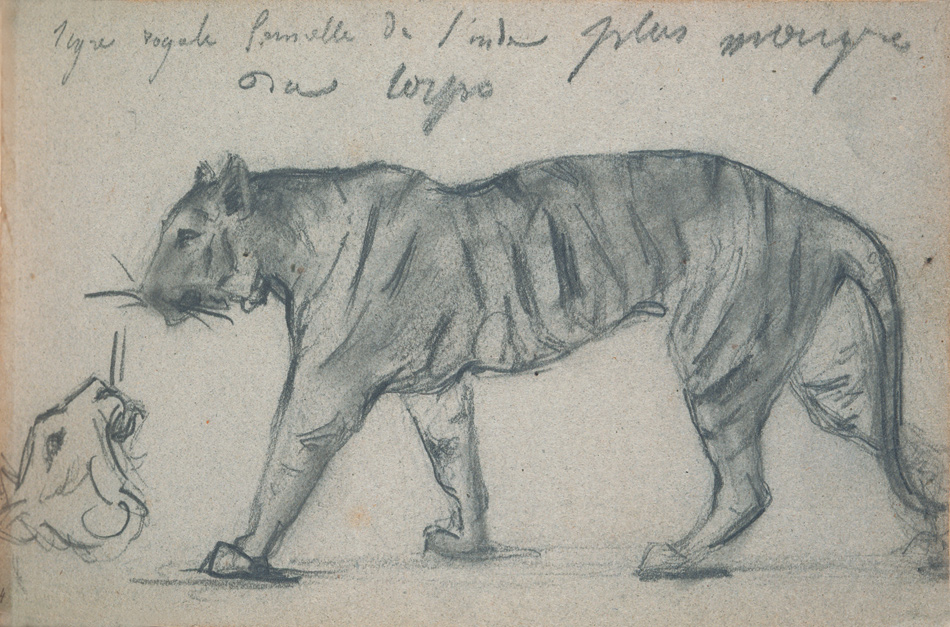

For Rilke, too, the Ding now became paramount. For him, “the history of endless generations of things could be sensed beneath the history of mankind,” and his ambition was “to be a real person among real things” and thus cure himself of what he wonderfully called his “breathing difficulties of the soul.” It was Rodin, so the story goes, who urged Rilke to take himself to the Jardin des Plantes in Paris and pick one of the animals in the zoo there and study it in all its movements and moods until he knew it as thoroughly as a creature or thing could be known, and then write about it. The result was “The Panther,” one of Rilke’s early masterpieces and as revolutionary in its way as anything by Eliot or Pound.

Despite what he had learned at the marble knee of Rodin, however, Rilke had no illusions about the solitariness of the artistic project, or its difficulty—“we must hew to what is difficult; everything that lives hews to it”—and was determined to impress his young correspondent with the hard facts of the creative life:

Nobody can advise you and help you, nobody. There’s only one way to proceed. Go inside yourself. Explore the reason that compels you to write; test whether it stretches its roots into the deepest part of your heart, admit to yourself whether you would have to die if the opportunity to write were withheld from you. Above all, ask yourself at your most silent hour of night: must I write?

Thus we see, behind this admonition, the journey into the self that Rilke had ventured on, and the complex aesthetic of inwardness that would find its comprehensive and triumphant expression in the Duino Elegies. The world of things is there, ineluctable, irrefutable, yet waiting on us and our transformative powers to help it achieve its ultimate apotheosis:

Erde, ist es nicht dies, was du willst: unsichtbar

in uns erstehn?—Ist es dein Traum nicht,

einmal unsichtbar zu sein?—Erde! unsichtbar!Earth, isn’t that what you want: to arise within us,

invisible? Isn’t it your dream

to be wholly invisible someday?—O Earth: invisible!7

For Rilke, life and the world are all potential. In an extraordinary passage in a letter to Kappus from Rome in December 1903, the poet responds to what must have been an expression of religious doubt by the young man,8 chiding him for saying that he had lost God—“Is it rather,” he asks, “that you never possessed him?” The God Rilke speaks of is “one who has been coming, the one imminent for an eternity,” and therefore we must live our lives “as a painful and beautiful day in the history of a great pregnancy.”

If he is the most perfect one, must not lesser things come before him so that he himself can choose from this fullness and profusion—Must not he be the last in order to embrace everything within himself, and what significance would we have if he, for whom we long, had already been?

In a similar vein he inverts our idea of carnal love, denying that it is, as we imagine, “a merging, surrendering and uniting with another person,” but on the contrary “a sublime occasion for the individual to mature, to become something in himself.” This notion of love as consisting of “two solitudes which protect, border, and greet each other” leads him on to a radical reassessment of the destiny of woman, who eventually will cease merely to “imitate male conduct, bad and good,” and become her true self, free of the “distorting influences of the other sex.” His thoughts here merit extended quotation:

Women, in whom life abides and dwells more immediately, fruitfully and confidently, must indeed have become in essence more mature human beings, more human humans than men, who being light and lacking the weight of bodily fruit pulling him down below life’s surface, undervalues in his arrogance and rashness what he claims to love. Carried to term in pain and humiliation, this humanity of woman will—once she has shed the conventions of the solely feminine through these changes in her external status—become evident, and those men who cannot feel this coming today will end up being taken by surprise and vanquished.

Hearken, o Mensch!

Heidegger once remarked that he was only trying to do in philosophy what Rilke had already achieved in poetry. On page after page of these masterly letters we are given ample instances of the depth of Rilke’s thinking and the philosophical reach of his imagination. In The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics Heidegger dwells at length—how else?—on the central function of boredom as a spur to human action, as a state of purest potential, a kind of affectless waiting as the spirit gathers itself for the leap into deed.

Rilke, anticipating the philosopher by some decades, writes from Borgeby Gård, his refuge in rural Sweden, in a letter to Kappus in August 1904, of the importance of being “solitary and attentive” because “the seemingly uneventful and static moment when our future enters into us is so much closer to life than that other noisy and fortuitous moment when the future happens to us, as if from outside.” In another passage, that could be from Emerson or William James, he urges Kappus, should he feel there is something sickly in his nature, to consider that “sickness is the means by which an organism frees itself from foreign matter,” and the organism, instead of being treated with curatives, should be helped to be sick, “to experience its illness fully and to erupt….”

Above all, these letters give the lie to the idea of Rilke as hopelessly self-regarding and cut off from authentic, “ordinary” life. His tone may be elevated and his manner at times that of a dandy—he was elevated, he was a dandy—but the advice purveyed in these letters, and the observations and aperçus that they throw off, contain true wisdom, and are anything but platitudinous. Franz Kappus was a fortunate young man to have found such a correspondent, and we are fortunate in his good fortune. Despite all the moaning and complaining; despite the lists of illnesses, mental and physical; despite his constant urge toward transcendence, Rilke was thoroughly of our world. In the ninth and perhaps greatest of the Duino Elegies he asks why we should persist in our humanness, and offers this beautiful answer:

…weil Hiersein viel ist, und weil uns scheinbar

alles das Hiesige braucht, dieses Schwindende, das

seltsam uns angeht. Uns, die Schwindendsten.…because truly being here is so much; because everything here

apparently needs us, this fleeting world, which in some strange way

keeps calling to us. Us, the most fleeting of all.

This Issue

January 10, 2013

Joy

Occupy the Rockaways!

How He Got It Right

-

1

The reader is directed to Rainer Maria Rilke and Lou Andreas-Salomé: The Correspondence, translated by Edward Snow and Michael Winkler (Norton, 2006), and in particular to the final, heartbreaking exchanges between the two. In these very beautiful last letters Rilke, dying of leukemia, displays heroic fortitude and unflagging candor:

You know how I made a place for pain, for physical pain, the truly great one, in my accommodations, but only as an exception and as already a first step back into the open. And now. It encases me. It supplants me. Day and night! Where to find courage?

The tone here echoes that of the final poem he wrote, a week or two before his death, the astonishing and exquisite “Komm du, du letzter, den ich anerkenne.” ↩ -

2

Aside from their content, they are physically beautiful artifacts. At Lou Andreas-Salomé’s suggestion Rilke had changed his handwriting—as well as his name, replacing the feminine-sounding René with the more masculinely Germanic Rainer—and he composed and graved his letters almost as carefully as he composed his poems. ↩

-

3

To Clara Westhoff, October 23, 1900: “I sent you yesterday a little package of a very excellent oat cereal to try. Directions on the package…. Try it, give me a report. The big California firm has other glorious preparations also.” ↩

-

4

The baby’s existence he found particularly disconcerting, although he did try to absorb the fact of her. Visiting her and her mother at Christmas 1905, he wrote:

I can’t say I find it a joy (it is too difficult)—but it is life that speaks to me with her small and strangely melodic voice, and as always I am a learner, and patient. And she looks just like I was as a child. It’s all a very remarkable experience.

Clara too was anxious to follow her artistic career unencumbered, and would leave baby Ruth for extended periods in the care of her remarkably accommodating parents. ↩ -

5

Rilke’s first meetings with Rodin were difficult for a number of reasons, one of which was the justifiably argumentative Mme Rodin—the sculptor was not an easy man to be married to—but the main one was the poet’s halting French. He was never to feel entirely at home in the language, yet he wrote a large number of poems in French, most of which can be found in two delightful and beautifully translated dual-language volumes, Valaisian Quatrains, translated by Peter Oram (Cardiff, Wales: Starborn, 2008), and Orchards, translated by Peter Oram and Alex Barr (Cardiff, Wales: Starborn, 2011). ↩

-

6

Ding, a word as vital to Rilke as it was to Kant and would be to Heidegger, but, as Mark Harman ruefully observes, “no more beautiful a word in German than it is in English.” ↩

-

7

The Selected Poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke, translated by Stephen Mitchell (Random House, 1982), pp. 200–203. Mitchell’s are the most satisfactory Rilke translations, although Edward Snow’s The Poetry of Rilke (North Point, 2009) is indispensable also. ↩

-

8

It is a misfortune that Kappus’s side of the correspondence has been lost, for there are numerous places where it would be illuminating to know what exactly were the questions and observations that Rilke is responding to. ↩