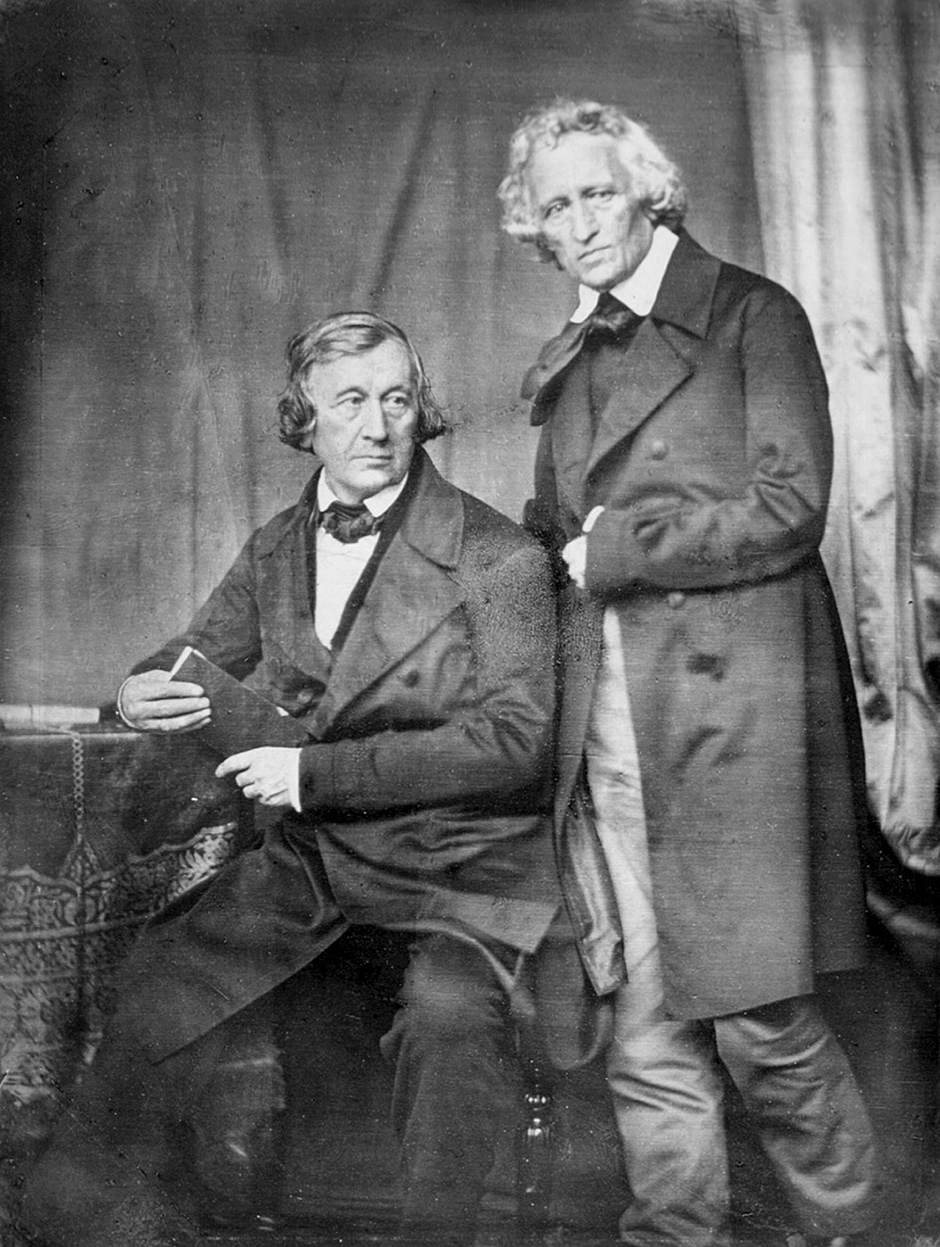

The Grimm brothers Wilhelm and Jacob were in their twenties and studying at the University of Marburg in the early 1800s when they were encouraged to collect German popular stories and other material by their law professor and mentor, Friedrich Carl von Savigny. Savigny was an important figure in the nationalist Romantic movement calling for Germany to be united politically and culturally; his friends and associates formed a tightly bonded, ardent group, caught up in the upheavals of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars. Their appeals for national recovery were combined with a quest for authentic voices of the Volk, the people.

The group included the writer and scholar Clemens Brentano (Savigny’s brother-in-law) and the poet Achim von Arnim, who was married to another sister of Brentano’s, Bettina, also a writer. Brentano and Arnim edited the influential songbook Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Boy’s Magic Horn) in 1805–1808, with its eldritch ballads from the folk tradition, such as “The Erl King.” The Volk could be heard, it was believed, in such songs, stories, lore, and language. The passion for Poesie, as the Grimms called the folkloric tradition, had already inspired in England an anthology of comparably terse, dark story-songs, Thomas Percy’s 1765 Reliques of Ancient English Poetry. That same passion infuses the magical and nightmarish poems of Coleridge in Lyrical Ballads as well as Wordsworth’s love of unlettered and unrecorded tradition:

Will no one tell me what she sings?

Perhaps the plaintive numbers flow

For old, unhappy far-off things,

And battles long ago…

The metaphors the Grimms used to describe their work are messianic and ecological: they believed they were saving authentic popular German culture, an endangered species. The preface to the first volume of the brothers’ tales Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales), published in 1812, begins:

When a storm, or some other catastrophe sent from the heavens, levels an entire crop, we are relieved to find that a small patch, protected by tiny hedges or bushes, has been spared and that some solitary stalks remain standing.

Of these few survivors, they wrote:

Ear upon ear will be carefully bound in bundles, inspected, and attended to as whole sheaths. Then they will be brought home and serve as the staple food for the entire winter. Perhaps they will be the only seed for the future.

This is how it seemed to us when we began examining the richness of German literature in earlier times…. The places by the stove, the hearth in the kitchen,…and above all the undisturbed imagination have been the hedges that have protected the tales….

The first volume was followed by another in 1815. Together these make up The Complete First Edition of the Grimms’ tales, presented and fully translated into English for the first time by Jack Zipes. (He has left out the voluminous apparatus that the assiduous brothers added, which effectively presented the book not as fun for the family but as documents toward a national cultural memory.)

This collection contains many of the most-loved fairy tales in the history of the form: “Little Snow White” (Sneewittchen), with its haunting refrain (“Mirror, mirror…”) and its three steps to deathly unconsciousness (first the stay-laces, then the poisoned comb, then the irresistible red red apple); the Grimms’ chilling and ferocious variant of “Cinderella” in which her sisters cut off their toes and their heels to fit into the glass slipper; “Rapunzel”; “The Robber Bridegroom”; “Fitcher’s Bird”—one could go on and on. The book is a classic, formed like a mosaic of precious small pieces, each one glinting with its own color and character, glassy and crystalline, but somehow hard, unyielding.

And yet much of it is unfamiliar. After the first edition was published, Wilhelm tinkered and tampered with the texts, trying to lighten the cruelty, patch over the sexual frankness (for example, the story of Rapunzel’s pregnancy), smooth over non sequiturs, and pattern the dialogue to match the most memorable tales. The two brothers revised and added to their collections several times. While the first volume (1815) includes fewer than seventy tales, by the Grimms’ final and definitive edition in 1857, the total had grown to over two hundred, many quite different from the original form presented here.

The brothers’ prose style diverges dramatically from that of earlier writers of fairy stories. These had tended to express feline licentiousness (Giambattista Basile), sophisticated comic irony (Charles Perrault), and rococo deliriums (Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy, who was the first writer to use the term contes des fées, in her book of that title in 1698). The Grimms’ stories are spare and austere. When James Merrill wrote that he yearned for

Advertisement

the kind of unseasoned telling found

In legends, fairy tales, a tone licked clean

Over the centuries by mild old tongues,

Grandam to cub, serene, anonymous,

he was referring to the Grimms, not to those older tellers of tales. Another recent translator of the Grimms, the English magical fabulist Philip Pullman, quotes Merrill approvingly, saying he was also aiming to capture this “tone licked clean.”

Zipes likewise admires the Grimms’ first collection for its extreme starkness and bleak matter-of-factness. He attributes this simplicity to its closeness to the storytellers and collectors who were the Grimms’ original informants: “This,” he writes,

is why the first edition of 1812/15 is so appealing and unique: the unknown tales in this edition are formed by multiple and diverse voices that speak to us more frankly than the tales of the so-called definitive 1857 edition.

(It so happens that Zipes has himself also produced a wonderfully useful, comprehensive volume of that “so-called definitive edition.”)

Jack Zipes, born in 1937, studied at Dartmouth and Columbia and then in Munich and Tübingen, and has been Professor of German at the University of Minnesota since 1989. He has long been a staunch advocate of fairy tales and their proper study since his book Breaking the Magic Spell (1979) issued a devastating blast against the wishful thinking of mass entertainment and shook the staid and soporific scene of folklore studies. To interpret the tales he has combined Marxism, feminism, cultural materialism, and even—for a short period—evolutionary biology. He has stirred readers with a similar passion for his material, while attacking the use of literary fantasy in movies and television to camouflage moral manipulation. Writers whom he admires—Jane Yolen, Terri Windling, and above all Angela Carter—and the films informed by their work have supplied countermodels to the sins of the dream factory.

In the epilogue of the new critical collection, Grimm Legacies, Zipes, drawing on the work of the philosopher Ernst Bloch, once again argues that fairy tales are best understood as utopian thought experiments. When the peasant crushes the ogre, the poor lad finds justice; persecuted by malicious relatives, the kind sister gets her due, the courageous girl saves her beloved siblings or lover. In an essay of 1930, “The Fairy Tale Moves on Its Own in Time,” Bloch writes:

What is significant…is that it is reason itself that leads to the wish projections of the old fairy tales and serves them. Again what proves itself is a harmony with courage and cunning, as that earliest kind of enlightenment which already characterizes “Hansel and Gretel”: consider yourself as born free and entitled to be totally happy, dare to make use of your power of reasoning, look upon the outcome of things as friendly. These are the genuine maxims of fairy tales, and fortunately for us they appear not only in the past but in the now.

Zipes is on a lifelong mission, as ardent as the Grimms’, to bring fairy tales into circulation for the general increase of pleasure, mutual and ethical understanding, and everyone in the field, including myself, has been helped by him: his prodigious energy seems as inexhaustible as the fairy-tale purse that never empties.

He has also worked fervently as a translator across a wide swath of German, French, and Italian literature from the medieval tales to modernist experimental fiction. (He is the editor of the current Princeton series Oddly Modern Fairy Tales, which has brought out collections by Kurt Schwitters and Béla Balász—the author of the libretto for Bartok’s Bluebeard’s Castle.

In 2002 a list of his works, drawn up in Marvels & Tales (the leading journal of fairy-tale studies), ran to seven pages. Since then, there have been dozens more publications, including the valuable encyclopedic survey of fairy tale films, The Enchanted Screen, as well as, most recently, the two books under review, in which his taste for polemic is undiminished, while his attention to historical setting and detail remain as productive as ever. In sum, Zipes has worked for over forty years to save the seed corn to which the Grimms likened their material, to guard its integrity and encourage its efflorescence.

The metaphors Zipes draws from nature and ecology can also help characterize the relations between oral, written, and dramatized folklore. The Grimms’ story “The Singing, Springing Lark,” about a young woman forced to marry a lion, can be seen as an example of an endangered German species of “Beauty and the Beast,” while Cocteau’s film La Belle et la Bête (1946), a more refined version of that same story, is a rare hothouse orchid. You could say Zipes’s oeuvre is a form of narrative husbandry.

What are the differences between the collections of 1812 and 1857? And, more importantly, do the differences in fact make a difference? After 1815, when the Grimms returned to their task, they left out as many as thirty-one stories, for various reasons. One was the grisly parable “How Some Children Played at Slaughtering,” in which the children, after witnessing the butchering of a piglet, kill one of their little friends. The brothers had come across it in a clipping in a newspaper edited by Heinrich von Kleist. This kind of cautionary horror story has the marks of urban myth, and shows how fairy stories were not the Brothers’ prime interest. Wundermärchen, or wonder tales, only formed a part of their vastly ambitious monument to the German popular tradition.

Advertisement

They wrote in the “Circular Letter,” distributed in 1815, that they planned to solicit materials from informants all over Germany. Jacob expressed interest in “folk songs and rhymes,…tales in prose that are told and known, in particular the numerous nursery and children’s fairy tales…local legends…animal fables…funny tales about tricks played by rogues…old legal customs,” and toward the end of the list, stories “about spirits, ghosts, witches, good and bad omens; phenomena and dreams.” The first edition throws its nets widely, though not quite as widely as this; surprisingly, this rich array of story forms does not include “fairy tales” (Feenmärchen) although Zipes uses the word in his translation; there are elves, goblins, witches, and dwarves, but no fairies.

Wilhelm, who was on the whole a mild and gentle soul, wanted to keep the child murderers in the later editions, because he thought they contained a valuable warning not to confuse make-believe and reality. But the story roused furious protests from readers and was set aside as too savage. The brothers were also keen to purify their research by concentrating on Germanic ethnic origins, and some of their decisions heightened the brusque callousness of the collection. The first edition includes “Puss in Boots” and “The Three Sisters.” By taking out such tales because they were too French or Italian for a monument to the German Volk, a certain polish and grace was lost. Instead, the Grimms’ collection presents a particular comic or savage hopefulness. Many of the stories end in revenge, rather than transformation or redemption. The evil queen in “Little Snow White,” for example, must wear red-hot iron shoes at her stepdaughter’s wedding, and dances herself to death. In later editions, Cinderella’s ugly sisters’ eyes are pecked out, whereas in Perrault, Cinderella lets bygones be bygones.

Other stories in the first edition were excluded because they were insufficiently oral in character, too scrappy, or too repetitive. The whittling could have gone on and on if the Grimms had applied their often inconsistent criteria more uniformly. They wanted the tales to come from known sources. Two dazzlingly well-turned tales—“The Juniper Tree” and “The Fisherman’s Wife”—were sent to the brothers as written texts in the Pomeranian dialect by the Romantic visionary painter Philipp Otto Runge, who did not identify his informants. The Germans used them anyway.

The Grimms also acknowledged that the wonderful, shivery tale of “The Singing Bone” bears a resemblance to the famous Scots ballad “The Twa Sisters,” also known as Binnorie/Minorie, which is still sung in many variations. (On YouTube you can hear Ewan MacColl and Emily Portman sing versions of it.) The plot of the ballad is essentially a ghost story about a sister who murders her younger sister over a man. In the Grimms’ tale, rivalry between brothers over a princess drives the plot. But the central, haunting motif of the bone that denounces the murderer recurs in both stories: a passing shepherd sees it sticking out of the riverbank where the murderer has buried the body of his or her victim. In the Scots ballad, it’s the breastbone—which the shepherd strings with the golden hair of the victim. In the Grimms’, it’s a femur or some such. He trims it for a mouthpiece for his pipe and then finds when he puts his lips to it that it sings of its own accord: “Dear shepherd, blowing on my bone…/My brothers killed me years ago!” In his own translation of the final 1857 edition, Zipes has a rendering that cries out with more urgency: “Oh, shepherd, shepherd, don’t you know/You’re blowing on my bone!”

The translator and fiction writer Peter Wortsman places this story toward the start of the admirable Archipelago Selected Tales of the Brothers Grimm and follows it with “The Tale of the Juniper Tree,” another story that contains that “playful—and therefore paradoxically comforting—terror” of the very best Grimms tales. In this tale, an evil woman kills her stepson so that her daughter, Marlenikin, will inherit the family’s money. She then cooks the boy into a stew and serves him up to his father. When Marlenikin buries the boy’s bones under a juniper tree, he reemerges as a beautiful bird who sings his misfortunes. Wortsman wants, he says, to keep “the sting and the bite of the original,” but he likes to add a witty twirl as well:

My mother, she smote me,

My father, he ate me,

My sister, sweet Marlenikin,

Gathered all my little bonikins,

Bound them in a silken scarf,

And lay them under the juniper tree.

Tweet, tweet, I’m a pretty birdie, look at me!

Those “bonikins”! You can hear the translator’s dark glee under the bird’s warbling.

Comparing 1812 with 1857, the effect of Wilhelm’s revisions across the whole edition becomes clearer. Dortchen Wild, later Grimm after she married Wilhelm, was one of nine children of neighbors who were close family friends; she is the first source of “The Singing Bone,” but later the brothers amended it, with the possible help of another woman narrator, and Wilhelm both elaborated and trimmed the story, adding an opening “Once upon a time” and tying up loose ends, such as the confession of the evil sibling: “After the fate of the murdered man was revealed, the wicked brother could not deny the deed, and he was sewn up in a sack and drowned.”

This gruesome justice does not appear in the first edition. Such additions increase the dark mystery of the fairy tales; the characters are without depth but their blankness gives them something of the feel of a black hole into which the reader plunges. Pullman goes so far as to write, in his introduction to Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm, “one might almost say that [they] are not actually conscious.” Some of this weird emptiness has inspired a long tradition of using silhouettes to illustrate the tales, and Andrea Dezsö’s graphic scissorings included in Zipes’s Complete First Edition pay tribute to the suggestive shadowplay of predecessors like Arthur Rackham and Lotte Reiniger (see illustration above).

The Grimms made much of their quest for authentic, oral transmission, but in practice, as several scholars (Donald Haase and Maria Tatar, as well as Zipes) have pointed out, they broke their own rules frequently. The list of sources includes a host of highly literate and literary precursors and associates. Their dream of the uncontaminated peasant legacy became embodied in the contributions of Dorothea Viehmann, an innkeeper’s daughter, who passed on forty of the best stories. A fine engraving of her by Ludwig, the Grimms’ younger brother, appeared as the frontispiece of the 1819 edition of the Grimms’ tales. It became an icon of the wise crone, the symbol of a living archive and fount of ancient, pristine lore. The brothers had been strongly encouraged to make their scholarship a bit more family-friendly by including Ludwig’s illustrations after they learned of the huge success in England of the first English translation by Edgar Taylor (1823 and 1826), with its quirky, joyous drawings by George Cruikshank. In Grimm Legacies, Zipes relates how the tone of the English illustrations changed the tales’ reception, inspiring Dickens to write sentimentally about their innocence, and Ruskin to claim that Cruikshank’s “original etchings…[are] unrivalled in masterfulness of touch since Rembrandt.”

The picture-book was poised for glory in a niche market, the new child readers of the professional classes, and the Grimms would inspire dazzling imaginative illustrators: besides Rackham and Reiniger, Walter Crane, John D. Batten, Henry Justice Ford, the enameled and sumptuous Edmund Dulac, and more recently Maurice Sendak and David Hockney helped imprint the Grimms’ words on generations; their images have transmitted the tales independently of Disney’s cartoons, another crucial medium. In the early years of the studio, when Walt himself was working, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) captured rather accurately the Grimms’ ambiguously mixed atmosphere of malice, dread, jollity, and mawkish sweetness. Wortsman’s Selected Tales of the Brothers Grimm steps out of the pictorial conventions altogether, juxtaposing richly colored, phantasmic, and voodoo-inspired paintings by various artists from Haiti with the well-known stories.

The transition from oral to written is not, however, clear cut, and the complexity of the process can be sensed in the complete first edition. The brothers’ task was more ideological than they could have known. What was and is German lore and story? As in the fields and hedgerow they invoked, seeds from elsewhere would blow in on the wind and take root and bloom; the horizons of fairy tale are vast, and likenesses appear at great distances from one another, mysteriously regardless of language, let alone political borders. In some sense you can invert the Grimms’ project and say that they were not saving an existing German corpus of story as much as brilliantly and successfully helping to establish it themselves as the foundation of a modern state and its identity—with consequences they could not have imagined and are not responsible for. The artist Anselm Kiefer, for example, born in March 1945, has entered the dark forest of fairy tale, grail legend, and national myths to track the tragic disfigurement of German Romanticism in modern times.

When Italo Calvino created his anthology Fiabe italiane (1956), Italy’s equivalent of the Grimms’ tales, he praised the oral storytellers’ liveliness, “realism,” and “imaginative language,” but he nevertheless took a crucial step and decided to rewrite the material. His approach runs counter to folklorists’ basic principle of fidelity to the source, but it reveals the central difficulty the Grimms encountered, that on the page oral versions can fade and falter. Performance adds vital elements: the speaker literally breathes life into the words. Wilhelm kept fiddling with the texts because he rightly sensed something was missing; Calvino turned his own luminous gifts for literary narration to the foundational voices of his country because he felt that it was necessary.

Folktales and fairy tales are literature from the era before silent reading; for most of us the Grimms’ tales no longer rely on print to be told and retold but after over two hundred years, the abrupt, sharp tales the brothers published have become richly patined with memories of such performances—musical versions, films, television series…as well as parents’ and schoolteachers’ readings.

In 2009 the news that around five hundred fairy tales, collected by the nineteenth-century ethnographer Franz Xaver von Schönwerth, had been found in the Regensburg municipal library in Germany created headlines. The Grimms have achieved one of their ambitions: nobody casually exterminates fairy tales. The scholar Erika Eichenseer sifted and transcribed and published them in German as Prinz Rosszwifl (Prince Dung Beetle); in English they have now appeared under the less rebarbative title The Turnip Princess. The eminent Harvard professor of comparative literature Maria Tatar acts as the presiding good fairy at this christening, and lively and lucid as ever, has translated, introduced, and annotated around seventy stories, making for an anthology comparable in size to the Grimms’ first edition.

An enthusiastic folklorist working in Bavaria, Schönwerth, a contemporary of the Grimms, saw his task in the same terms as the brothers: to rescue local storytelling from extinction. Jacob Grimm knew of his work and praised it highly (“No one in Germany has gathered tales so thoughtfully and thoroughly and with such finesse”), yet strangely Schönwerth does not appear among their contributors, and Zipes is also silent on the subject. Schönwerth’s collection has some of the same stories as the Grimms (e.g., “Seven with One Blow”) and shares many motifs and characters—with variations. There are also migrants and blow-ins from the Arabian Nights (“The Beautiful Slave Girl”). But it presents interesting differences because, above all, as Tatar points out, his Cinderellas, tricksters, and even blond beauties are male. Typical is the tale called “Lousehead” about a poor boy shunned because he always wears a cap:

“Which one of you wants to marry Lousehead?” The two eldest [sisters] remained silent, but the youngest smiled, gave him her hand, and then took off his cap. Everyone could now see that he had golden locks rather than an itchy scalp.

Lice turn up in the Grimms’ tales, too, in “The Three Golden Hairs,” for instance, but Schönwerth’s dramatis personae exist even more closely to the poverty line, in harsh urban conditions and on unforgiving farm land, rather than on the edge of wild forests; the prose is blunt, the dynamics plain and simple; “cunning and high spirits,” the fairy-tale motives that Benjamin admired, win out again and again; vengeance is absolute. Metamorphoses take place—into toads, snakes, calves, cows, weasels; magic is a means to a worldly end. The turnip princess of the title story has a magic instrument—a rusty nail; hazel nuts rather than roses feature in a tale called “Ashfeathers,” which combines elements of “Beauty and the Beast” and “Cinderella.”

In one of the most intriguing stories, “The Enchanted Quill,” the feather from a (female) crow turns into a pen: “If you use it to write down a wish,” the crow tells the heroine, “the wish will come true.” She first asks for “the very finest dishes” and plays gleeful tricks on unwanted suitors. Here the transition from the sung charm to the inscribed spell has become embodied in an active and magic pen. Yet a silent reader of Schönwerth’s tales still feels the need for performance, to blow this horn, to breathe some warmth into these bones and make them sing.