Persuading people to like something is a trade. Persuading them to change their minds and like something else is a skill. But inducing them to believe in something that their senses and experience tell them is plainly unreal or untrue—unicorns, papal infallibility, Trump’s assertions, ghosts—requires art and almost manic self-confidence. The “confidence men” of Margalit Fox’s title, two British prisoners of war who planned the most eccentric and devious of all escapes, had plenty of both. But Fox puts their story into a broad historical setting, using it to illustrate the ways in which scientific inventions made possible not only empowerment but also credulity and manipulation.

It’s often pointed out that we live in an age of lies. Vulgar postmodernism proposes that what matters about a statement is not whether it’s true, but what its effect is. In that sense, alternative facts rate as facts even if they are shown to be false. Posts on social media platforms are not expected to be strictly truthful by their billions of users, and resisting crass persuasion—the sales patter of stall-holders in the market—can even be enjoyable. Over a year ago, the algorithms planted around me began inexplicably to translate into Polish the many e-mail entreaties to collect my vast Nigerian inheritance, celebrate my Bitcoin fortune, or snatch an unguarded account in a Malaysian bank—easy to recognize and swat away. But the daily assault by the whirring cloud of criminal persuaders that rushes up from my laptop reminds me that there was a time when con men were rare and startling to encounter.

We are now enduring, courtesy of the Internet, a new onslaught of the mind-bending industry. Fox’s subject is its first great upsurge, which began to peak in Europe and America in the late nineteenth century. As she brilliantly shows, this was a time when scientific discoveries and inventions, especially in communications, began to seem miraculous. Normal rules of perception appeared to melt. Words could travel across the globe on “waves,” things invisible and ungraspable. On the phonograph, men and women spoke from beyond the grave. Humans found that they were descended from monkeys and began to fly. And at the same time spiritualism—the resort to mediums for sibylline wisdom or contact with the dead—began to flourish among educated people, even among scientists, as never before. Fox writes:

Today, most of us view scientific rationalism and spiritualist belief as mutually exclusive. But in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as one modern observer has noted, “science was to a degree the ally of ghosts.” The reason was simple: in order to define what is supernatural, one must first define what is natural, and in those years the border between the two seemed far more porous than it does now…. If technology had the power to do all those things—to transcend space, time and the body’s innate opacity [she is referring to the discovery of X-rays]—then what was to say, scientists reasoned, that communication across the ultimate divide was not possible, too?

Fox’s two escapers, E.H. (Harry) Jones and Cedric Hill, found themselves in a Turkish prison camp for officers during World War I. Their breakout tool was not a tunneling shovel but a Ouija board, which they used to establish almost total dominance over their captors. In their slow and crafty campaign, they resorted to a battery of techniques, including physical conjuring presented as magic; “trance-talk,” which foretold future events; “theory of mind” (Fox’s term for awareness of what another might be thinking); “equivoque” (the art of forced selection, as when a subject “chooses” a card covertly preselected by the magician); and “coercive persuasion,” sometimes known as brainwashing. Fox’s book emerges as a sort of didactic collage, its central escape narrative regularly breaking off to discuss controversial moments of scientific history: the rise of spiritualism, the fashion for “alienism” among those who treated mental illness, the development of sophisticated scamming, or the trade secrets of manipulation by conjurers and magicians.

Jones was a Welshman from a middle-class academic family. Hill was Australian, a tough young man brought up on cattle and sheep ranches who was dexterous with his hands—and a good conjurer. Jones had been captured after the British defeat by Ottoman forces at Kut al-Amara, one hundred miles south of Baghdad, in 1916 (Fox gives a long and horrific account of the siege); Hill’s aircraft was shot down over Sinai. They met in the officers’ prison camp at Yozgad in the barren hills of central Anatolia—a group of empty houses that had belonged to Armenians murdered in the genocide that had begun the year before. Conditions were bearable but bleak.

Advertisement

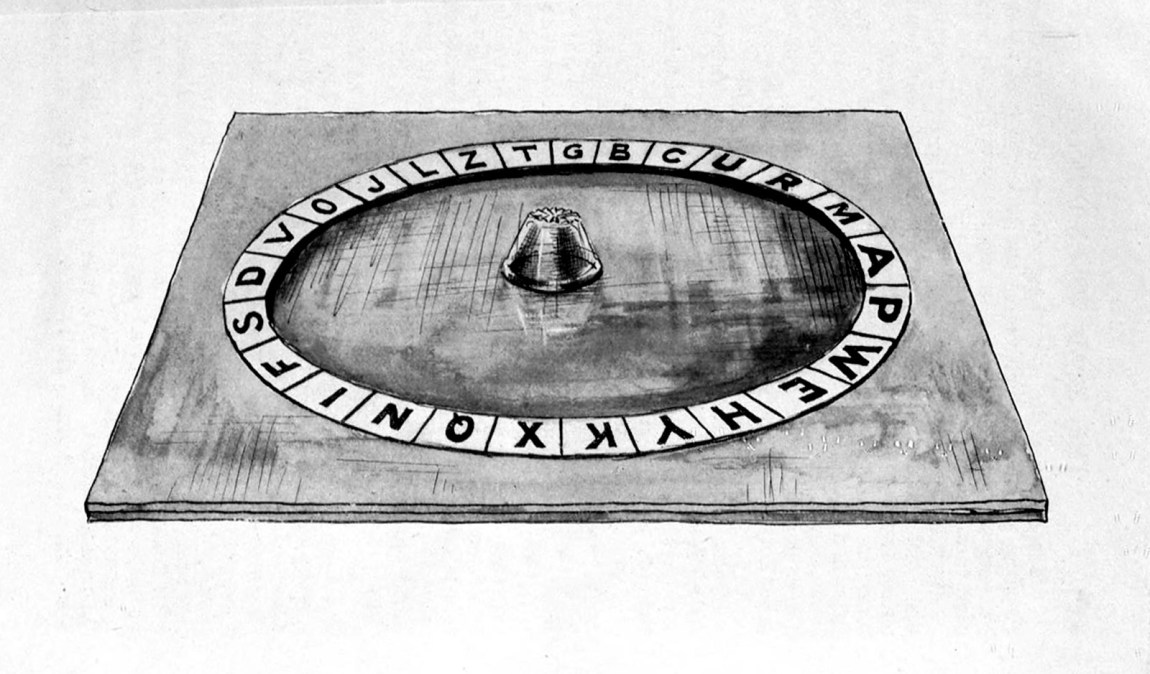

An aunt wrote to Jones suggesting that he could amuse himself by making a Ouija board. (For those who have never seen one, this is a popular divination kit in which “unseen forces” are supposed to make a handheld glass or pointer travel around letters on the circumference of a flat disc, composing a message.) Jones made one, and soon bored young officers started to crowd around. But no comprehensible words emerged until Jones discovered how to steer the marker-glass with an invisible twitch of his thumb, at which point someone named Sally began to deliver flirty messages from the ether. Jones decided not to break the spell, and soon a crew of jolly phantoms were describing their walk down Piccadilly or their dinner at the Trocadero. “We conversed with Shackleton on his South Polar expedition, with men in the trenches in France,” wrote Jones. “A successful night at the spook-board was the nearest we could get, outside our dreams, to a breath of freedom.”

Only Jones could evoke coherent words. But other prisoners were amazed to feel the marker-glass moving under their hands, apparently without their volition. Fox identifies this as “motor automatism,” comparable to the way a water-divining twig seems suddenly to twist in the fingers. The young Gertrude Stein, when still a student at Radcliffe, researched this condition of “divided consciousness,” in which one read aloud while resting a hand on a planchette (something like the Ouija glass equipped with a pencil), which performed “automatic” writing. Fox goes on to summarize the great spiritualism craze and the rise of the professional (and commercial) medium:

By the late nineteenth century there were reported to be 8 million spiritualists in the United States and Europe. The movement had reached Turkey in the 1850s…. If spiritualism was an article of faith, it was also extremely good business, and within short order the medium had emerged as a new breed of solo entrepreneur.

Jones had begun running his Ouija circle as “no more than a leg-pull, ‘a rag, with no definite aim in view.’” In April 1917 an aim suddenly presented itself. The camp commandant, Major Kiazim, was a dignified, remote figure. But his assistant and interpreter, an Ottoman Jew named Moïse Eskenazi, was fascinated by the British prisoners and in almost daily contact with them. Although Jones and the others despised him, referred to him as “the Pimple,” and made him the target of often anti-Semitic mockery, Eskenazi emerges as the most interesting and even sympathetic character in the story. He was incurably hopeful and trusting, pathetically vain, constantly the fall guy in the intrigues of bigger and nastier men. “The Pimple” was fascinated by Jones’s séances and gave him a list of questions to put to “the Spook,” a sort of presiding deity invented by Jones as the head of the Yozgad spirits. Jones saw a chance: “I made up my mind to grip this man, and to wait for time to show how I might use him.”

The moment came a few months later. Eskenazi, by now convinced that the Spook was offering real information from the Beyond, asked Jones if it could locate a hoard supposedly buried by a rich local Armenian before his expulsion and death. Commandant Kiazim, Eskenazi hinted, was behind his inquiry and was a firm believer in ghostly powers. Exultant, Jones saw a possibility of manipulating his captors into allowing him to escape. By organizing a treasure hunt and conspiring secretly with a prisoner, Kiazim and Eskenazi would be irrevocably compromised and under his control. Yes, he told Eskenazi, he and the Spook of course knew about the treasure, but so far only in vague outline.

Summoned at last to meet the commandant, Jones dramatically appeared to read his thoughts—guessing, on a pretty safe bet, that Kiazim was thinking about the treasure and how to find it. The commandant was hooked. Jones and his accomplice Hill now planned to entrap him securely. Clandestine photographs of Kiazim engaging with prisoners in a hunt for buried treasure could be used to block any inclination he might have to punish the remaining prisoners after the two of them escaped. Meanwhile Jones, as spirit medium, transmitted the communications of the Spook as he “revealed” the story of three Armenians—close friends of the treasure’s owner—who had each been told the location of one clue.

Two of the friends were dead, communicating from the “other side.” But the third, reported the Spook, was still alive, living in Constantinople and—conveniently—making frequent business trips to the Turkish coast opposite the island of Cyprus, then under British control. The two Armenian ghosts were induced to tell the Spook where to find the dead men’s two clues: tins with false bottoms, prepared and buried by Hill, containing a coin and a mysterious message written in Armenian script. (The third clue did not exist.) At the same time, another angry phantom invaded the Ouija board. Known only as “OOO,” he was proclaimed by Jones and Hill to be the original owner of the treasure, powerful enough at times to supposedly seize control from the Spook and bring all communication to a halt. As Fox points out, OOO was what magicians call an “out”: a convincing excuse to explain malfunctions in their “magic.”

Advertisement

Digging began, and the first two clues were unearthed. Compromising photographs clearly showed the commandant and Eskenazi standing with Jones over a pit. But how to leave Yozgad? Hill and Jones decided that they must feign madness and persuade their captors to escort them to the mental hospital at Haidar Pasha, just across the Bosporus from Constantinople. To practice their act, they demanded to be confined in a house separate from the rest of the camp inmates as they worked up their symptoms. Could they arrange to be given a prison sentence to justify their move? Kiazim was at first unwilling. But they managed to convince him that they were guilty of “espionage by telepathy,” transmitting and receiving war news on thought waves. A sham trial was held. Kiazim, whose only motive now was to pursue the next clues to the treasure, presided and ensured a guilty verdict. When the witnesses had left, he, Eskenazi, and the two prisoners burst into triumphant laughter. Kiazim was fooling his own superiors, unaware that Jones and Hill were fooling him.

The fake madmen rehearsed “lunacy” as they waited for Kiazim to send them to Constantinople. Jones imitated “general paralysis of the insane,” brought on usually by syphilis and requiring—so he decided—wild and irrational outbursts. Hill chose “religious melancholia,” sitting on his bed and endlessly rereading his Bible. Finally, Kiazim gave permission for the journey. The escapers’ plan now was to divert from the route, on fictional Spook orders, and head for the coast, supposedly to meet the “third Armenian.” There they would overpower their escort, seize a boat, and set a course for Cyprus.

Then disaster struck. Another officer-prisoner, knowing nothing of this plan, somehow concluded that Kiazim was only letting Jones and Hill out of Yozgad in order to kill them in the wilderness and rid himself of their troublemaking. So he wrote to the commandant alleging that the two planned to escape and should not be allowed out of the camp. Kiazim didn’t believe this—he still trusted his “mediums.” But the trip to Constantinople had to be canceled.

The great plot had collapsed. But the two prisoners had one remaining asset: Kiazim and Eskenazi, although now terrified of what Turkish higher authorities might do to them, still believed in their power to locate the treasure through spirit messaging. For months, Jones and Hill kept up their pretenses of insanity, eventually convincing military doctors that they were mad enough to be accepted as mental patients at Haidar Pasha. They finally set off under escort in April 1918—faking a suicide attempt on the way that nearly went wrong and killed them both—and were settled into the hospital’s “nervous ward” in early May. While Eskenazi completed their admission paperwork, Hill staged a gloomy Bible reading, and Jones, pretending to believe that he had reached a hotel, loudly ordered a whiskey and soda.

What followed was a long, agonizing anticlimax. Months passed; the pair’s performances of madness—including starving themselves—brought them to the edge of genuine breakdown. But the authorities kept putting off their repatriation to Britain, while Turkey’s best German-trained “alienists” studied them and subjected them to more tests until, at last, a medical panel certified them as credibly insane. Emaciated and groggy, they boarded the prisoner-exchange ships in early November 1918.

But only a few days earlier, on October 30, the Armistice of Mudros had ended the war between the Allies and the defeated Ottoman Empire, and the release of all prisoners had begun. In other words, all those years of plotting, suffering, mind-bending, and deception had been pointless. If they had stayed patiently behind the wire at Yozgad, playing camp soccer to keep warm, the outcome would have been no different. Naturally, Jones and Hill didn’t think so. Both wrote books about their experiences. Jones’s memoir became a best seller in the years between the wars, joining escape classics found in every British school library alongside H.G. Durnford’s The Tunnellers of Holzminden (1920), about twenty-nine officers who escaped from a German prisoner-of-war camp in July 1918—the largest escape of the war. Only the next war’s fresh crop of tunneling and wire-cutting epics obliterated these books from memory, so Fox has done popular literature a service by disinterring them.

She uses long extracts, especially from Jones’s The Road to En-Dor (1919), on many pages. The story is so outlandish that readers may ask if it’s true. Both men included large slabs of dramatic dialogue in their books (mostly between themselves and their captors), which are obviously fictional reconstructions. But that was the literary fashion of the time, and enough of their fellow prisoners from Yozgad wrote memoirs that confirm the narrative’s outlines. It falls into two parts: the use of the Ouija board and the Spook to direct the will of Kiazim and his assistant, and then, after the original plot collapsed, the period of feigned madness designed to earn repatriation. The first is by far the most interesting. The second section, describing those endless, monotonous months of suffering in the hospital, is moving, but on its own that story would never have tempted Fox to write a book about it.

She is concerned with coercive persuasion, the techniques people have developed to convince others to believe what isn’t true. And with the Yozgad escapers she enters this especially fascinating period of transition in which scientific advances based on severely rational deduction had ironically released a new flood of credulity. Some of the techniques employed by conjurers are delightful: Fox devotes two pages to a list of an accomplice’s word codes designed to tell a blindfolded magician what audience members take out of their pockets. Other tricks involved the use of imposing bits of psychic equipment: the “telechronistic ray,” which supposedly connected minds, or the Four Cardinal Point Receiver, a thought-reading engine. Jones and Hill assured their captors that they could operate both of these.

By any standards, their Turkish jailers were gullible. Folk cultures, including Turkey’s, abound in stories about the cunning tricks used by the weak—mice, peasants—to fool the strong. How could the commandant and his staff not have been suspicious when their prisoners introduced them to spooks and Armenian ghosts demanding changes in camp routine? But Fox points out that most of the camp inmates had already been won over by Jones’s charades: “Once a critical mass of captives came to believe in the Spook, it became that much easier to convert the captors.”

And yet, was it only the Turks who were credulous? These events took place at a time when Great Britain was winning a world war and commanding a global empire that was just reaching its brief but gigantic maximum. Fox acknowledges the orientalism and sheer racism in how Jones and Hill perceived their world. The Turks? They regarded them as lazy “natives,” really: negligent and superstitious and unfit to rule other peoples. An equivalent Spook was persuading British officers that their own race was physically and morally superior to all others. The rest could certainly be trained to serve and cooperate. But “orientals” should not automatically expect the courtesy and consideration usual among the “civilized.”

When the armistice was announced, Commandant Kiazim sent for the senior British officer in the Yozgad camp, held out his hand, and said, “The war is over; we are now friends.” The British officer ignored his hand and replied, “The war is over. You have lost, we have won. In future you will take your orders from me.” Kiazim burst into tears. After the war, Eskenazi wrote a series of long, affectionate letters to Jones, hoping that they could resume their friendship; in spite of everything, he still believed that the Spook had secrets to reveal. Jones kept these letters but answered none of them.

This Issue

December 2, 2021

‘And I One of Them’

Herring-Gray Skies