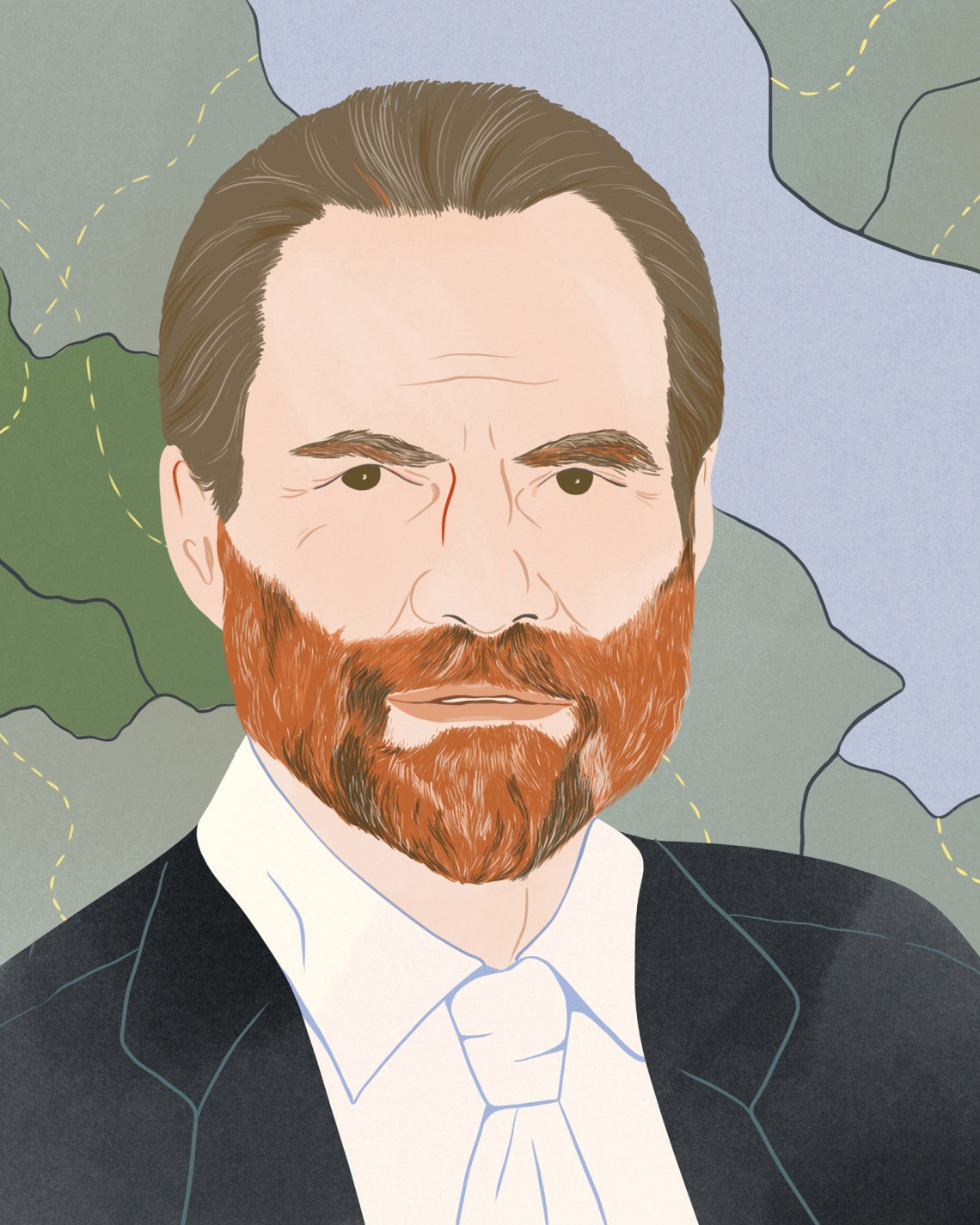

Why a “personal history”? Why not just a “history” of Europe in the postwar and post-Wall generations, or (if you like) during the long interval between George Patton’s tanks and Vladimir Putin’s? The answer is that if you are English, there is still a deep-down need to explain why you identify as European. Timothy Garton Ash is profoundly English, and the core of his most recent book, Homelands, is the narrative of his own emotional formation—of his transition from enjoying Europe’s thrilling but “foreign” diversity, its sheer difference from stolid old Angleterre, to a passionate identification with this region that has become for him what Mikhail Gorbachev used to call “our common European home.”

As such, Homelands is really three things. It’s an account of “the European project” and its unsteady experiments with unity. It’s a subjective tale of the author’s encounters and self-discoveries. And—in effect—it’s a long reflection about British attitudes toward the worlds beyond the Channel. Garton Ash was a schoolboy when he first went abroad alone, to France in 1969, leaving behind his sturdily upper-middle-class parents. For his mother, “European” meant being white in British India. For his father, a brave artillery officer who had landed on the D-Day beaches and fought with his men from Normandy to Germany, “Europe was definitely foreign and the European Union was one of those ‘knavish tricks’ that our national anthem calls upon patriotic Brits to frustrate.” A lifelong Conservative, he shocked his son by briefly defecting to the xenophobic UK Independence Party, and if he had lived long enough he would certainly have voted to leave the European Union in the 2016 Brexit referendum.

The elder Garton Ash’s view of Europe—I am closer to his age cohort than to his son’s—brings back voices from my own childhood. Europe was a huge, dark place “over there.” The German bombers that shook our house came from Europe, and so did awful, half-comprehended stories about war crimes and hunger. Later, after the war, I heard the old British fascist Oswald Mosley trying to revive his fortunes by preaching a “United Europe” free of Communists and nonwhite immigrants. Later still, in the 1950s, Labour Party orthodoxy warned that the nascent European Community was a right-wing plot devised by Catholic capitalists in France and Italy.

For me, though, a different light had broken through midwar when the headmaster of my first school read to us a poem newly smuggled across the Channel: Paul Éluard’s “Liberté.” Stunned, I dreamed of a Resistance Europe, its peoples united in heroic conspiracy against Nazi occupation. (It was not until I was first sent to learn French in France, like Garton Ash some twenty years later, that my fantasy of a universally Maquisard France was mocked out of me.)

For decades, and above all since the Solidarity uprising in Poland in 1980 and the reemergence of Central and Eastern Europe over the next eleven years, Garton Ash has been witness, reporter, and on occasion policy adviser on European affairs. A believer in the importance of individuals in history, he has made his way to the offices and lunch tables of the great: Gorbachev, both Bush presidents, Pope John Paul II, Helmut Kohl, Margaret Thatcher, Donald Tusk, Konstantin Chernenko, Václav Havel—the list is awesome. What he brings back from these meetings is not so much a journalist’s sound bites as highlights from serious, speculative conversations among experts united in their concern for Europe. At least two of them, Havel and free Poland’s first foreign minister, Bronisław Geremek, became lifelong friends. Garton Ash never met Vladimir Putin face-to-face, but he had the luck, at a conference in St. Petersburg in 1994, to hear a then obscure city official rise and angrily proclaim Russia’s rights over neighboring lands that had “historically” owed allegiance to Moscow. His view of Russian intentions has always been rather Polish—immune to optimism, to put it mildly—and when he heard that speech he guessed what it could mean.

But Garton Ash is no Lanny Budd—that irritating know-it-all figure in Upton Sinclair’s novels who is somehow always there to talk down every top-table meeting. “Being there” is Garton Ash’s practice, not just with the elites but with ordinary people among the fire-gutted houses, with bewildered crowds of refugees, or in defiant protests (he often marches, too). “Place” matters to him, and he starts Homelands by visiting two well-named European villages, Westen (in Germany) and Osten (formerly in Germany, now in Poland and renamed Przysieczyn). Westen is where his father ended up with his men in the spring of 1945. Collective memory in both places recalled not only the monstrous slaughter and destruction of that war but also the millions driven from their homes by invading armies and changing frontiers: “Here was Europe’s mad carousel of involuntary displacement.” From this desolation grew a generation, maturing in the 1960s, of young men and women who had often grown up without fathers, dead in the war or held for years in labor camps or prisons.

Advertisement

As a student in Oxford and then Berlin, “naïve and full of Cold War clichés,” Garton Ash set out to explore this fascinatingly divided Europe. “For the next five years,” he writes, “I pursued a kind of self-made apprenticeship in life under communist rule”: Yugoslavia, Albania, East Germany. But this was a rather detached survey, almost intelligent tourism, until he encountered Poland. There, in the Lenin Shipyard at Gdańsk as the Solidarity rebellion erupted, his fascination with Europe’s division became a commitment, an imperative to join the struggle for a freedom he soon identified with the cause of a “Europe whole and free.” He has stayed faithful to that ever since, proclaiming at the time that “Poland is my Spain”—a call to action as noble as the call to defend Republican Spain in the 1930s.

In retrospect, he sees that the Western nations that overthrew dictatorships to join the European Community in or after the 1970s—Spain, Portugal, Greece—made the same link: “Freedom meant Europe and Europe meant freedom. This is a way of thinking quite alien to most Brits, with their different historical experience” of no censorship, free speech and association, plural and open democratic politics, and a market economy. But Garton Ash is no dogmatic neoliberal. When communism collapsed in the course of 1989, many of his friends among the young leaders of underground resistance and “velvet revolutions” were heretical Marxists, hoping for a sweepingly radical but open and purified socialism. (Who now remembers that Solidarity began as a movement for workers’ control of industry: anarcho-syndicalism, in fact?) But by then many people—especially in Poland—were turning away from designs for a reformed socialism. As Garton Ash puts it, they “simply wanted the freedom, prosperity, civilised life and normality of countries like West Germany, France and Britain.” If “normal” meant a regulated capitalism, so be it. At least it seemed to work.

Neither group got what it wanted. The leftist revolutionaries were soon elbowed out of the ministries they had taken over by older, more “professional” politicians. The people who had longed for a “normal” Western economy faced callous, bewildering transitions. They became the subjects of imported neoliberal experiments, often driven by wild-eyed Hayekian or Friedmanite fanatics like the ones I met in Warsaw as communism foundered in 1989. Racing through the corridors of the National Bank, they were hunting down and uprooting all state subsidies and unprofitable public institutions. (“Leave one twig of socialism in the ground and the damn thing will sprout again!” one told me.) On the contrary, Homelands shows that political liberalism and social democracy can live together happily, as they currently do in Germany or—in periods of Labour government—in Britain. But back then, the reformers simply sent Poland’s entire planned economy over Niagara in a barrel. That generated the mass unemployment, inequality, and sense of abandonment that led to a historic backlash: the populist and illiberal Polish governments that, until the rebuff of the Law and Justice party in October’s elections, were starting to paralyze Poland’s membership in the European Union.

Europe, the narrowing western peninsula of Eurasia, is a fish trap. Migrating peoples have poured into it for millennia, thrashing and struggling as they find they can go no farther. It’s also a paradox: a quadrilateral with only three sides. There is ancient ambiguity about where Europe ends—at the Urals, at China’s border? And there is historical ambiguity about confidently linking Europe to “freedom.” Europe brewed the ideologies of fascism and “national egoism,” as well as Marxism, capitalism, and Garton Ash’s liberalism, which puts its trust in the decent instincts of individuals. The tank and the gas chamber are no less native to European ingenuity than the steam engine and antibiotics.

It’s easy to forget that those postwar decades of peace were a blessing confined to the continent’s northwestern nations; by the time Garton Ash reached disintegrating Yugoslavia in the 1990s, Europe had already suffered the Soviet crushing of Hungary in 1956, Bulgaria’s expulsion of Turks and Roma, the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, and the Irish Troubles. Now he crossed burned-out landscapes in Krajina and Bosnia, met survivors of the Srebrenica massacre, and later in Kosovo saw the bodies of innocent men in snow reddened with blood. “Europe,” the Brussels Europe, did not come out of that well. It’s impossible to forget Jacques Poos, head of the European Council, telling the world to stand back as conflict broke out: “The hour of Europe has dawned.” But nothing much beyond futile protest ensued, until NATO and the Americans pushed “Europe” aside and used bombs against Serbia. In besieged Sarajevo, Garton Ash writes, people “spat out the word ‘Europe’ with acid contempt.”

Advertisement

So did the Greeks a decade later, pauperized by the European Central Bank during the debt-driven crisis of the eurozone. In an especially lucid chapter, Garton Ash describes the “triumphalist” mood as monetary union became “the central political project of European integration” in what he calls “post-Wall Europe.” There were warning voices—“I was among them,” he says—who asked how a common currency could work with no fiscal or banking union, and no political union to control it. When the crash came, an ugly gulf opened between Greek public opinion, recycling images of wartime Nazi occupation, and German prejudice against nations perceived as reckless Mediterranean scroungers wasting Berlin’s hard-earned money. For a moment, the glow of European reconciliation seemed to dim: “Here was the heart of the matter: the disjuncture between policies that were already European and politics that were still national.” But northern European and especially German tightfistedness and obsession with book-balancing seem not to have survived Covid-19. In 2020 no less than €750 billion were raised to help European nations recover, more than half of it in grants rather than loans. Perhaps the pandemic has left one real gain behind: a worldwide relaxation about limits to government debt and spending.

Two helpful and at times heartbreaking sections of the book take up immigration and attitudes toward Europe’s growing Muslim population. Appalled as he was by the murder of the Charlie Hebdo journalists in 2015, Garton Ash stuck to his liberal principles: the offensive cartoons of the Prophet must be republished. Whatever the danger to journalists, he argued, the assassin’s veto must not prevail, and he launched an appeal calling on all Europe’s media to reprint the cartoons together, which “failed comprehensively.” But he continued to investigate. He interviewed Moroccan refugees who had scaled the fence at Ceuta to reach Spanish territory and Muslim teenagers in a grim Paris suburb. In a striking passage, he samples the lurid Islamophobia that at the time threatened to drench European readers in cultural pessimism. Among the examples were Thilo Sarrazin’s Germany Abolishes Itself, Éric Zemmour’s The French Suicide, and Michel Houellebecq’s satirical novel Submission, in which a Muslim Brotherhood candidate becomes president of France and the Sorbonne is turned into an Islamic university.

Fear of “alien minorities” and paranoid nightmares of cultural replacement date back to the immediate aftermath of World War II. Europe saw the flight and forcible “transfer” of millions after 1945. This was also a gigantic ethnic cleansing, as states expelled their minorities, national or religious, to achieve “homogeneity.” (Poland, vividly multicultural before 1939, is now almost 88 percent Catholic and 98 percent Polish-speaking.) In 2015 a new so-called refugee crisis opened as millions, from war-devastated Syria and Iraq but also from Africa, pressed across the Mediterranean into Europe. Donald Tusk, then president of the European Council and now the victor in Poland’s October elections, argued forcefully that keeping Europe’s internal borders open, as dictated by the Schengen Agreement, required the reinforcement of its external frontiers. Steel fences and razor wire went up, an ironic recall of old cold war barriers. Thousands of migrants have drowned at sea. Yet the slow, immense movement of humanity from Global South to North is ultimately as irresistible and planetary as climate change. Garton Ash sees this but offers no solution:

In theory, one might argue that liberal, open societies should have open borders. In practice, that would rapidly spell the end of liberalism in most such societies, especially those with a high standard of living.

Well before the new emergency of the Ukrainian war, the European “project” had left three huge questions unresolved. How can the European Union advance to closer political union when most national governments and publics now feel that integration has gone far enough? How does one manage a common currency zone without the enhanced political authority to lead it? And how can values of openness and democracy prevail while the continent barricades itself against fugitives, refugees, and would-be Europeans from the south?

A few years ago Garton Ash watched again the film of Britain’s magnificent Olympic pageant in 2012, which celebrated all that was generous and lively in the country that is still his. It made him weep tears of patriotic affection, but also tears of sadness for what ensued: “Brexit and the divisions that accompanied and followed Brexit.” In the 2016 referendum, his own nation had turned away from his crusade for a “Europe whole and free.” For him it was both a political and a personal tragedy. Contemplating the post-Brexit United Kingdom, an increasingly lonely and wizened state drifting out of international significance, he confesses,

I had an idealised, rose-tinted picture of Britain such as could be kept intact only by a privileged white Englishman who spent much of his time abroad. Today, I view the country of my birth more critically.

He rejects the cliché explanation that “the British never really felt at home in Europe” and were bound to leave sooner or later. However, it was the English and the Welsh—not the entire UK with its minority nations—who voted decisively to quit the EU. Scotland and Northern Ireland chose just as decisively to remain, but England has 85 percent of the UK’s population, so their choice was obliterated. Garton Ash’s own historical examples show that the obsession with sovereignty and the exaggerated fear that foreign immigration might dilute native identity have long been especially English, rather than British, anxieties.

Garton Ash is a conservative rather than a revolutionary kind of liberal. With no experience of the 1968 upheavals in Western Europe, which happened while he was still in school, he seems at first to dismiss them and their geyser of ideas as “Breughelesque extravagances.” But unlike many historians, he can recognize that the 1968 rebels in Warsaw and Prague and those in Paris and Berlin shared idealisms that were more than a coincidence. He goes on to describe the renewed threat of “accidental” nuclear war in the 1980s and the subsequent European peace movement. That became “the great political cause” of the day, but, he admits, “it was not mine.” Instead he stood by his dissident friends in the dictatorships to the east who feared that unilateral reductions of American warheads would do nothing for their liberty and only give confidence to their Soviet oppressors.

Gorbachev took command of the Soviet Union in 1985. Previously unthinkable arms treaties unfroze the cold war; the Berlin Wall and Communist regimes in most of Europe came down in 1989; the Soviet Union itself collapsed in 1991. A silly “end of history” mood took hold in the West, welcoming “unipolar” American world hegemony and predicting eternal life for globalizing free-market economies. By then Europe was already enjoying a historic upswing: “If ever the stars aligned for freedom in Europe, it was in the second half of the 1980s.” Soon the nations freed from the Soviet imperium would be lining up to join the renamed European Union created by the Maastricht Treaty and aspiring to NATO membership.

Garton Ash sees that Europeans were not immune to the general hubris of the time and “soon started to make the mistake of regarding this as somehow the normal path of development.” Atrocious wars broke out in Bosnia and Kosovo. The September 11 attacks on the United States generated passionate sympathy across the Atlantic. But in the longer run, America’s furious response made its allies—Britain’s Tony Blair excepted—reluctant to support the invasions of Afghanistan and then Iraq. After talking to Vice President Dick Cheney, Garton Ash emerged sensing “the hubris of a superpower that felt itself globally predominant and yet impudently defied…. The ‘war on terror’ also changed US views of Europe and European views of the United States.” Though John Kerry insisted after his defeat in 2004 by George W. Bush that “America is not only great but it is good,” “that belief was shared only by a dwindling minority of Europeans.”

A rueful chapter of Homelands looks at how Europe’s mood of “excessive self-confidence” swelled and then deflated: “We linked our dream of spreading individual liberty much too closely to one particular model of capitalism.” The eurozone crisis and the global financial crash of 2007–2008 punctured that arrogance, and for Garton Ash, a paradox in his own beliefs was revealed:

For liberalism to flourish, there must never only be liberalism. Western liberal democratic capitalism did so well in the second half of the twentieth century precisely because it was challenged by fierce ideological competition from fascism and communism.

China soon presented that sort of competition, but without noticeably restoring European confidence in its own market model. And as the new century reached its second decade, the euphoria of building a wider, democratic, and peaceful continent was ebbing fast.

Even before Russia invaded Ukraine, Garton Ash was uncompromising about the need to expand both NATO and the European Union eastward. Historians still argue about the fateful but bizarre Berlin meetings in early 1990, which Gorbachev’s team left thinking that they had a deal: if they accepted German reunification, then NATO “would not shift one inch eastward from its present position.” Those words apparently came from US secretary of state James Baker and were confirmed the next day by German chancellor Helmut Kohl. Incredibly, the Russians did not bother to get the deal written down and signed, and within months NATO was preparing the expansion that eventually recruited a chain of Europe’s ex-Communist states, including the Baltic republics, up to the Russian frontier.

Was Russia—still the Soviet Union in 1990—tricked and betrayed? Putin now insists on that, and most Russians agree with him. Was that Berlin encounter the last chance to create a historic new “peace order” and bring Russia into a single continental defense and security system replacing both NATO and the Warsaw Pact? Garton Ash—not always convincingly—denies that the West swindled Gorbachev, and he suggests that radical changes of circumstance, above all the disappearance of the Soviet Union a year later, justified NATO’s expansion. After all, given history, how could a neutral Poland—let alone an independent Estonia or Latvia—be left under Russia’s shadow, unprotected by any military alliance?

By about 2008 European self-confidence (and self-congratulation) was withering. After the eurozone panic and the global financial crash came the Covid pandemic and then the confrontation with Putin’s Russia. Garton Ash reproaches himself now for sharing the general hubris, including “the hubris of believing that the enlargement of the American-led geopolitical West into eastern Europe could continue smoothly without facing a fierce challenge from a revanchist Russia.” The fierce challenge came on February 24, 2022, and “Europe went all the way back” to the horrors of the 1940s.

Not only to the horrors. Europe and “the West” have now reverted to the broad pattern of that previous war: a political and military alliance of nations, headed by the United States, against a single aggressor. Since then Garton Ash has visited Ukraine many times and thrown himself wholeheartedly behind its cause. Long ago, it was accepted that only change in Moscow could effect change in Eastern Europe. Now, he suggests, it’s the reverse. Only through change in Eastern Europe, meaning the further expansion of NATO and the EU to include Ukraine, Moldova, and even Georgia, can change be brought about in Moscow. And Russia, he has hawkishly suggested, can only be saved by military defeat, as Germany was saved for eventual democracy by its defeat in World War II. That seems unrealistic. So, unhappily, does his remark that “the enlargement of the West does not entail the diminishment of Russia.”

Homelands is an irresistibly well-written book, fluent, witty, and intelligent. But it skirts around an America-shaped hole. In spite of all its integrations, the European Union still resembles a sort of coral reef, a beautiful, passive collective being, in and out of whose recesses wealth and ideas and migrants flow as the tides change. The rapid war-and-peace decisions of a nation-state are beyond it. Talk about a “European army” is simply embarrassing. Although there are many national armies, Europe will always need some external power to defend it. The EU was not devised by the United States, and Europe’s postwar economic recovery would probably have come about—though more slowly and erratically—if there had been no Marshall Plan. But without the American military guarantee and political interventions, sometimes resented and sometimes implicit rather than explicit, European governments would not have felt secure enough to set about merging their institutions.

To be complete, this book really needed a separate section on Washington’s changing policies toward Europe. As Putin’s aggression has driven neutral Finland and Sweden into NATO ahead of a crowd of other alarmed applicants, the distinction between the civil union and the armed alliance has blurred into a single “West” confronting Russia. But it was not so long ago that America’s policymakers grew disgusted with European reluctance to join the “war on terror”—Europe was “a pain in the butt,” Cheney told Garton Ash.

Reciprocally, European distrust of US reliability has only grown. What would be the impact of a second Trump presidency on the European Union? Just possibly that of a healthy shock, forcing a shift to coherent leadership. But it’s more likely that if Europe begins to doubt America’s will to defend it, fear of Russia and dissolving confidence in NATO will drive more nations to turn inward and loosen their ties to the EU. There would be a retreat from unity toward a mere treaty-league of sovereign states. But for Garton Ash, who calls himself a “Euro-Atlanticist,” such a breakdown of trust between continents might be replaced by something even bigger and better. He dreams of “a wider, not merely transatlantic community of closely cooperating free countries, also embracing the many people who live in unfree countries but yearn to breathe free.” That seems to be President Biden’s vision, too. It is a very long way off.

—November 21, 2023