William Shakespeare’s best-remembered sonnet compared someone to a summer’s day. The poet Johannes Becher, once East Germany’s minister of culture, compared the essence of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) to a sonnet. According to Philip Oltermann’s The Stasi Poetry Circle, he “believed that sonnets structurally mirrored the Marxist view of historical progress,” the materialist version of Hegelian three-stage dialectic from “an idea, the thesis, to a contradiction of that idea, the antithesis, to a solution that resolves the tension between these two ideas, the synthesis.” Thrilled by his discovery, Becher wrote that “the sonnet makes its content life’s law of motion…statement, contrast and resolution in a concluding statement.”

This view was solemnly accepted by the Circle of Writing Chekists, selected members of the Stasi—the East German secret police—who wrote poetry and met once a month to read and criticize one another’s verse. Most were from the elite Feliks Dzerzhinsky Guards Regiment, named after the ferocious founder of Lenin’s security police, the Cheka, and writing poetry was anything but a hobby for them. Art was a weapon in the struggle against the ever-vigilant class enemy. Oltermann suggests that to the Stasi “the sonnet was the algorithm that would guide East Germany’s population…gently into freedom.” Later he expands on this idea of “the good poem as a miniature model for the good society”:

A state with steady feet and a perfectly calibrated rhyme structure would learn to wind its way through the corridor of history to the steady beat of thesis, antithesis and synthesis, just as the sonnet unfurls down the page.

But the GDR never had steady feet and was felled by its own antitheses in 1989, only a short way down that corridor. Oltermann is right to say that the history of the GDR is usually told back to front: “The images that prevail are of the spectacular last scenes,” the torrential flights across opening borders and the falling Berlin Wall, the immense protest marches and the gibbering panic of Communist leaders. But at the beginning, half a century before, there were noble hopes. The lands of the Soviet Occupation Zone, shattered by wartime slaughter, mass rape, and destruction, were still Germany, where—some fervently believed—the great German traditions of humanist thought and creativity might be reconstructed in a socialist state that could put the Nazi past firmly behind it.

Instead the Soviet occupation authorities fostered a political regime with an effective Communist monopoly on power, slavishly obedient to Soviet suggestions and models—including a secret police that would eventually swell to over 90,000 members relying on a stupendous network of so-called unofficial collaborators (inoffizielle Mitarbeiter, i.e., informers) numbering around 190,000—roughly one police spy for every sixty East German citizens. But many in the regime, including survivors from the mighty pre-Nazi German Communist Party, clung to their faith that the new Socialist Unity Party might still develop independent “German” authenticity and popular support.

Walter Ulbricht, odious and inflexible, dominated the regime for decades. The working class, he pronounced, must storm the heights of culture. Johannes Becher had already said much the same thing: there should be no distinction between workers who worked and workers who wrote, and literature should not just reflect social conditions but shape them. Writers were sent to the factories, and not without impressive results: Christa Wolf’s novel Divided Heaven, for instance, followed her spell in a plant constructing railroad cars. Every branch of industry or employment was encouraged to set up “Circles of Writing Workers,” and the Stasi, in establishing the Writing Chekists, was merely falling into line.

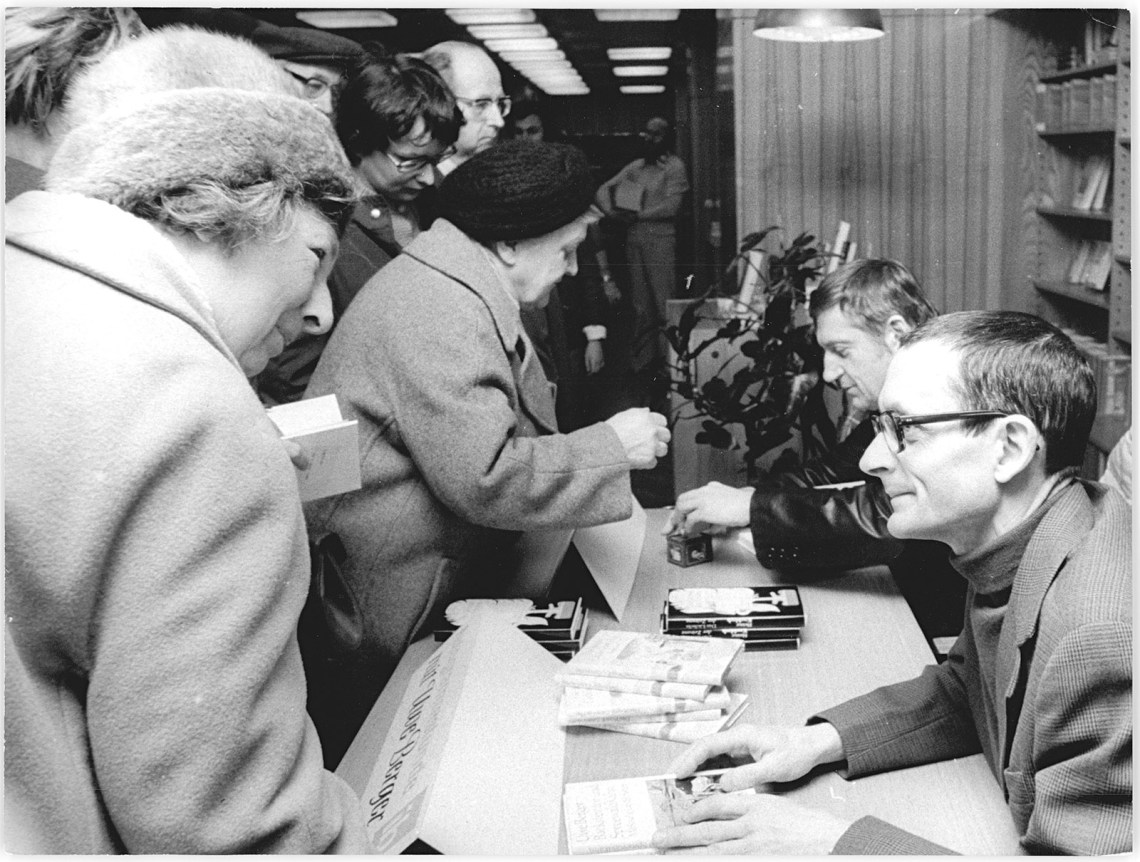

Today Oltermann is a much-admired correspondent for The Guardian in Berlin. But in 2015, traversing a bad patch in his personal life, he was living in London and working with a poetry circle of old people in a community center. The job reminded him of an East German booklet he had picked up years before, a 1984 anthology of verse by those Writing Chekists, and once back in his native Germany, he set out to find and study them, thirty years after they had become ex–Stasi agents nervously seeking new identities. Some had died—one by suicide. But others agreed, often reluctantly, to talk to him and share their memories. Oltermann concentrates on six men at the core of the group: a border guard, a clerk in the Stasi archives, two members of the Stasi paramilitary unit, an officer in the propaganda section, and a professional poet.

The poet was Uwe Berger, who was appointed the circle’s leader in 1982. A prolific, paranoid informer on his own Stasi pupils—a spy within the spy ring—Berger was middle-aged by the time of his promotion and had a long list of published work and state prizes. But Oltermann (himself well trained in literary criticism) simply cannot understand his reputation. Berger’s poetry was painfully boring, lightened by no flash of imagination or metaphor. Even East German editors and critics found him dreary and second-rate, for all his dogged loyalty to the party line. The secret of Berger’s success seems instead to have been his twenty years’ previous service as an unofficial collaborator with the Stasi, industriously reporting on everyone he knew or came across who said or wrote or hinted at anything critical of party or state in the GDR or the Soviet Union, or favorable of the “class enemy” in West Germany.

Advertisement

To judge by the excerpts in this book, Berger’s student Chekists were not very talented either. (Oltermann is a resourceful translator, but it would have been fair to give his Chekists a chance by including some of their original German texts.) There was one exception: Alexander Ruika, a very young conscript who had already been widely published in the GDR and had made the shortlist for the Berlin Literature Prize. The son of a Lithuanian German who had become a senior officer in the GDR’s armed forces, Ruika came from a privileged nomenklatura background that hardly fit the ideal of the “worker-writer.” But when the Circle of Writing Chekists heard this nineteen-year-old read his poem about the Red Cavalry in the Russian Civil War, they were speechless:

When Uwe Berger finally broke the silence in the room…he said something he had never said before in their circle. All the other Stasi men would remember it for years. “Look at this young man, comrades,” he said. “What a talent.”

With a dexterous translation and analysis, Oltermann tries to show how skilled the poem was in its mastery of metaphor, consonance, enjambment, and pace, as Ruika evoked the onrush of Marshal Semyon Budyonny’s horse-army. Even in English it reads well. And Berger’s praise was probably sincere, but it did not prevent him from later reporting to the Stasi that Ruika was politically unstable, “openly in favour” of East German institutions and values but “subliminally against” them.

As Oltermann notices, Berger’s comments could imply that this suggestible young man might make a good secret agent, and so it turned out. A few years later the writer Gert Neumann—wrongly suspected by the Stasi of plotting to immigrate to West Germany—ordered a taxi and asked to be driven to Leipzig. The driver was none other than Ruika, and the cab was equipped with microphones. When he struck up a conversation about literature and asked intelligent questions, Neumann rapidly grew suspicious. He possessed all the survival instincts required in that time and place, but he also shared in its ambiguities: as he paid the driver, he invited him to join a poetry reading in a Berlin church well known as a meeting place for the illegal opposition.

Ruika did not turn up for that. He wrote a few more striking, conflicted poems that he read to the Chekists but then faded out of the literary record. According to a Google search by Oltermann long after the GDR’s collapse, he was running a private investigation agency in Berlin. But later still, and after many hesitations, Ruika and Neumann agreed to meet again in Oltermann’s presence. Some thirty years had passed. The encounter, in a Greek restaurant, began awkwardly: Neumann told pointless anecdotes, while Ruika sat in puzzled silence. Then Neumann suddenly forced the other writer into something like an admission that he had been acting for the Stasi that night, and—with relief—the pair turned to gossiping freely about universities and books. Ruika, Oltermann writes, “is now retired, and spends his time repairing vintage motorbikes and occasionally writing poems.” Neumann moved to Wittenberg “to spend more time studying Martin Luther.”

The Stasi and the censors never felt that they had really understood Neumann’s novels or deciphered what he was saying in them. Their training assured them that all creative writing conveyed a sociopolitical message, and they suspected that Neumann’s message—hidden in cryptic prose crammed with strange allusions and enigmatic comments—was a hostile one. But they never decoded it. This was because there wasn’t any message. Neumann’s fiction was certainly opaque, but the truth was that the literary sentinels of the GDR were stupid—sometimes comically so. Oltermann quotes a sixty-two-line poem by Uwe Kolbe, approved by the censors and published, whose readers instantly saw that the first letters of each word formed this very different poem: “Your measures are miserable/Your demands enough for bootlickers/…To the victims of your heroism I dedicate/An orgasm.”

But for most writers intercepted by this literary police, the stupidity was grotesque rather than hilarious. Oltermann tells the story of Annegret Gollin, a clever and rebellious teenager who liked hitchhiking and writing poetry in a school exercise book. Picked up for “anti-social behaviour” because she refused to get a job, she accepted the Stasi offer to spare her punishment if she became an unofficial collaborator. A few months later she broke free, telling over a hundred friends about her recruitment.

Advertisement

Retribution followed. The Stasi pounced. In an absurdly elaborate operation, Gollin was snatched as she crossed a square in Zwickau, “a tiny grey figure in a tiny grey town.” Her apartment was raided, and a handwritten poem titled “Concretia” was discovered. Its two vertical columns of verse seemed to represent soulless apartment towers and ended with the line: “That’s not just the case in New York City.” Once in prison, she was interrogated about her poetry no fewer than thirty-six times:

The police could see what her poems said, but what did they mean?… Did this line mock the Socialist Unity Party?… Every air pocket of ambiguity had to be beaten out of the pieces of paper the spies had retrieved from Gollin’s flat…. The Stasi could not quite fathom what they were dealing with. The charges against Gollin bring to mind a terrorist building home-made explosives, not a teenage girl jotting down her insecurities in her bedroom: “In 1977, she made the decision to practice subversive agitation in written form. To achieve this aim, she made use of certain expertise she had acquired in a literature club.”

The court case was put on hold when Gollin revealed that she was pregnant, and after she gave birth she received a two-year suspended sentence. But only two years later Gollin left her son with a babysitter, went to a dance hall with friends, and got fiercely drunk. “By 6 PM, she had had nine shots of Mocca Edel schnapps” when she ran into a man suspected (correctly) of being a Stasi informer and spat in his face. Twenty months of imprisonment followed. Her child was sent to a state home and his father was found dead in suspicious circumstances.

When Oltermann tracked Gollin down a few years ago, she was working as a tour guide in Berlin’s restored Chancellery, at the time the offices of Angela Merkel. She had been one of the 1,491 prisoners sold to the West for hard currency—some 40,000 deutsche marks each—seven years before the wall came down. Her retirement pension, together with compensation for her imprisonment, will amount to only €714 a month (about $750), whereas “the German state still pays the pensions of former Stasi employees, on average around 1,400 euros [about $1,475] a month.” Oltermann adds: “Annegret Gollin no longer writes poetry.”

The Stasi Poetry Circle is mainly concerned with events in the 1980s, East Germany’s final decade, when the Writing Chekists were at once most active and most troubled. The regime’s clumsy attempts to enforce discipline on the creative arts were still overshadowed by the disastrous Biermann affair a few years earlier. Wolf Biermann, who would become the greatest German singer and songwriter of his generation, had grown disaffected with the stifling parody of socialism around him. By the 1970s he was performing lyrics (such as the superb “Ermutigung”—“Encouragement”) that inspired the young on both sides of the wall to rebel, and in 1976 the GDR tried to silence him by revoking his citizenship and “expatriating” him to the West. To the shock of the authorities, the country’s best-known writers participated in a public protest against Biermann’s treatment: the first act of organized defiance in the GDR’s cultural history.

The Biermann affair, or rather its bungling, must have contributed to the growing lack of self-confidence among the Writing Chekists in the 1980s. But their international outlook was darkening too. In the rest of the Soviet bloc, Communist regimes—especially in neighboring Poland and in Hungary—were losing their grip on society, often relaxing censorship and introducing elements of market economies. The GDR went the other way, increasingly isolated as it insisted on Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy and enlarged the secret police. Meanwhile the cold war entered a final, acutely dangerous phase, as a new array of Soviet SS-20 rockets provoked the United States into stationing cruise and Pershing missiles in West Germany. NATO’s huge “Able Archer” military exercise in 1983 could look like the prelude to an all-out nuclear onslaught on the Soviet Union—and not only to the Stasi poets. The apocalypse felt close.

The Writing Chekists, now less worried about cultural subversion from the West, were more concerned with the spread of the Swords to Ploughshares peace movement across East Germany, but some of the younger Stasi poets shared the movement’s horror at the prospect of nuclear war. Gerd Knauer, from the Stasi propaganda unit, read to the circle a long, terrifying poem about the landscape left by the nuclear doomsday. After passing piles of mutilated, charred corpses and encountering gangs of cannibal rapists, the narrator meets a woman with two heads who asks: “Who took a stand/against this ghastly fate?/Was there too little fear at hand?”

This was scarcely the language expected of an officer of the Stasi, an organization whose motto was “Shield and Sword of the Party.” When Knauer finished reading, one member of the audience rushed to the bathroom. Uwe Berger told the group that the poem was “very technically advanced” but reproved Knauer afterward. “Did Knauer realise,” Oltermann writes, “that this ‘fear poem’ was at odds with his ideological mission in the Ministry for State Security?” Knauer disagreed. Berger complained to his superiors about “Comrade Knauer and his uptight, pig-headed personality,” but there was nothing noticeably uptight about Knauer when Oltermann discovered him in reunited Berlin. He had hoped, at the end, that some sort of purified Stasi might survive in a democratized successor state to the GDR. But his faint optimism had dissolved on January 14, 1990, when he found himself in the Stasi building as the crowds stormed it and hurled its secret files out the window. In the changed world of a united capitalist Germany, he wrote crime novels and joined a tax consultancy for Ossis (ex–East Germans) bewildered by the new complexities.

It’s hard to judge when—if ever, before the fall of the wall—the Stasi poets definitively lost their faith. Their morale was typical of those who know their professions are hated and take that hatred as proof that their work is necessary. A floor below the poets’ meeting room, there was a wall plaque with a portrait of Feliks Dzerzhinsky that proclaimed, “Only someone with a cool head, a hot heart and clean hands can become a Chekist.” How clean did the Stasi poets consider their hands, which were responsible for lies, blackmail, intimate treachery, monstrous penal injustice, and the maintenance by police terror of suffocating public fear and suspicion? Annegret Gollin described her country as a place where “you could fuck everyone and trust no one.” But the plaque also warned that “a Chekist has to be more clean and honest than anybody else. He has to be as clear as a crystal.” Oltermann, with an eye for metaphor, points out that “most crystals aren’t clear at all, but cloudy…. If you want to keep a crystal transparent, you need to keep it in an artificial environment, isolated from the natural world.”

One can imagine Uwe Berger sourly surveying his circle of cloudy crystals and wishing they were more transparent. What were they really thinking? Some wore uniforms while the senior ones could dress as they pleased, but surely the definition of a true Chekist was that a class comrade could see right into his head and watch his thoughts as they assembled in their correct places. (Curious, this obsession with cleanliness and purity on the part of those who direct state crimes against humanity. At its extreme stands Heinrich Himmler, reminding SS officers carrying out the Final Solution about their duty to remain anständig—decent, respectable—while standing beside a thousand corpses.)

One of the problems with secret police forces, from a dictator’s point of view, is precisely that they know too much. If they are any good at their job, they are in touch with genuine public opinion and aware of how much it may contrast with official propaganda about mass support for the regime. The bearer of bad news, however, is taking a big risk with the state leadership. In the Nazi period, the SS security service dared to report with some frankness about what the German people were saying in private (lingering faith in the Führer but increasing loathing of Nazi Party “bonzes” and officials, perceived as corrupt parasites).

Stasi members were well aware of the regime’s unpopularity, but—almost to the last moment—seem to have been unwilling to confront the leadership with the facts. Perhaps this was because they feared for their jobs. But perhaps it was also because, in spite of decades of disillusion, they still could not bear to betray that fading mirage of a “better” Germany: austere, self-sacrificing, high-minded, and cultured. Oltermann writes:

Given that the East German state had invested so much time and effort in trying to nail down the ambiguities of the German language, it was only appropriate that when the final collapse came, it would…be…directly brought about by words that said more than they were meant to say.

The wall was breached because Günter Schabowski, the politburo spokesman, told a press conference on November 9, 1989, that it would be opened “right now, immediately,” when he was meant to say that some temporary passes would be issued the next day. Four days later Erich Mielke, minister of state security, was stupefied to be interrupted in the normally craven East German parliament. “Comrades,” he began. “There are not only comrades in this chamber,” said somebody. Mielke responded, “I love all humanity,” and his words were drowned in a roar of mocking laughter—words that “immediately became part of national folklore.”

On December 8 the Stasi was officially abolished. On December 31 permission was issued to print the final anthology of the Circle of Writing Chekists. The manuscript survives, with the title Writing Chekists crossed out and replaced by Lyrical Circle in the Office for National Security. A dedication to the fortieth anniversary of the GDR was also crossed out. “But,” Oltermann observes, “it never made its way to the printers.”

This Issue

February 9, 2023

Misreading the Cues

Beyond the Pale

The Other Cuba