To the Editors:

In his review of Robert Caro’s The Years of Lyndon Johnson: Master of the Senate [NYR, November 21], Marshall Frady errs in discussing the Civil Rights Act of 1957. He says that the legislation as first proposed “contained a crucial provision, Part III, outlawing segregation in schools and most public services, from parks to hotels to restaurants.” But Part III did not in terms outlaw segregation anywhere. It merely gave the United States government standing to bring lawsuits under Reconstruction-era statutes authorizing civil suits for the vindication of constitutional rights. Heretofore such suits had been brought by aggrieved individuals, e.g., Linda Brown of Brown v. Board of Education. The US Department of Justice was limited to expressing its view as a friend of the court. Part III would still have left it to the courts to decide whether segregation was unlawful in particular situations, though empowering the Justice Department to initiate such suits would have been an important spur to the process of desegregation.

In a compromise engineered by Johnson to get the bill through the Senate, Part III was dropped. Frady says that made passage of the bill “a phantom triumph.” It is true that the 1957 act proved toothless, as Frady says. But its passage proved that Southern filibusters could be broken: a great political and psychological breakthrough that helped open the way to the transforming civil rights legislation of the 1960s.

Anthony Lewis

Cambridge, Massachusetts

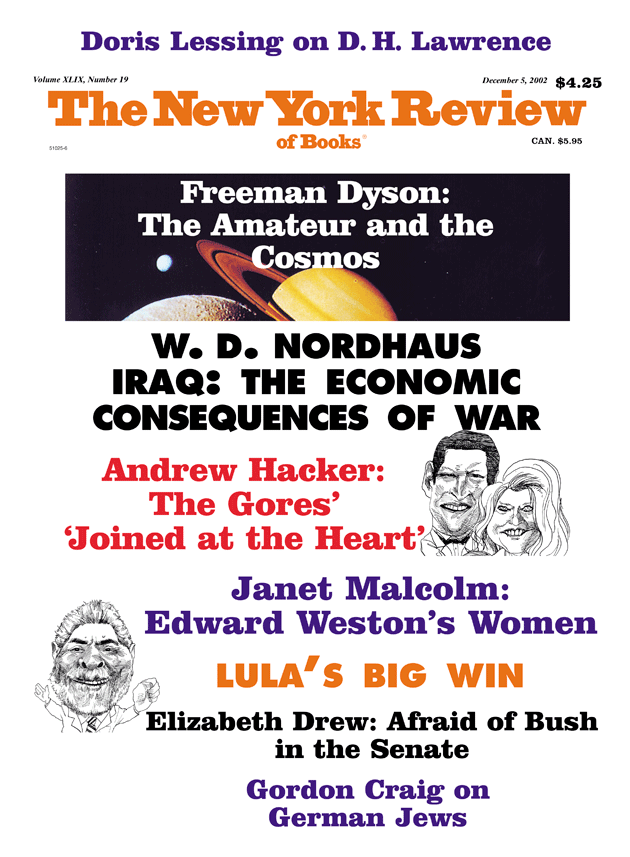

This Issue

December 5, 2002