To the Editors:

Herod [the Great] was, on balance, a good king…. Herod was a good king, on balance…. On balance, [Herod] Antipas was a good tetrarch…. Antipas was on the whole a good ruler…. Joseph Caiaphas [the High Priest]… was a success…. Caiaphas was pretty decent.

—E.P. Sanders, The Historical Figure of Jesus, pp. 19, 21, 27, 93, 265

E.P. Sanders’s confused presentation of Excavating Jesus [“Who Was Jesus?” NYR, April 10] is suffused with the acrid stench of burning straw. It also contains basic misunderstandings of our position on Jesus, Judaism, and the Roman Empire, that is, on most everything in our book.

On Jesus. Scholarship is still divided on whether Jesus’ “Kingdom of God” was exclusively future, exclusively present, or already present but not yet fully consummated. Sanders chooses that first option and we choose the third but focus within it on that already present element. Whatever Jesus said about the future was flatly wrong—any imminent consummation is now two thousand years and still counting. But, since Christianity did not slowly fade away, it must have held something else besides erroneous future predictions. Our book focused deliberately on that something else. It is, by the way, rather scurrilous to suggest that we avoid, for example, “the Son of Man…because it is crass, lurid, ancient, too Jewish, and wrong.” Given that we locate Jesus in a thoroughly Jewish context throughout our book, “too Jewish” is not only straw but cheap straw at that.

Sanders says that we make Jesus into a “socioeconomic reformer” by stressing “Jesus’ economic program.” But Jesus’ program was totally political and economic but also totally religious and theological (“Kingdom/of/God”). It suggests how the world would be if God sat on Caesar’s throne—here below upon this present earth. Pilate did not consider Jesus a violent threat or he would have crucified his closest companions beside him. But he considered him an opponent of Rome’s program and he decreed legal, official, and public execution. From his own point of view, Pilate got it precisely right. (Mrs. Pilate, of course, got it righter: “Have nothing to do with Jesus.”)

On Judaism. Sanders mistakenly equates Galilean “Hellenization” with Galilean “Romanization.” But the former is a matter of culture, the latter is a matter of power. Neither of us ever described the cities of Lower Galilee as primarily, predominantly, or exclusively within Hellenistic as distinct from Jewish culture and religion. But we emphatically described those places as being within Roman as distinct from Jewish control and power. Even the suggestion that there were Greco-Roman Cynics in Sepphoris—not found anywhere in Excavating Jesus, by the way—could never be construed as asserting that city let alone all of Galilee to be non-Jewish (except as straw argumentation). Both of us speak consistently of “Roman Galilee” but never meaning Galilee as demographically, culturally, or religiously Roman but always as imperially, economically, and politically Roman. Furthermore, Sanders mischaracterizes our discussion of Jewish purity rituals as amounting only to resistance, which he attributes to our (hidden, implied, but never articulated) view of a direct pagan occupation of Israel.

On the Roman Empire. Sanders says that “the model that seems always to have been in Crossan’s mind when discussing Jesus is that of Ireland, his own country, which the British conquered and colonized, exploiting the indigenous population” (p. 51). But, precisely on this point, two of Sanders’s comments cancel one another so obviously that their dual presence is more willfully obtuse than thoughtfully critical. If Crossan, or anyone else, uses an analogy between first-century Jewish/Roman and nineteenth-century Irish/British history, they would know that in both cases culture and religion remained utterly and irrevocably Jewish or Irish even while control and rule were utterly but not irrevocably Roman or British.

There is a final irony to Sanders’s review. Scholars of early Christianity have always criticized his refusal to use source-analysis in studying the gospels. Yet his review consistently applies a kind of source-criticism to our book that distinguishes Crossan’s exegetical views (or alleged former views) from Reed’s archaeological descriptions. For the record, Excavating Jesus was a collaborative effort, and we both stand fully behind each chapter, even though in the process we debated, disagreed, compromised, and negotiated. That process was always an honest and exhilarating exchange of ideas in the best scholarly tradition. Sanders’s review, on the other hand, is not in that tradition.

John Dominic Crossan

De Paul University

Chicago, Illinois

Jonathan L. Reed

University of LaVerne

LaVerne, California

E.P. Sanders replies:

The reader of the authors’ letter would have no idea of the principal points of their book or of the review, which is a shame, since they deserve consideration. I shall, however, reply only to their comments.

On Jesus. It is true that many scholars think that some aspects of Jesus’ proclamation of the kingdom of God applied, in his own intention, to the present. But this generally accepted view should not be allowed to obscure the fact that the Jesus of Crossan and Reed speaks only about the present, and then about very few matters. In their book, Jesus’ proclamation that in the future God would intervene in the world disappears almost without a trace. Their letter offers a reason for the disappearance: it was “flatly wrong.” That is no reason for the historian to avoid it. Doing so is bad history, since later generations would not have invented predictions that did not come to pass. If Jesus said it, we should take it into account. Moreover, ignoring the future predictions reduces Jesus’ burning idealism, which he seems to have based on his future expectation.

Advertisement

All that is left to the Jesus of Crossan and Reed is a supposed attempt on Jesus’ part at socioeconomic reform—which also failed! I stressed this aspect of their book because it gets far more pages than any other part of Jesus’ message. The few other topics that are mentioned in their book appear very briefly. In their presentation, Jesus deliberately confronted Herod Antipas (and thus Rome, which stood behind him) with an alternative economic policy, based on free food, which finally led to his execution. As the authors’ letter states, in their view Jesus thought that he was fulfilling God’s will. This is another generalization that is not in dispute. The question is whether or not they have found a credible point of opposition between Jesus and the ruling powers: in their view, he advocated free food instead of a commercial system that arranges for the distribution of food in exchange for money. The review indicates that I did not find this hypothesis persuasive.

On Judaism. The authors seem to have missed the contrast, strongly emphasized in the review, between Crossan’s earlier view of cultural Hellenization and Crossan and Reed’s present view of Romanization, consisting largely of urbanization and commercialization. I welcomed the fact that Hellenization has now been dropped, but I regretted the inaccurate way in which they presented “Romanization.” In their book they do not describe Roman power in Galilee, but rather Antipas’ supposed Romanization of the economy by introducing commerce.

Since most of the book depicts Jewish Palestine as lacking an appreciable Gentile population (in contrast to Crossan’s earlier books), I thought it worth noting that the assumption of a strong Gentile presence sometimes slips back in. The letter claims that I presented their view that the Jews of Galilee lived in the midst of “direct pagan occupation” as “hidden, implied, but never articulated”—thus implying that it was I who introduced the topic. In reality, I wrote that the assumption of Gentile occupation appears sporadically. In the book they wrote that “Jewish individuals and groups emphatically maintain external rituals of bodily purification distinct and different from those of the pagans who surround them, interact with them, and rule over them” (p. 139); and they referred to Jewish “resolve and determination to stand up to Roman might and occupation” (p. 161, emphasis added). Elsewhere, they recognize that Rome did not occupy Palestine, but old views die hard.

On the Roman Empire. In the review I noted Crossan’s use of the model of the British Empire in Ireland in an effort to explain why the present book continues to refer to Jewish Palestine as a “colony” (pp. 188, 201), as “occupied” by Romans (p. 161), and as containing cities planted by Rome (p. 272), although elsewhere (p. 187) the authors recognize that Rome did not colonize Jewish Palestine and did not found a city there until approximately one hundred years after the death of Jesus. One sees here as elsewhere two views side by side. One is presumably the “old” Crossan, still clinging to the notion of a Gentilized Galilee and (I suggested) thereby revealing the influence of the British colonization of Ireland. The other view is presumably that of Reed, who knows when Rome in fact put its first city in Palestine. There is no objection to using another empire to illustrate a point, but the analogy with Ireland has consistently misled Crossan, and some fragments of that model remain in the present book.

Final irony. My “refusal to use source-analysis” may be an insider’s joke. I have written extensively about the sources of the gospels, but I reject Crossan’s opinion that the Gospel of Thomas is very ancient and that the layers of a hypothetical (and, in my view, fictional) document, Q, can be reconstructed. These dubious hypotheses lie at the heart of his “source-analysis.” I am joined by most scholars in the first rejection and by a good number in the second.

Advertisement

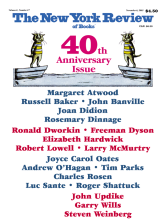

This Issue

November 6, 2003