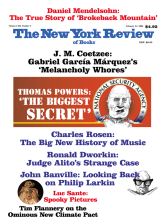

T.S. Eliot observed toward the end of his life that he could not be called a great poet because he had not written an epic. This was a sly piece of false modesty on the part of Old Possum, implying as it did that had he turned his pen to the epic form he would of course have been up there with Homer, Virgil, and Dante. His stricture also served, backhandedly, to withhold greatness from other poets of what he thought of as his culturally debased time, such as Yeats and Wallace Stevens. In the Age of Prose, Eliot was saying, even the finest poet can be expected to manage no more than the small thing. To all this Philip Larkin would likely have answered with his accustomed epistolary expletive: bum.1

Larkin had the reputation of being the most costive of artists. In his writing lifetime—from the late 1930s until the middle of the 1970s, when the muse left him, returning only for brief and infrequent trysts—he published five short volumes of verse, with long intervals of silence between each appearance. Of these volumes he considered The Less Deceived (1955), The Whitsun Weddings (1964), and High Windows (1974) to contain the totality of his mature work. In those three and a half decades, however, he also produced two novels, Jill and A Girl in Winter, as well as a large body of essays, reviews, and occasional pieces which were collected as All What Jazz (1970), Required Writing (1983), and the posthumous Further Requirements (2001).

He also edited The Oxford Book of Twentieth-Century English Verse (1973), which he labored on happily for some seven years—he really did love libraries, and was probably most at ease within their tranquil confines—which was a great success with the reading public, and which brought its editor considerable royalties. Then, in 1988, three years after the poet’s death, his friend and literary coexecutor, Anthony Thwaite, brought out the Collected Poems. Although Thwaite was widely criticized for printing the poems in chronological order, which some regarded as no order at all, the volume was a revelation. Who would have thought the man had so much poetry in him?

And it was not merely that Thwaite had uncovered a cache of inspired juvenilia, although there was a lot of that—the editor put a “substantial selection” of this work, including the contents of Larkin’s first published collection, The North Ship, in a separate section, “Early Poems 1938–45,” at the back of the volume2—but that there were so many poems Larkin had left unpublished—sixty-one in the section of mature poems and twenty-two in that of early work. From this material Larkin might have assembled a further, fat, volume, one which a poet who was less a perfectionist than he would have been proud of. Indeed, in the case of a handful of these poems it is hard to know the reason for their suppression; the fact that they were withheld is in itself an indication of Larkin’s confidence and scrupulousness as a poet.3

Thwaite must have anticipated criticism of the Collected Poems of 1988, for in his introduction to that volume he writes:

To have added so many unpublished poems, from the flood at the beginning to the trickle towards the end, together with many others which he published in his lifetime but chose not to collect, is something I do not take lightly. Philip Larkin’s own precise wishes in his will, drawn up during his illness in July 1985 [he was to die at the beginning of December that year], were not at first entirely clear; yet he certainly gave his literary executors, of whom I am one, discretion over the publication of his unpublished manuscripts.

Before he died Larkin had instructed his lover Monica Jones that his diaries should be destroyed. Monica called on another of Larkin’s lovers, his former secretary Betty Mackereth, to perform the task. Betty took the thirty-odd volumes into Larkin’s office in the Brynmor Jones Library at Hull University and fed them page by page into a paper shredder—the task took all afternoon. With characteristic loyalty and discretion, she did not attempt to read the diaries before destroying them, “but I couldn’t help seeing little bits and pieces. They were very unhappy. Desperate, really.”

Larkin had told his future biographer Andrew Motion, “When I see the Grim Reaper coming up the path to my front door I’m going to the bottom of the garden, like Thomas Hardy, and I’ll have a bonfire of all the things I don’t want anyone to see”; however, the bonfire was never built, and according to Motion, the diaries, “eight manuscript books in which he drafted his poems, and the large mass of his unpublished papers and letters lay undisturbed in his house when he was carried out of it for the last time.”

Advertisement

Larkin’s directions on what was to be done with these surviving papers were hard to interpret, and the clauses in his will dealing with the matter were ambiguous. Andrew Motion—he was another of the poet’s three literary executors, the third being Monica Jones—tells us that a lawyer was consulted about how Larkin’s wishes in regard to posthumous publication should be interpreted. The lawyer declared the will “repugnant,” that is, contradictory. This finding cleared the way for the executors to authorize publication of what among the papers they considered valuable, citing what Larkin himself had said in a talk on preserving contemporary manuscripts, delivered in his role as head of a major university library: “Unpublished work, unfinished work, even notes towards unwritten work, all contribute to our knowledge of a writer’s intentions.”4 It is appropriate that we have Larkin’s chronic indecisiveness allied with his diligence as a librarian to thank for the preservation of so many superb unpublished poems, and his marvelous but controversial letters, a hefty selection of which, again edited by Anthony Thwaite, was published in 1992.

Thwaite obviously was stung by the criticism, mainly from academics and scholars, of the Collected Poems of 1988, and in 2003 brought out another version, dropping many of the unpublished poems and the juvenilia, and eschewing the chronological method. In his introduction to the later volume he writes that its predecessor “showed the growth of a major poet, testing, filtering, rejecting, modulating, achieving”:

This new edition of Philip Larkin’s poems is partly a considered response to suggestions that what was needed, too, was a book that followed Larkin’s own deliberate ordering of his poems in each successive book (“I treat them like a music-hall bill: you know, contrast, difference in length, the comic, the Irish tenor, bring on the girls”)….

The 2003 Collected Poems, then, is not intended as a corrective or a replacement of the earlier book, but as a sort of companion volume. This is an odd arrangement, and one wonders what Larkin the librarian would have made of it. Would he have been flattered, amused, reprehending? One can imagine a tag line in a letter to his pal and confidant Kingsley Amis: “Two Collected Poems bum.”

Just as he encouraged the misconception that he had produced a meager body of work, so too did Larkin seek to present himself before the public in the disguise of a bluff, no-nonsense Englishman who just happened to produce now and then, by happy accident, as it were, an exquisite small volume of poetry.5 He refused to live the literary life of readings and lectures and college residencies—“I don’t want to go around pretending to be me”6—and professed to be embarrassed by the fame which came to him in his middle years. This was not entirely a pose, although despite his image in the press he was no recluse, and at Brynmor Jones Library at Hull ran a large staff with skill and authority.7 He was, however, an insecure and deeply troubled man, selfish, calculating, essentially solitary—“I see life more as an affair of solitude diversified by company than an affair of company diversified by solitude”—and a womanizer who was at once predatory and timorous. He was also loving, gracious, loyal in his fashion, and hilariously funny.

It is possible to venture these character assessments on the evidence Larkin left behind in his copious correspondence. In some quarters that evidence is regarded as evidence for the prosecution. Certainly much of what he wrote in the letters was incriminatory, as is commonly the case, if the letter writer has been honest. Larkin’s views on politics, race, and class, as expressed in the correspondence, especially in his later years, are frequently hair-raising in their violence and virulence. They are also in many instances extremely funny, if appallingly so. Larkin’s latest biographer, Richard Bradford, gives a representative sample of the kind of things with which Larkin the letter-writer sought to amuse his friends:

He complained to [Kingsley] Amis in 1943…that “all women are stupid beings” and remarked in 1983 that he’d recently accompanied Monica [Jones] to a hospital “staffed ENTIRELY by wogs, cheerful and incompetent.” …His views on politics and class seemed to be pithily captured in a ditty he shared again with Amis. “I want to see them starving,/The so-called working class,/Their wages yearly halving,/Their women stewing grass…” For recreation he apparently found time for pornography, preferably with a hint of sado-masochism: “…I mean like WATCHING SCHOOLGIRLS SUCK EACH OTHER OFF WHILE YOU WHIP THEM.”8

Although it is not much of a defense, one might say of Larkin that he was the victim of what our teacher-priests used to call “bad companions.” Richard Bradford points out that “virtually all indications that Larkin was a misogynistic, intolerant racist occur in his letters to Colin Gunner and Kingsley Amis.” Amis, who was as funny as Larkin, early on abandoned his youthful socialist convictions in favor of a kind of radical low Toryism which swelled with the years to caricature proportions; Gunner, whom Larkin had not seen since their schooldays together, renewed contact with him in 1971, and the two embarked on a correspondence in which each shored up the other’s baleful right-wing leanings. “Gunner,” Bradford writes, “was the kind of eccentric Englishman one might expect to find in fiction but who frequently survives outside it: lower middle class, quixotic and reactionary, and almost endearingly self-destructive.”

Advertisement

2.

When Anthony Thwaite’s fat volume of Larkin’s letters appeared in 1992 it opened the door for “a rush of dunces,” as the critic Clive James has observed.9 Literary London was particularly agitated. Bradford quotes the poet and academic Tom Paulin writing in the TLS that he found the letters to be “a distressing and in many ways revolting compilation which imperfectly reveals and conceals the sewer under the national monument Larkin became.” Lisa Jardine, a professor in the English department at the University of London, wrote, Bradford tells us, that while she “would not go quite so far as to ban the study of Larkin his poems would be removed from the core curriculum and dealt with only to disclose ‘the [parochial] beliefs which lie behind them.’…”

As well as slightly misquoting Jardine, Bradford may be overstating matters—at no point does the professor even hint at a desire to ban Larkin’s work. Yet her 1992 article, the brave new multicultural worldism of which is already outdated, has sinister undertones. A cool anathema by a hot-eyed zealot, it varies in tone between that of the ineffable Miss Pratt, head of Beardsley School in Nabokov’s Lolita—whose school “does believe very strongly in preparing its students for mutually satisfactory mating and successful child rearing”—and of a Ministry of Culture spokeswoman in one of those hopeless pre-1989 Soviet Bloc satellites.

She dismisses the poems—“Actually, we don’t tend to teach Larkin much in my Department of English”—for not engaging with “everyday discriminations, everyday assumptions of white British superiority” and for the fact that the values she thinks he celebrates sit uneasily “within our revised curriculum, which seeks to give all of our students, regardless of background, race or creed, a voice within British culture.” By this criterion, much of the work of Shakespeare, to name but one dead white British male, would be banished from the curriculum. She closes her polemic by declaring that “for the sake of the new, forward-looking, plural and multicultural British nation, we must stop teaching the old canon as the repository of authentically ‘British values’ and as a monument to a precious ‘British way of life.'” One thinks immediately of that famous photograph of Larkin taken by Monica Jones in 1962 at Coldstream on the Scottish–English border; the poet is seated by a stone marker bearing the legend ENGLAND over which, just before the picture was taken, he had, according to Jones, urinated. So much for the “British way of life.”

Clive James, discussing the reaction to the letters by the London-based black American playwright Bonnie Greer—“In her view, there was no need to worry about Larkin the racist, because Larkin the poet was not very good anyway”—states the case with his accustomed grace and succinctness, though it is not entirely a case for the defense:

Philip Larkin really was the greatest poet of his time, and he really did say noxious things. But he didn’t say them in his poems, which he thought of as a realm of responsibility in which he would have to answer for what he said, and answer forever. He also thought there was a temporary and less responsible realm called privacy. Alas, he was wrong about that. Always averse to the requirements of celebrity, he didn’t find out enough about them, and never realized that beyond a certain point of fame you not only don’t have a private life any more, you never had one.10

Bradford’s biography is a competent if somewhat pedestrian and in places sketchy affair. The author is professor of English at the University of Ulster, and has written, among other things, a biography of Kingsley Amis. On the very first page of First Boredom, Then Fear one’s trust in his authority in the matter of Larkin’s work, if not his life, is shaken when he quotes Seamus Heaney writing of Larkin’s as the “not untrue, not unkind” voice of postwar England and fails to recognize that Heaney is quoting from Larkin’s poem “Talking in Bed.”11

Bradford’s initial intention seems to have been to erect a spirited defense of Larkin against those who would confuse the politics of the man with the aesthetics of the artist, and in his opening pages he curls a disdainful lip at Paulin, Jardine, et al., but soon he is dismissing the pro-Larkinists as well, writing that to claim that “a writer’s prejudices are separable from and irrelevant to their [sic] literary achievement, is charitable but both demonstrably invalid and impossible to maintain.” His preferred defense is to point to Larkin’s myriad-mindedness:

He played different roles for different people. The personae selected for particular scrutiny and condemnation are, post-1992 [the year the Letters were published], the ones which accord with the image of him as a loathsome archetype of Englishness. There are many others, and all are curious combinations of candour, exaggeration and self-parody. Just as significantly, why should we assume that our appreciation of his poems will be tarnished by our knowledge of Larkin as alien from our, in Martin Amis’s words, “newer, cleaner, braver, saner world.”

Rereading the letters now, one finds it difficult to see why at the time of publication so much was made of the misogynistic and misanthropic aspects of them. Larkin had never sought to hide his views, though as might be expected his expression of them in public was far milder than in the correspondence. Anyone who reads his poems “Vers de Société”12 or “Homage to a Government” or “Take One Home for the Kiddies” will be left in little doubt about Larkin’s views on society, politics, and the human—and animal—condition. In interviews he delighted in disappointing his interviewers’ liberal expectations of what “a poet” should be and think and profess: “I’ve always been right-wing. It’s difficult to say why, but not being a political thinker I suppose I identify the Right with certain virtues and the Left with certain vices. All very unfair, no doubt.”

In Bradford’s terms, what Larkin is presenting here is the acceptable—depending on your politics—face of the Little Englander who loves cricket and warm beer and distrusts change and foreigners. The same face can frequently be glimpsed peering out from the poems, but there it wears an impish and highly ironical smile—has there ever been a funnier serious poet than Larkin?—while in the letters the smile is turned into a leer so horrible that it seems less the grimace of a bigot than a mischievously fashioned Halloween mask.

Perhaps the single most shocking revelation in the published correspondence comes in a throwaway admission in a letter to another friend, the historian Robert Conquest. Larkin had been commissioned by the Countess of Dartmouth, head of a government working party set up to report on “The Human Habitat.” The result was “Going, Going,” an elegy for all that would soon be lost of the England that the poet claimed to love—“The shadows, the meadows, the lanes/The guildhalls, the carved choirs”—which the committee, when the poem was delivered, found too strongly expressed for its taste. After the poem’s publication a report appeared in the satirical magazine Private Eye to the effect that the countess had prevailed upon Larkin to cut a particularly biting stanza, a request to which Larkin had acceded. Larkin hotly denied the cut. However, in a letter to Conquest on May 31, 1972, Larkin writes:

Have you seen this commissioned poem I did for the Countess of Dartmouth’s report on the human habitat? It makes my flesh creep. She made me cut out a verse attacking big business—don’t tell anyone.

The offending lines13 were quietly restored when the poem was published in the volume High Windows—but still.

3.

Although Bradford seems intent on providing a corrective to Andrew Motion’s Philip Larkin: A Writer’s Life, he too, like Motion before him, grows increasingly pursed of lip as his narrative progresses. Bradford’s book is far less detailed than that of his predecessor, but it does place welcome emphases on matters that Motion for all his comprehensiveness glided over perhaps too lightly. In particular, Bradford’s portrait of Larkin’s father is far more interesting and, one suspects, more fair, than Motion’s. Sydney Larkin, an accountant by profession, was a remarkable man, a self-righteous authoritarian and a keen admirer of the Nazis—he kept on the mantelpiece in the family home a miniature statue of Hitler which made a Nazi salute when a button was pressed, which reminds one of Philip’s giving pride of place on his desk at Hull to a framed photograph of Guy the Gorilla. But Larkin père was also a man of culture and wide reading who encouraged his son’s literary bent.

Larkin did seem to feel uneasiness when the subject of his father was raised, and in a 1979 interview, for instance, he was purposely bland: “My father was keen on Germany for some reason: he’d gone there to study their office methods and fallen in love with the place.” Larkin’s mother was a highly strung and somewhat unstable person, to whom nevertheless he was devoted throughout her long life. In Motion’s book there is a remarkable photograph of Eva Larkin circa 1970, sitting relaxedly in an armchair over the back of which her son leans, wearing a look of mingled animosity, defensiveness, and desolation; on the reverse of the picture Larkin had written: “Happy As the Day is Long.”

By now Larkin’s life story is well known. He was born in Coventry in 1922, the second of two children14 ; the delivery was nearly a month late, the baby weighed almost ten pounds, and, ironically, in view of Larkin’s later emblematic baldness, “had luxuriant black hair.” As a boy he was cripplingly shy, and had a bad stammer which stayed with him until he was well into his thirties.15 After schooling in Coventry he went to Oxford, where he was unhappy until he met fellow student Kingsley Amis, whose jokes and impersonations lightened his days, but whose forceful personality and high ambition oppressed him, according to Bradford.

Larkin started out as a novelist, and had written two novels by the time he was twenty-five. However, the enormous, instant success of Amis’s Lucky Jim (1954), which took at least some of its inspiration from the author’s friendship with Larkin, seems to have discouraged Larkin so comprehensively that he abandoned his ambitions to go on writing fiction and turned to poetry instead. In 1982 he told The Paris Review: “I wanted to ‘be a novelist’ in a way I never wanted to ‘be a poet,’ yes. Novels seem to me to be richer, broader, deeper, more enjoyable than poems.” From the start, then, the act of making poetry was for Larkin tainted with the bitter taste of failure, which makes his poetic triumph all the more remarkable. Or does it? As he famously declared, “Deprivation is for me what daffodils were for Wordsworth.”

He became a librarian almost by chance. In his account of it, the war was on and

I was sitting at home quietly writing Jill when the Ministry of Labour wrote to me asking, very courteously, what I was doing exactly. This scared me and I picked up the Birmingham Post and saw that an urban district council in Shropshire wanted a Librarian, so I applied and got it.

After the grim years in deepest Shropshire he moved to another grim location, when in 1950 he secured a position as under-librarian at Queen’s University in Belfast. If Larkin ever “found” himself, then it was in Belfast, of all places, that the happy discovery was made.16 He was temporarily free of his family, and among the college staff he made friends who opened for him new vistas of freedom and fulfillment. In particular he was taken with Patsy Strang, née Avis—later she would marry the poet Richard Murphy—the wife of a lecturer in the philosophy department. Larkin was fascinated, Motion writes, by the “food- providing, drink-pouring, dog-loving, occasionally pipe-smoking ‘tall, rather gawky brunette’ Patsy Strang,” and they embarked upon an affair which, one surmises, offered Larkin his first real glimpse of what could be had beyond the spiritual and sensual limits which his background, and his own cramped personality, had imposed upon him.

Patsy was one of the many women whom Larkin depended upon, or exploited, including Monica Jones, his most enduring love, who at various times had to share him with Maeve Brennan, Larkin’s colleague at Hull, and his secretary Betty Mackereth. Larkin vacillated between his women, lying to all of them, as he ineptly sought to conceal from each of them his true feelings for the others. It is hard not to judge him harshly for his behavior in these affairs of the heart, but the evidence remains that all of his women, no matter how badly he treated them, remained loyal and loving to the very end—when he was dying, of cancer of the esophagus, they would sometimes encounter each other at his bedside17—which is surely a testament to his worth as a man, for these were strong, self-respecting women who saw him for what he was, and accepted it.

All this, of course, is incidental to what matters, which is the poetry. We do not judge Shakespeare’s plays because he willed to Anne Hathaway his second-best bed, or Gesualdo’s music because he murdered his wife. In time, when the dunces have been sent back to their corners, what will remain is the work. For all his careful posing as the homme moyen, Philip Larkin was a poet to the tips of his nerves. When the muse virtually deserted him in the mid-1970s—he wrote only a handful of poems after those collected in High Windows, published in 1974, although that handful included his final masterpiece, “Aubade”—he made light of it, saying that he had lost the ability to write poems in the same way that he had lost his hair, but in reality he was devastated, and much of the pain and rage of his final decade is surely directly attributable to this loss. Probably no one in that dunces’ corner appreciates the ghastliness of the predicament of an artistic genius who can no longer produce art. There was much ugliness in Philip Larkin’s character, but what mattered most to him was beauty, and the making of beautiful objects. In this lay his greatness.

And, pace Eliot, Larkin was—is—a great poet. Poems such as “The Whitsun Weddings,” “Show Saturday,” “The Old Fools,” “Church Going,” these are the epics of our time. Yet for anyone who has not yet read this wonderful poet, it might be best to begin not on those peaks, but with, for example, the tiny poem “Cut Grass,” one of the most nearly perfect lyrics in the language, plangent with the sense of summer’s loveliness and the finality of dusty death:

Cut grass lies frail:

Brief is the breath

Mown stalks exhale.

Long, long the death

It dies in the white hours

Of young-leafed June

With chestnut flowers,

With hedges snowlike strewn,

White lilac bowed,

Lost lanes of Queen Anne’s lace,

And that high-builded cloud

Moving at summer’s pace.

Or the heartbreakingly tender “Faith Healing,” a poem that no true misogynist could have written:

Slowly the women file to where he stands

Upright in rimless glasses, silver hair,

Dark suit, white collar. Stewards tirelessly

Persuade them onwards to his voice and hands,

Within whose warm spring rain of loving care

Each dwells some twenty seconds. Now, dear child,

What’s wrong, the deep American voice demands,

And, scarcely pausing, goes into a prayer

Directing God about this eye, that knee.

Their heads are clasped abruptly; then, exiled

Like losing thoughts, they go in silence; some

Sheepishly stray, not back into their lives

Just yet; but some stay stiff, twitching and loud

With deep hoarse tears, as if a kind of dumb

And idiot child within them still survives

To re-awake at kindness, thinking a voice

At last calls them alone, that hands have come

To lift and lighten; and such joy arrives

Their thick tongues blort, their eyes squeeze grief, a crowd

Of huge unheard answers jam and rejoice—

What’s wrong! Moustached in flowered frocks they shake:

By now, all’s wrong. In everyone there sleeps

A sense of life lived according to love.

To some it means the difference they could make

By loving others, but across most it sweeps

As all they might have done had they been loved.

That nothing cures. An immense slackening ache,

As when, thawing, the rigid landscape weeps,

Spreads slowly through them—that, and the voice above

Saying Dear child, and all time has disproved.

This Issue

February 23, 2006

-

1

British slang for buttocks. Asked in an interview if he had ever attempted a truly long poem, Larkin answered: “A long poem for me would be a novel. In that sense, [his novel] A Girl in Winter is a poem.”

↩ -

2

The early efforts are much as one would expect of a fledgling poet, with many “o’er’s” and “twas’s” and the inevitable inversions—”footsteps cold,” “the night/Impenetrable”—but here and there the voice speaks out in sudden authority, as in the closing line of this fragment from the very first poem in the section, “Winter Nocturne,” written when Larkin was sixteen:

↩ -

3

For example, two poems on the same subject, “Autumn,” from October 1953, and “And now the leaves suddenly lose strength,” November 1961; “Ape Experiment Room,” February 1965; the beautiful “Morning at last: there in the snow,” February 1976; “Long lion days,” July 1982, as good in its way as the published “Days” or “Solar”; and this spirited jeu d’esprit, as Anthony Thwaite dubs it:

↩ -

4

In a “Statement” published in Poets of the 1950s, edited by D.J. Enright, Larkin had written: “…I think the impulse to preserve lies at the bottom of all art.”

↩ -

5

In an interview with the London Observer he did confess, with typically subversive humor, to being pleased when he managed to finish a poem, “as if I’ve laid an egg, and even more pleased when I see it published.”

↩ -

6

This was in the Observer interview, where he also gave his famous answer to a question about foreign travel: “I wouldn’t mind seeing China if I could come back the same day.”

↩ -

7

“My job as University Librarian is a full-time one, five days a week, forty-five weeks a year. When I came to Hull, I had eleven staff; now there are over a hundred of one sort and another. We built one new library in 1960 and another in 1970, so that my first fifteen years were busy” (Paris Review interview, 1982).

↩ -

8

In fact, he did not “apparently” find time for pornography, but was an unabashed enthusiast for the stuff, and kept a hoard of hard-core magazines, some of them meant for a homosexual readership, in a file drawer in his office and also, it seems, under his bed at home.

↩ -

9

Clive James, The Meaning of Recognition: New Essays 2001–2005 (Picador, 2005).

↩ -

10

It is worth staying with James a moment longer. He goes on to say that to treat properly the question of the artist’s right to privacy against his public responsibility, that question would need to be raised in class. “Ideally it would be a literature class in which race relations might occasionally be discussed, but the rule of dunces may soon ensure that it will be a race relations class where literature is occasionally discussed, and only as evidence for the prosecution.”

↩ - 11 ↩

-

12

Which opens thus:

↩ - 13 ↩

-

14

His sister, Catherine (Kitty), is largely ignored both by Motion and Bradford; if she is anything like Larkin, she is probably glad to have been passed over.

↩ -

15

“Until I grew up I thought I hated everybody, but when I grew up I realized it was just children I didn’t like. Once you started meeting grown-ups life was much pleasanter. Children are very horrible, aren’t they? Selfish, noisy, cruel, vulgar little brutes.”

↩ -

16

Returning to England in 1955 he wrote, in the significantly titled poem “The Importance of Elsewhere,” of his nostalgia for Belfast’s

↩ -

17

Maeve Brennan, in her memoir The Philip Larkin I Knew, wrote of visiting him one day in hospital at the same time as Monica Jones: “Philip reached out to me in a passionate embrace. Deeply embarrassed I froze under the hostile stare of Monica, who was sitting on the opposite side of the bed.”

↩