Amitav Ghosh, an Indian anthropologist, historian, and novelist who lives and teaches in New York and India, is the author of ten books. His new novel, Sea of Poppies, which is the first in a projected trilogy and has been shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, is set in India in 1838, in the days leading up to the Opium Wars. Ghosh tracks the lives, and the language, of an unlikely collection of men and women—princes, sailors, merchants, pirates, peasants, and runaway girls—all of whom eventually converge on an American schooner called the Ibis.

It is a rollicking tale, or rather collection of tales—politically forceful, historically fascinating, and rarely subtle. Ghosh may not be a stylistically exciting writer, sentence for sentence, and the discipline and freshness of his earlier, less extravagant books seem to have been abandoned; nevertheless, this new work is a linguistic triumph. For if the prose is sometimes commonplace, the dialogue never is. Ghosh has taken all of his considerable historical knowledge and passion and funneled it into the language of his characters. They themselves may occasionally fail to come completely to life, but their words are alive. Ghosh has given to each of the many disparate characters a patois, an idiom, a poetry that is utterly irresistible. The novel presents itself as a tale of opium and pirates and cruelty and love, but at its best, Sea of Poppies is a celebration of language—its idiosyncrasies, its prejudices, its humor, cruelty, freedom, and, finally, its generous, open-armed invitation to escape.

The novel begins with Deeti, a young woman from a small village in the northern Bihar province of India. While splashing in the Ganges with her six-year-old daughter, Deeti, who has never seen the sea or any of its vessels, has a vision of a great ship with two triangular sails and a figurehead in the shape of a graceful, curved-beaked bird. She rushes from the river to her own tiny shrine where she draws a quick, crude picture of the ship to add to a collection of family relics and religious statues.

At this same moment, four hundred miles away, where the Ganges meets the Bay of Bengal, the Ibis, a schooner with a “carved head of a bird that held up the bowsprit,” has dropped anchor. Deeti’s supernatural vision feels like an almost obligatory nod to the magical realism many have come to expect from the postcolonial novel, because Ghosh quickly leaves it behind for a far different kind of miracle, one that he is clearly much more interested in: the brilliant tangle of Indian culture that grew in spite of, and because of, Southeast Asia’s history under the imperial rule of Britain.

The title of the novel refers to the waving fields of white flowers that rolled over nineteenth-century India. Deeti, and villagers and farmers throughout the region, are forced, first by the British East India Company and then by the imperial government itself, to cultivate poppies for the opium trade. In 1838, in their attempt to right the balance of trade between China and Britain, the British were illegally selling about 1,400 tons of opium to China per year. Those 1,400 tons were grown and harvested and packed in India and shipped on vessels like the Ibis. Having notoriously turned China into a country of opium addicts, the British also, in a less familiar but equally lucrative and destructive part of their trade policy, turned India into a country of opium suppliers and themselves into the largest drug dealers in the world. Chinese attempts to block the importation of opium, which led to the Opium Wars, are one side of the story. In Sea of Poppies we find Indian farmers, traders, sailors, and investors caught up in the enormous wave of opium-fueled nineteenth-century imperial greed. They are all part of another side of the same sorry history.

For Deeti, in her poor village, opium permeates every moment of life. Her hut needs a new roof, but there is no thatch to repair it: the fields that once grew wheat and straw are now filled with “plump poppy pods.” (Vegetables, too, have been displaced by the opium crop. The British “would allow little else to be planted; their agents would go from home to home, forcing cash advances on the farmers…. If you refused they would leave their silver hidden in your house, or throw it through a window.” At the end of the harvest, the profit to the villagers would come to just enough to pay off the advance.) Her husband, who works in the opium factory, is an opium addict. She discovers this on her wedding night, when he blows opium smoke into her mouth and allows his brother to rape her unconscious body because he is incapable of performing his conjugal duties. The father of her child, she comes to realize, is “her leering, slack-jawed brother-in-law.”

Advertisement

Deeti’s husband is a victim of the British two times over: a sepoy who served them in campaigns overseas, crippled by his battle wounds, he has turned to opium for the pain, which has crippled him further. “You should know,” he tells Deeti of his cherished opium pipe, “that this is my first wife. She’s kept me alive since I was wounded: if it weren’t for her I would not be here today. I would have died of pain, long ago.” Ghosh’s description of the opium factory where Deeti’s husband works is terrifying: it oozes and roars with ominous horror, a sickly, sluggish inferno. Opium is literally the air Deeti breathes: “The sap seemed to have a pacifying effect even on the butterflies, which flapped their wings in oddly erratic patterns, as though they could not remember how to fly.”

When Deeti’s husband dies, she is forced to set out on a dangerous journey that eventually leads her to the Ibis, the ship she saw in her vision. In fact, the Ibis is the improbable fate of all the major characters, a magnet powered by the opium trade that attracts victim and oppressor alike. A schooner from America, the Ibis began its life as a “blackbirder” for transporting slaves. Not fast enough to escape the American and British ships that, following the formal abolition of the slave trade, now patrol the West African coast, the Ibis has come to India on a new mission. “As with many another slave-ship, the schooner’s new owner had acquired her with an eye to fitting her for a different trade: the export of opium.”

For Ghosh, the Ibis exists not only to unite his incongruent characters on their journey into diaspora. It is also a symbol of the India, and indeed the world, that readers of some of his earlier work will recognize—a world composed of human needs and desires, of aspirations and betrayals, all of them historically, geographically, morally, and inextricably linked. Ghosh’s India could never fit on a map; it requires a globe, a spinning three-dimensional sphere extending in every direction at once, where every path circles back to its starting point.

The second mate on the Ibis is a handsome twenty-year-old with curling black hair from Maryland named Zachary Reid. His mother was a slave, his father the slave owner who freed her so that Zachary could be born a free man. He boards the Ibis as the ship’s carpenter, but through a series of accidents and desertions, most of the crew is lost, and by the time the Ibis reaches India, Zachary has been, out of necessity, promoted to second mate. Somewhere in this voyage, Zachary’s race has also been left behind:

Before this, the skipper had instructed Zachary to eat his meals below—“not going to spill no colour on my table, even if it’s just a pale shade of yaller.” But now, rather than dine alone, he insisted on having Zachary share the table in the cuddy, where they were waited on by a sizeable contingent of lascar ship’s-boys—a scuttling company of launders and chuckeroos.

With the introduction of the sailors called lascars, who take over for the depleted crew, Ghosh firmly establishes that the sea of poppies is also a sea of language. The original crew, including Zachary, throw around a deliciously low naval patois, a rich, wanton echo of Patrick O’Brian’s snappy sailor slang, a vernacular full of rufflers and rum-gaggers who suffer from squitters and collywobbles and dine on lobscouse, dandyfunk, and chokedog. The lascars, on the other hand, speak an entirely new language. They are a group of ten or fifteen sailors who come from places having “nothing in common, except the Indian Ocean; among them were Chinese and East Africans, Arabs and Malays, Bengalis and Goans, Tamils and Arakanese.” The culture shock for Zachary is acute:

The Captain declared them to be as lazy a bunch of niggers as he had ever seen, but to Zachary they appeared more ridiculous than anything else. Their costumes, to begin with: their feet were as naked as the day they were born, and many seemed to own no clothing other than a length of cambric to wind around their middle. Some paraded around in drawstringed knickers, while others wore sarongs that flapped around their scrawny legs like petticoats, so that at times the deck looked like the parlour of a honeyhouse.

With the new clothes comes a new vocabulary: “malum” instead of mate, “serang” for bosun, “tindal” and “seacunny” for bosun’s mate and helmsman. The deck is the “tootuck,” a command a “hookum.” When Ghosh tells us that the “cry of the middle-morning watch went from ‘all’s well’ to ‘alzbel,'” he is doing more than adding color or authenticity to his narrative. He is alerting us to the India that this novel is really about—a great cauldron of an involuntary melting pot, an uneasy cultural miscegenation. In Sea of Poppies, as in Ghosh’s vision of India, language is the tip-off, the tell-tale sign—literally, or at least audibly, telling the tale of two hundred years of imperial rule.

Advertisement

The leader of the Ibis ‘s lascars is a betel-chewing Arakan (from a region now part of Burma) named Serang Ali who speaks a crude, sly, Yankee-Chinese slang. When the captain falls ill and the inexperienced Zachary has to try to navigate, Serang Ali impatiently takes over that task:

What for Malum Zikri make big dam bobbery’n so muchee buk-buk and big-big hookuming? Malum Zikri still learn-pijjin. No sabbi ship-pijjin. No can see Serang Ali too muchi smart-bugger inside? Takee ship Por’Lwee-side three days, look-see.

This is really no less comprehensible and no more exotic than the rippling sailing vocabulary of O’Brian, but the meaning, like the origins, is utterly different. O’Brian’s slang expresses a single community of rough souls, joined together, all bent on a single task—sailing a ship. Ghosh’s suggests a collection of exiles from the four corners of the globe, men swept together by the nineteenth century’s version of globalization.

When the Ibis reaches India and an English pilot boards to steer the schooner up the Hooghly River, Zachary hears yet another vernacular:

Damn my eyes if I ever saw such a caffle of barnshooting badmashes! A chowdering of your chutes is what you budzats need. What do you think you’re doing, toying with your tatters and luffing your laurels while I stand here in the sun?

The English of the ruler has been infiltrated by the vocabulary of the ruled. A little later Zachary asks the pilot the meaning of the word “zubben,” and he is patiently told:

The zubben, dear boy, is the flash lingo of the East. It’s easy enough to jin if you put your head to it. Just a little peppering of nigger-talk mixed with a few girleys. But mind your Oordoo and Hindee doesn’t sound too good: don’t want the world to think you’ve gone native. And don’t mince your words either. Musn’t be taken for chee-chee.

If the reader is reeling in this gaudy, dancing language, Ghosh suggests, so was India. He gives us Paulette as another example, a young woman, daughter of a French botanist, raised by a Muslim wet nurse, whose speech is studded with fluent Bengali and earnest Francophone malapropisms. When her father dies and she is taken in by the rich merchant Benjamin Burnham, to be properly domesticated and taught to stop wearing saris and climbing trees, Paulette discovers that

the servants, no less than the masters, held strong views on what was appropriate for Europeans….[They] sneered when her clothing was not quite pucka, and they would often ignore her if she spoke to them in Bengali—or anything other than the kitchen-Hindusthani that was the language of command in the house.

Paulette works hard to learn how to speak the language expected of her, but the exchanges she has with Mrs. Burnham and that lady’s brilliantly wrought Victorian memsahib chatter are moments of lovely comic incomprehension:

Just the other day, in referring to the crew of a boat, she had proudly used a newly learnt English word: “cock-swain.” But instead of earning accolades, the word had provoked a disapproving frown….Mrs. Burnham explained that the word Paulette had used smacked a little too much of the “increase and multiply” and could not be used in company: “If you must buck about that kind of thing, Puggly dear, do remember the word to use nowadays is ‘roosterswain.'”

Ghosh uses the comic malaprop as an emblem of the farcical mess Britain has made in India. Baboo Nob Kissin, raised in a priestly family, educated in Sanskrit, attaches himself to his uncle’s saintly widow, Taramony, and devotes his life to making money so that they can one day build a temple. He works his way up to the position of gomusta, or agent, in charge of shipping migrant labor for the firm of Burnham Bros., while also pursuing a lucrative moneylending business on the side. When Taramony dies, Baboo Nob Kissin feels her soul lodging itself in his body, merging with him, and he begins to take on female characteristics, wearing his hair loose, his clothes flowing, adorning himself with jewelry. Even his body begins to change, becoming softer and more womanly.

When, acting as the owner’s agent, Baboo Nob Kissin meets Zachary on board the Ibis, he takes it into his head that the young sailor is an incarnation of the god Krishna. Because Burnham has decided to send the Ibis, before it begins its opium work, on a trip to Mauritius carrying a human cargo of migrant labor, Nob Kissin, wanting to stay near Zachary, suggests that Burnham send him along on the journey: “It will facilitate my work with coolies, sir, so I can provide fulsome services. It will be like plucking a new leaf for my career.”

Paulette, too, wants to join the cast of characters on the Ibis. Her life has become intolerable with the Burnhams: an odious clergyman wants to marry her and, worse, Mr. Burnham, while having her read harsh sermons out loud to him to instruct her in Christianity, has exhibited an unseemly fervor for being paddled that even the naive Paulette recognizes as something other than a purely religious taste for flagellation. She runs away, and it is Baboo Nob Kissin, in his capacity as the moneylender who once helped her father, to whom she turns for help. She explains to him that she plans to disguise herself as an Indian coolie and travel with the indentured servants:

“Miss Lambert,” said the gomusta frostily, “I daresay you are trying to pull out my legs. How you could forward such a proposal I cannot realize. At once you must scrap it off.”

Nob Kissin does eventually help Paulette get on the Ibis, but he is also, in his role as an adviser to his English employer Burnham, the brains behind a far less humanitarian act: a lawsuit that lands a young nobleman in chains, locked in the Ibis ‘s hold and on his way to a sentence of forced labor.

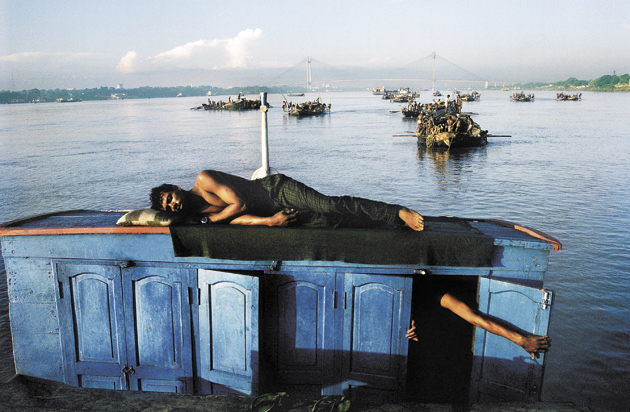

Raja Neel Rattan Halder is the zemindar of Raskhali, a young man from an old and landed family, whom we first encounter on his luxurious, stately houseboat with his young son, his mistress, and a large retinue of retainers. Neel is educated, effete, and a connoisseur, as is proper for someone of his high caste. Even kite flying has become an art in the Halder family:

The sport was much beloved of the Halder menfolk, and as with other such favoured pursuits—for example, music and the cultivation of roses—they had added nuances and subtleties that elevated the flying of kites from a mere amusement to a form of connoisseurship.

They had also accreted nuances of language:

Generations of landed leisure had allowed them to develop their own terminology for this aspect of the elements: in their vocabulary, a strong, steady breeze was “neel,” blue; a violent nor’easter was purple, and a listless puff was yellow.

Neel has recently come into the title of zemindar and has inherited the extensive Halder land holdings. But the sea of poppies laps at the feet of even this pampered young nobleman, for his father has left him heavily invested in the opium trade through the company of Benjamin Burnham. Finding himself moored in his magnificent houseboat beside the Ibis, Neel, vaguely aware of his inherited business difficulties with Burnham, invites him, Zachary, and Mr. Doughty, the pilot, to dine with him. His English is far more sophisticated than his guests’, as is his sensibility. He introduces his little son as

“My sole issue and heir. The tender fruit of my loin, as your poets might say.”

“Ah! Your little green mango!” Mr Doughty shot a wink in Zachary’s direction. “And if I may be so bold as to ask—would you describe your loin as the stem or the branch?”

Neel gave him a frosty glare. “Why, sir,” he said coldly, “it is the tree itself.”

A lively discussion of free trade takes place that night on the houseboat. Free trade is a “right conferred on Man by God,” Burnham says, explaining that the free trade of opium is particularly holy, for it allows the natives exposure to the superiority of the British; and it is the enormous profits from opium, in some years reaching almost the level of the yearly revenue of the United States, that are the only reason that Britain can sustain its rule in a country as poor as India. “And if we reflect on the benefits that British rule has conferred upon India, does it not follow that opium is this land’s greatest blessing?” Burnham asks Zachary. “Does it not follow that it is our God-given duty to confer these benefits upon others?” This self-congratulatory tautology is topped off by an entertaining consideration of the medical benefits of opium:

So you would do well to bear in mind that it would be well nigh impossible to practise modern medicine or surgery without such chemicals as morphine, codeine and narcotine—and these are but a few of the blessings derived from opium. In the absence of gripe water our children would not sleep. And what would our ladies—why, our beloved Queen herself?—do without laudanum? Why, one might even say that it is opium that has made this age of progress and industry possible: without it, the streets of London would be thronged with coughing, sleepless, incontinent multitudes. And if we consider all this, is it not apposite to ask if the Manchu tyrant has any right to deprive his helpless subjects of the advantages of progress? Do you think it pleases God to see us conspiring with that tyrant in depriving such a great number of people of this amazing gift?

Burnham, the pious and ambitious merchant from Liverpool, speaks the Queen’s English with none of the low and intrusive slang of other British characters in this novel. No “hot cock and shittleteedee!” for him. But it is no accident that the words from his mouth are in fact the most debased of all, for Burnham, the religious fanatic, sexual pervert, ruthless and vindictive businessman, and hypocrite, stands for everything Sea of Poppies condemns. He is, in one way or another, the catalyst of almost every horror that befalls Ghosh’s victims. He is, in addition, the weakest character in a literary sense, a villain as easily recognized by the modern sensibility as the mustachioed evildoer to the audience of a silent movie.

But it is often true in this novel that the historical details are more real than the characters; the language they speak more alive, more interesting and nuanced than the characters speaking it. The period, the place, its trials, and the different idioms Ghosh creates become the real beings who populate these pages, and they can have a strong presence. Burnham, on the other hand, is there to dutifully play his part in the narrative. He is not the only morally weighted character in the novel, but he is the one given the most central and didactic role.

It is Burnham who, with Nob Kissin’s advice, catches Neel in a financial trap, frames him for fraud, then strips him of his lands, his wealth, his family, his caste, and his freedom. Neel, the fastidious aesthete, winds up scraping crusted vomit off his cellmate, a Chinese opium addict withdrawing painfully from the drug. Together, they are shipped off on the Ibis. Deeti, too, ends up on the ship she envisioned in the novel’s opening passage. She has lost her daughter now, lost everything of the little she had, and is, like the other passengers, escaping one life for another. After her husband’s death, Deeti is rescued from the flames of sati by Kalua, a man of lower caste, a solitary giant who has always loved her from afar. Together, she and Kalua sell themselves into indentured servitude in order to escape Deeti’s enraged in-laws. They find themselves, with Neel, in the dark hold of the Ibis on their way to the island of Mauritius.

The Ibis is the vessel, in both senses of that word, into which the story is poured. It is the slave vessel that brings Zachary, the son of a slave, his status in a white world. It is the vessel that has come to receive a cargo of opium, the poison that scents this novel. It is the jail that finally frees Neel. It is in the hold of the Ibis that a Frenchwoman finds her true identity in an Indian disguise and that an oppressed Indian victim of rape is transformed into a woman of courage and leadership. On the deck of the Ibis, Baboo Nob Kissin feels the womanly presence of Taramony in him so forcefully that “his outer body felt increasingly like the spent wrappings of a cocoon.” The Ibis, he realizes,

was not a ship like any other; in her inward reality she was a vehicle of transformation, travelling through the mists of illusion towards the elusive, ever-receding landfall that was Truth.

And so the former blackbirder, a slave ship bringing freedom to an unlikely group of people, makes its way out to sea where there will be a mutiny, sixty lashes, a daring escape, and several secret love affairs as well. In some ways Sea of Poppies is a blustery old-fashioned pirate tale. There are actual pirates, for one thing, and the heroes and villains are exactly that: shining heroes or unmitigated villains rather than the more ambivalently observed characters of most serious modern fiction.

But Sea of Poppies is an allegory, though unlike Moby-Dick, the greatest seafaring book of all, the allegory is political and, too often, obvious. Still, Ghosh’s description of this period in India’s history as an epic adventure story is not only extremely engaging, it is at the heart of what the author is doing. Sea of Poppies is the downstairs to Kipling’s upstairs. Unlike the focused, witty, implicit criticism of the British in, for example, J.G. Farrell’s exquisitely restrained 1973 novel The Siege of Krishnapur,* Ghosh’s vision is sweeping, and if it sometimes sweeps up a heap of melodrama or thinly written characters or less-than-muscular prose along with everything else, the result is nevertheless impressive.

Farrell’s novel about an Indian uprising in 1857, which touches on some of the same subjects—including a trip to an opium factory—is a more gracefully written book, but while Farrell observes the hypocrisy and poignant farce of men and women sent to India by the British East India Company to both civilize and pillage, Ghosh climbs the great, epic mound of colorful, sorrowful detritus that these same British left in their wake. The careful, impressive prose of Ghosh’s first novel may have been left behind in this big, busy scramble of a hike, but then, to compensate us, there is the panoramic view. Sea of Poppies is unapologetically messy and broad: a celebration of the survivors of Britain’s rule, a historical catalog of obscure and fascinating detail, a joyful festival of linguistic amalgamation, and a postcolonial allegory, all set afloat in a swashbuckling tale of sea-going adventure.

This Issue

January 15, 2009

-

*

Reissued by NYRB Classics in 2004, with an introduction by Pankaj Mishra.

↩