1.

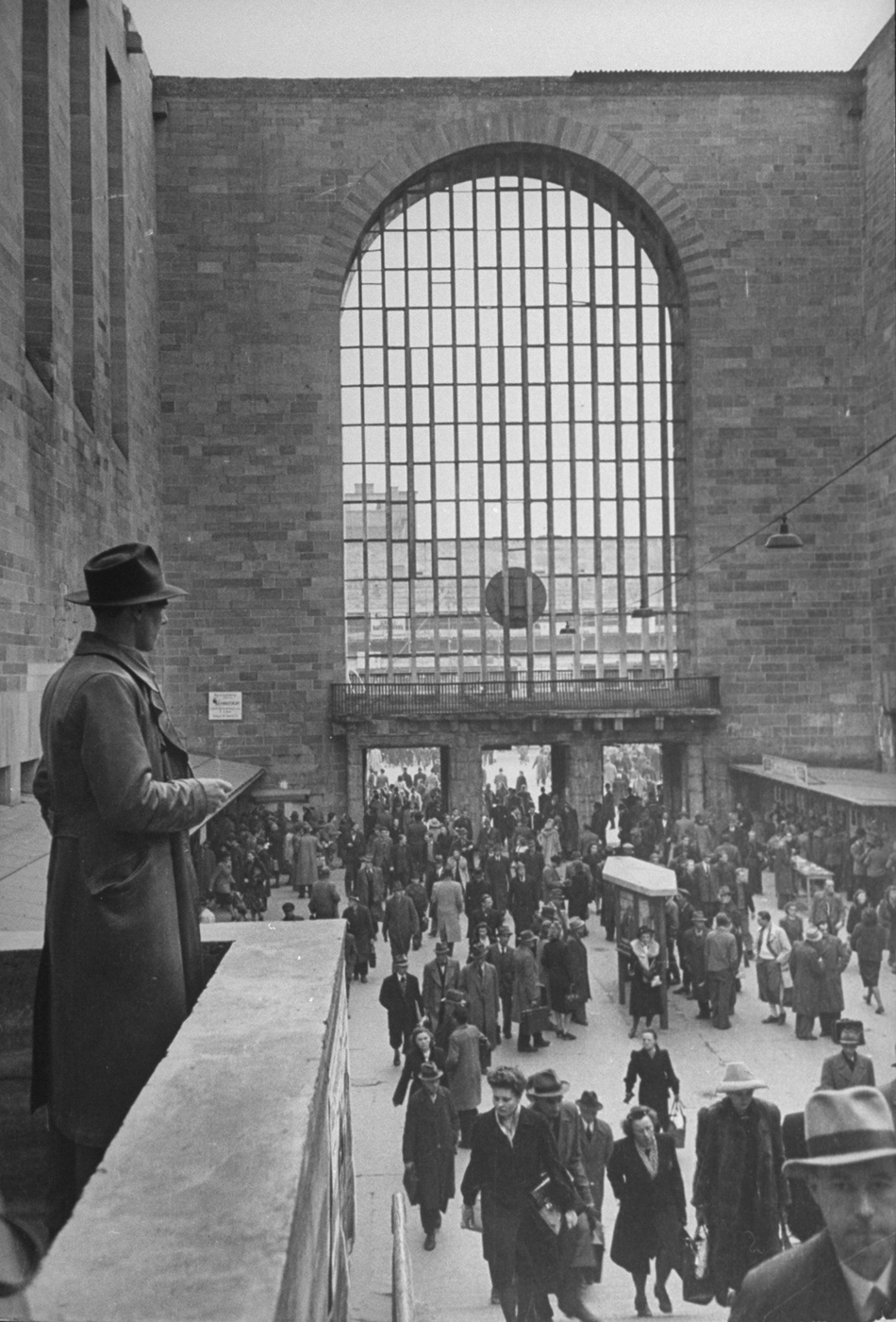

An extraordinary large-scale demonstration occurred in Stuttgart in October 2010 when 100,000 protesters—one sixth of that city’s population—took to the streets to protest the $8.75 billion transformation of Paul Bonatz and Friedrich Eugen Scholer’s Central Station of 1911–1928 into a hub of a new trans-European high-speed rail network. That controversial project, Stuttgart 21, planned by the Düsseldorf-based Ingenhoven Architects, required the demolition of the monumental terminal’s north wing in 2010 and south wing this past January, leaving the building’s 183- foot-high flat-roofed clock tower and its Romanesque-basilica-like main concourse, the latter of which will become redundant when travelers will board trains below ground.

Bonatz and Scholer’s imposing elevations of unornamented rough-hewn beige limestone established a distinctive (if somewhat conservative) local variant of Modernism that set the tone for Stuttgart’s exceptionally cohesive architecture of the 1920s and 1930s. That consistent urban vision inspired James Stirling and Michael Wilford to follow the main precepts of the so-called Stuttgart School in their sandstone-and-travertine-clad Neue Staatsgalerie of 1977–1984, the city’s most distinguished postwar urbanistic achievement and the finest example anywhere of Postmodern architecture, i.e., design that didn’t accept the Bauhaus rules against ornament or historical pastiche.

To be sure, opposition to Stuttgart 21 has not been wholly, or perhaps not even primarily, architectural, even though critical opinion reckons the station among the finest transportation facilities of the twentieth century. The new scheme also involves felling two hundred trees in the adjacent Schlossgarten, one of the city’s best-loved parks, which along with the project’s enormous cost—opponents have warned that it could exceed $23 billion—may well be the main sources of public anger. Yet even the partial destruction of Bonatz and Scholer’s masterful work (which they dubbed umbilicus sueviae, the navel of Swabia) has been rightly perceived as an irrevocable act of cultural vandalism.

How big a political issue can be made of despoiling architectural landmarks? In fact, voter disgust with both Stuttgart 21 and mainstream politicians’ evident indifference to the numerous demonstrations against it helped the Green Party to win a majority on the Stuttgart city council in 2009 and two years later to lead a coalition government in Baden-Württemberg’s legislature, a first for a German state. What has made the story of the Stuttgart Central Station especially shocking is that the historic preservation movement arose a half-century ago in direct response to the equally misguided demolition of another great railway depot: McKim, Mead & White’s majestic Pennsylvania Station of 1908–1913 in New York City.

Today we take for granted the imperative to protect architectural treasures for the edification and enjoyment of our descendants. But in 1963 an outcry from architectural historians, picket lines of outraged citizens, and a fiery New York Times editorial were not enough to save Penn Station from being plundered to make way for Charles Luckman’s irredeemably cheap-looking Madison Square Garden of 1963–1968. Yet from that senseless act of urban self-mutilation quickly arose a more protective attitude toward venerable buildings.

In 1964, the architect James Marston Fitch—whom the urbanist Jane Jacobs termed “the principal character in making the preservation of historic buildings practical and feasible and popular”—began this country’s first graduate degree program in historic preservation at the Columbia school of architecture, a giant step followed a year later by Mayor Robert F. Wagner’s creation of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission and James A. Gray’s founding of the New York–based International Fund for Monuments (known since 1984 as the World Monuments Fund). Although Fitch averred that it was not he but the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association (saviors of George Washington’s Virginia home in 1858) who launched the preservation movement in this country, there is no question of his central importance in professionalizing the discipline and suggesting economic models to make preservation an attractively remunerative proposition—what we now call adaptive reuse—rather than solely an act of altruistic beneficence.

The effectiveness of that new movement was proven a decade later when in 1975 well-organized preservationists (including Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, who became the public face of the campaign) derailed plans for a fifty-three-story Brutalist tower by Marcel Breuer to be built atop Reed & Stem and Warren & Wetmore’s Grand Central Terminal of 1911–1915 in Manhattan, a Beaux-Arts treasure second only to Penn Station. (Unfortunately there was no such movement in 1963 to stop the vast, ugly Pan Am Building by Walter Gropius and the Architects’ Collaborative from going up next to the terminal.)

Despite such conspicuous victories, undesignated landmarks are still routinely endangered and too often destroyed, provoking periodic demands for stricter safeguards. Private ownership often trumps communal benefit, and the US Supreme Court’s baneful decision in Kelo v. City of New London (2005) allows the use of eminent domain to supersede other factors including landmark ordinances.

Advertisement

Nonetheless, there are some who believe that historic preservation has gotten out of hand and thwarts innovative architecture and city planning. That was the premise of “Cronacaos,” a quintessentially contrarian exhibition organized by Rem Koolhaas that was first seen at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2010 and then traveled the following spring to New York’s New Museum. In this visually deficient show, Koolhaas asserted that some 12 percent of the earth’s surface is now barred from new construction because of various restrictive regulations—historic preservation, land conservation, and the like—and thus the full creative potential of the building art is stiflingly inhibited by what he sees as an excessive, sentimental attachment to older architecture.

That proposition sounded rather ironic coming from the author of the stupendous Central China Television Headquarters of 2004–2012 in Beijing, in the veritable shadow of which has unfolded one of the most deplorable preservation disasters in recent memory: the systematic devastation of the city’s historic hutong, or alleyway quarters.* Among the recent victims of this replay of the barbaric sacking of artistic treasures during Mao’s Cultural Revolution was the siheyuan, or courtyard house, of the revered architects, historians, and preservationists Liang Sicheng (1901–1972) and his wife, Lin Huiyin (1904–1955). In order to escape notice, the authorities suddenly razed it last January during Lunar New Year festivities; yet the demolition set off an international uproar.

In a 2007 article in The Guardian, the architecture critic Jonathan Glancey called the CCTV building “the most dramatic of these hutong-gobblers,” but noted how Koolhaas showed him snapshots of the endangered landmarks and wistfully commented that “people, I think, miss their old life down below in the courtyards.” Glancey cited this contradiction as “exactly the kind of paradox [Koolhaas] revels in. In public, he is the master of sock-it-to-me design; in private, he looks with affection at…an old way of oriental life likely to vanish.”

2.

For all their good intentions, many nominal supporters of landmarks preservation have little actual idea of the complex political, economic, aesthetic, technical, and interpretive issues that affect historic structures. In his admirable and much-needed general introduction to the subject, Time Honored: A Global View of Architectural Conservation, John H. Stubbs (who studied under Fitch at Columbia, worked with him at the New York architecture-and-preservation firm Beyer Blinder Belle, guided field operations for the World Monuments Fund for two decades, and now directs the masters preservation program at Tulane) sets forth a smoothly organized, well-paced survey of landmarks preservation through the ages and highlights several turning points in changing attitudes toward historic architecture since ancient times. Stubbs is eloquent about what he presents as historic preservation’s potential for easing the traumas of globalization:

Our ever-expanding knowledge of other people and places, both in the present and across time, offers improved abilities to interpret and present heritage sites as well as increased opportunities for international exchange and cooperation. The marvels of humanity’s past—and the issues we face in understanding and conserving them—are topics of concern as never before.

Time Honored also offers a concise (and cautionary) summary of preservation methods in the premodern period, extensive bibliographic references, and useful listings of preservation groups. Equal parts primer, chronicle, textbook, and source guide, it should become the basic publication for laymen and an indispensable reference for specialists. Among the sites it discusses in depth are Rome’s historic center, ancient Pompeii, Angkor in Cambodia, Beijing’s Forbidden City, Old Havana, the Marais quarter in Paris, and New York City. The absence heretofore of a comparably thoroughgoing but accessible resource on a topic of such urgent public concern was a glaring lapse that makes this deeply researched, lucidly written, and helpfully annotated book an invaluable addition to the literature.

Stubbs and Emily G. Makaš’s equally excellent companion volume, Architectural Conservation in Europe and the Americas, is a country-by-country compendium of case histories that, taken as a whole, display what must approach a complete range of the concerns at play in historic preservation today. From such well-known and long-vexed sites as the Athenian Acropolis to more contemporary locales like the Space Age Modernist capital city of Brasília, the conflicting and not always neatly resolvable forces that bear upon preservation are addressed as clearly and thoughtfully as the general reader could hope for.

The unprecedented challenges presented to architectural conservationists by the aging landmarks of Modernism—the specific writ of the preservation group Docomomo International, organized in Holland in 1988—are well described in Jeffrey M. Chusid’s Saving Wright: The Freeman House and the Preservation of Meaning, Materials, and Modernity, a detailed record of his decisive work in stabilizing and restoring Frank Lloyd Wright’s Freeman House of 1923–1925 in Los Angeles. This exotic aerie perched on a steep plot in the Hollywood Hills was one of Wright’s four LA-area essays in “textile block” construction, a building method he devised wherein hollow precast concrete blocks were joined together by an intricate internal network of steel tie-rods.

Advertisement

Chusid, an architect who teaches preservation at Cornell, was director and restoration architect of the Freeman House for eleven years starting in 1986, when the crumbling structure was given to the University of Southern California after Harriet Freeman died at ninety-six—having lived in the house for more than six decades. Chusid’s exhaustive account of the complexities of preserving this important work from the greatest American architect’s least productive period also provides a social history of the freethinking, high-bohemian Southern California patrons who embraced Wright after his career imploded following the scandal ignited by his elopement with a client’s wife, which culminated with her murder by an insane servant in 1914.

Wright’s two major projects of the ensuing twenty-year midlife dry spell—his Imperial Hotel of 1916–1923 in Tokyo and Hollyhock House of 1916–1921 in Los Angeles (a sprawling residence and private performing arts center for the Standard Oil heiress Aline Barnsdall)—required several trans-Pacific journeys, and those far-flung jobs redirected his creative vision away from the waning Arts and Crafts ethos of his midwestern Prairie House phase during the century’s first decade. When he relocated to LA in 1921 he rejected California’s Spanish Colonial style just as he had earlier forsworn other historical revivalism and sought a novel but regionally appropriate alternative.

Wright turned to the architecture of ancient Mesoamerica as a suitable, ecologically proven prototype. He adapted the solid masonry massing, flat rooflines, and stylized ornament confined within small sculptural squares reminiscent of pre-Columbian architecture for his new approach to California living. Wright was always intrigued by innovative technologies and standardized designs whereby his revolutionary ideas could reach a far broader audience than the well-to-do arts enthusiasts who commissioned his custom-built houses. Between 1912 and 1916 he had developed a series of small, prefabricated domestic schemes, the American System-Built Homes, but they never caught on, and he hoped to have better luck with his textile block system.

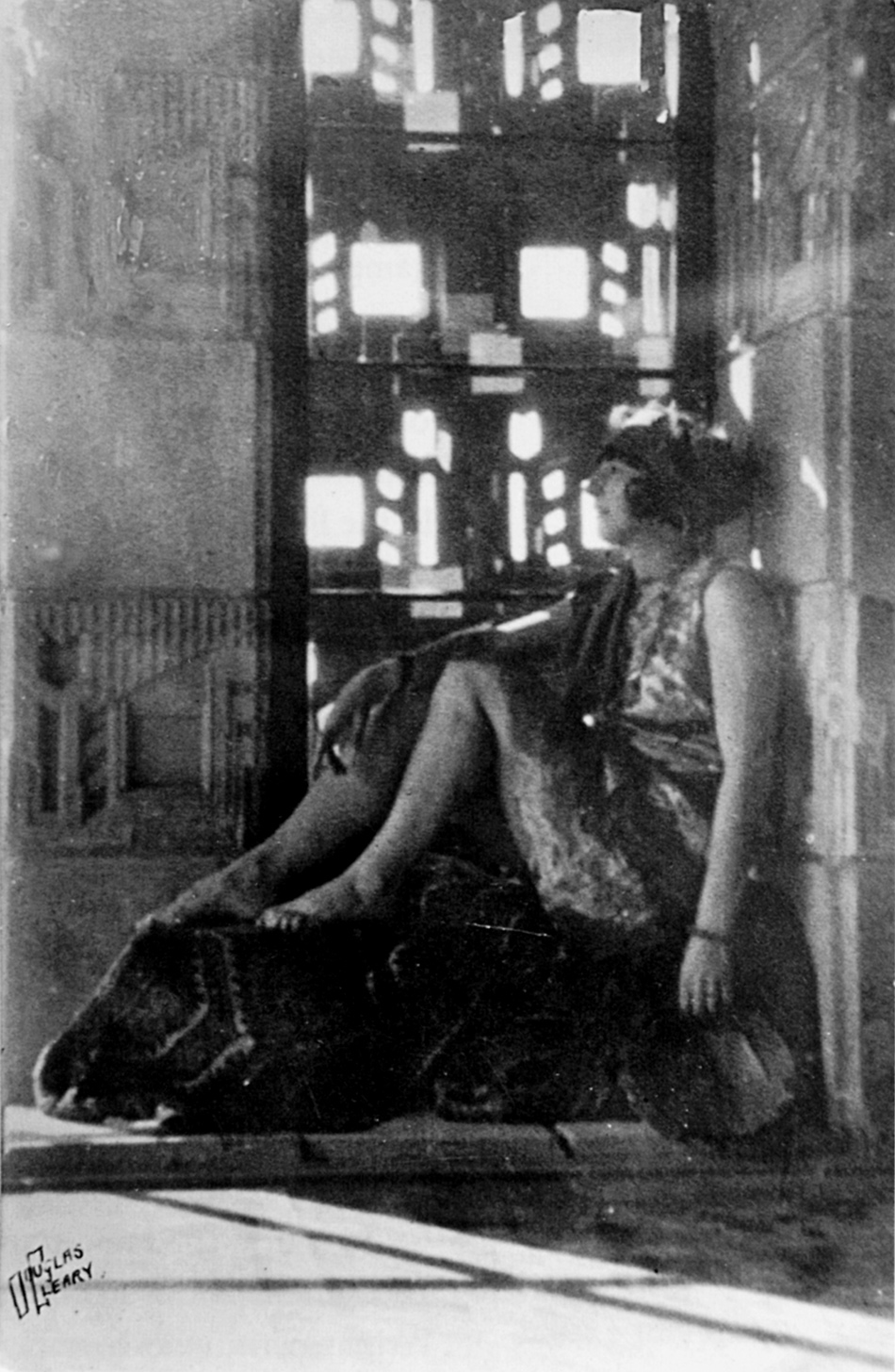

In typically Wrightian fashion, his LA houses were much more enclosed than the later indoor-outdoor compositions of his former assistant Richard Neutra, a Viennese émigré who preceded him to the West Coast and there used large expanses of glass in ways his old boss never ventured. Far from the sun-washed interiors characteristic of Neutra’s approach, the dim rooms of Wright’s 1920s LA houses were gently dappled with discrete motes of daylight filtered through small apertures in his concrete building blocks. He needed seventy-four different molds to give a range of geometrically embossed and pierced blocks varied enough to create the rich tapestry-like patterns of interior light he desired.

Wright’s biggest mistake in erecting the Freeman House was to skimp on materials and labor. Instead of taking pains to have each hand-cast block carefully crafted, the task was left to unskilled workers. As Wright ruefully but frankly wrote in 1927:

We had no organization. Prepared the molds experimentally. Picked up “Moyana” [mañana?] men in the Los Angeles street…. The work consequently was roughly done and wasteful.

Thus the internal fabric of the house was a mess from the first. Things were not helped when Wright left LA for good in 1924 and fobbed off supervision of the complicated job onto his overwhelmed architect son, Lloyd, whom he directed via telegram. Chusid’s account of the building and breakdown of the house is both meticulous and troubling.

Experimental architecture by its very nature is more prone to the depredations of time and natural elements than buildings made from conventional materials through traditional methods. Avant-garde architects often simply do not know how the products of their imagination will perform when implemented, especially if untested components are involved. According to a recent report on NPR, the titanium-zinc-alloy cladding of Koolhaas’s CCTV building is already showing damaging effects of Beijing’s poisonous air pollution only four years after the material was installed and even before the megastructure is fully occupied. One feels fairly certain, however, that its architect will be in favor of the preservation of this latter-day landmark.

3.

High among the unpredictable variables that endanger the survival of worthy buildings are the vagaries of taste. For example, by the late 1950s, Victorian architecture was held in such low esteem that Frank Furness’s splendidly oddball University of Pennsylvania Library of 1889–1891 in Philadelphia—akin to a Venetian-Gothic armadillo—faced impending demolition. Although several commercial buildings by Furness fell to the wrecker’s ball around that time in order to satisfy narrow-minded city planners’ Georgian-only vision of the newly created Independence National Historical Park nearby in downtown Philadelphia, a parallel catastrophe on the Penn campus was averted thanks to the special pleading of Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi, among others including Wright, who after a 1957 walk-through of the Furness library proclaimed, “It is the work of an artist.”

The following year saw the founding in London of the Victorian Society, the pioneering group dedicated to preserving that long-derided style, and in 1966 a sister organization, the Victorian Society in America, followed suit even as urban homesteaders from Brooklyn to San Francisco were rediscovering the quirky charms of the diverse range of fanciful design subsumed under the portmanteau term “Victorian.” By the 1980s there was widespread disbelief among a younger generation that there could ever have been such utter contempt for this delightfully imaginative mode.

One wonders, though, if a similar volte-face will ever happen with Brutalist architecture, the postwar style identifiable by assertive, not to say aggressive, geometric forms in unfinished concrete (béton brut in French, hence the name). Among America’s most critically acclaimed public works of the Sixties was Kallmann McKinnell & Knowles’s Boston City Hall of 1962–1968, a top-heavy, fortress-like Brutalist structure erected next to historic Faneuil Hall and influenced by Le Corbusier’s Couvent de Sainte-Marie de La Tourette of 1953–1960, a Dominican monastery in the countryside near Lyon. Though the Boston building won praise for its bold attempt to recast civic grandeur in new architectural forms, few questioned if an inward-turning rural religious cloister was the optimal model for the governmental offices of a twentieth-century American city.

With the opening in 1976 of Benjamin C. Thompson’s hugely popular Faneuil Hall Marketplace—the first and most successful of the inner-city food-and-shopping malls promoted as “festival marketplaces” by their populist-minded developer, James Rouse—the adjacent Boston City Hall soon began to look more menacing than monumental, more defensive than defensible. In 2006 the city’s mayor asked for the démodé pile to be sold and the seat of municipal government moved to South Boston. In a Catch-22 all too typical of toothless preservation regulations, the Boston Landmarks Commission declined to declare the building a landmark unless it was in imminent danger of destruction. The financial crash of 2008 forced the relocation plan to be shelved, and the fate of this once-admired, nowdisparaged architectural survivor remains uncertain.

Surely no American Brutalist’s works have had a tougher time lately than those of Paul Rudolph, whose reversal of critical fortune long predated his death in 1997. Beginning in the early 1950s, his intriguingly sculptural, spatially dynamic concrete structures beguiled critics and design buffs alike, particularly his Art and Architecture Building of 1959–1963 at Yale, where Rudolph served as dean from 1958 to 1965. The building has thirty-seven separate levels breaking up space of what would conventionally be seven floors. He was succeeded in that post by the Postmodernist Charles Moore, who viscerally disliked what he viewed as his predecessor’s overbearing, inhumane designs and encouraged students to freely alter the new Yale school’s interiors in accord with his own very different, “inclusive” attitudes.

When the A&A Building was gutted by a fire of suspicious and unproven origin in 1969, Moore appeared to be insufficiently perturbed, and Rudolph hated him until the day he died. A scrupulous $126 million renovation by Gwathmey Siegel Architects finally brought the A&A Building back to its original condition in 2006, but alas that exemplary effort was fatally undermined by the firm’s dreadful addition, a graceless composition that neither defers sufficiently to nor contrasts effectively enough with Rudolph’s original, and seems wrong in just about every way possible. Still less fortunate was Rudolph’s Riverview High School of 1957–1958 in Sarasota, Florida, his first large-scale public project, which was torn down in 2009. Several of his early houses have likewise been destroyed in recent years, structures built predominantly of wood, and remarkable for their lightness and airiness, in complete contrast to his ponderous public commissions.

Given such attrition, fans of Rudolph’s work (mainly coprofessionals able to see past the many impractical and unlivable aspects of his designs) were dismayed to learn that yet another building from his brief heyday was also in danger of disappearing: his Orange County Government Center of 1963–1967 in Goshen, New York—a busy, boxy composition of rectangular forms pulled away from a wall-like backdrop that resembles a low, wide filing cabinet with its drawers half-opened at random. It has been plagued from the outset by functional problems, including leaks attributable to the relatively small building’s eighty-seven separate roofs.

How much taxpayers might be willing to spend to save a building many deem an eyesore was again rendered moot by the weak economy. In May, the Orange County Government Center won a de facto stay of execution when the county legislature rejected a $14.6 million bond issue to fund a replacement for the damaged structure, another example of benign architectural neglect imposed by the recession. The question remains, however, of what will happen to such unloved relics when better times return. Beauty may be in the eye of the beholder, but ugliness seems easier for many nonspecialists to define. As one architecturally trained Orange County resident told The New York Times:

There are plenty of people who say [the government center] is ugly. The only response that I have to that is this: Define ugly. A lot of people don’t like Picasso. Does it mean a Picasso doesn’t deserve as much attention and respect as a Monet? Does it mean we get rid of the Guggenheim because it looks like a toilet bowl?

Rudolph’s Orange County Government Center is hardly comparable to one of Wright’s most thrilling works, but it is not a stretch to include the Guggenheim among the forerunners of Brutalism (although its architect had the museum’s colossal concrete coils painted, contrary to standard Brutalist practice). Masters on the order of Wright or his Victorian antecedent Furness are rare enough. Yet in a world of ever-diminishing resources, it seems unconscionably profligate not to allow future generations to decide for themselves which architectural works of the past they wish to enrich their own times. The choice should be theirs, not ours.

-

*

See my piece “The Master of Bigness,” The New York Review, May 10, 2012. ↩