Charles Simic is one of our most celebrated living poets. He has won a Pulitzer, a MacArthur Fellowship, the Wallace Stevens award, the Frost Medal, the Zbigniew Herbert International Literary Award, and served as the US poet laureate. What’s striking is that his distinctive poetic style continues to feel modest, seemingly casual, with a built-in shrug of bemused puzzlement before life’s anomalies. Most of the time it’s a good-humored shrug, though there are moments when ferocity breaks in, along with an Eastern European recognition of historical tragedy, as befits “someone like me who had the unenviable luck of being bombed by both the Nazis and the Allies.”

With the passing of Mark Strand, Galway Kinnell, Kenneth Koch, and Maxine Kumin, Charles Simic is one of the last remaining members of that marvelous generation of writers born before 1940 who did so much to reinvigorate American poetry. The Lunatic, his newest poetry collection, is his thirty-sixth. Simultaneously, Ecco, his publisher, has brought out The Life of Images: Selected Prose, which contains the cream of his six previous prose collections, and confirms that he is not only one of our finest poets, but a singularly engaging, eminently sane American essayist.

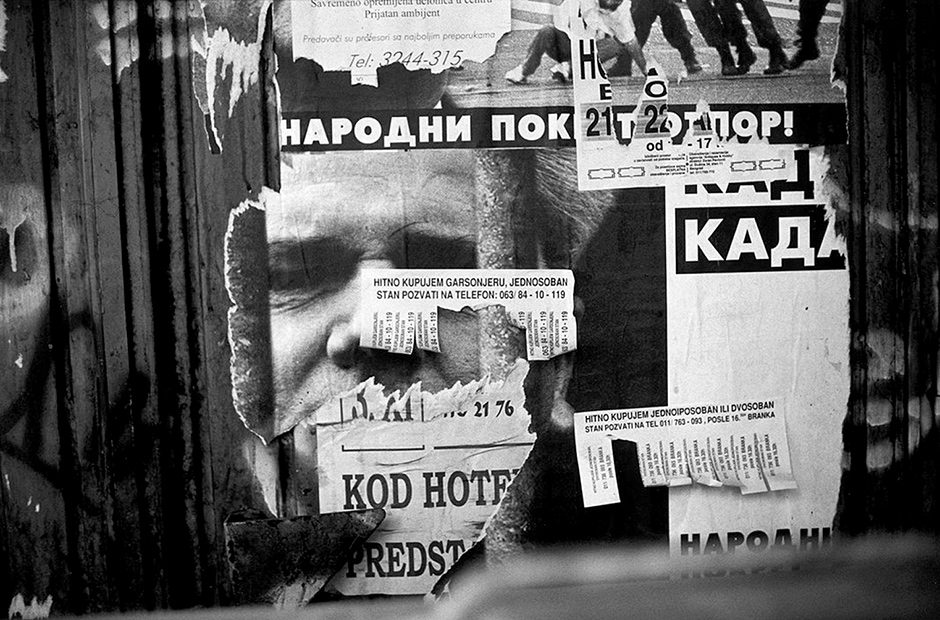

It’s through his nonfiction that we learn the basic facts about Simic’s life. Born in 1938, he grew up in Belgrade during the war. “I’m also a child of History. I’ve seen tanks, piles of corpses, and people strung from lampposts with my own eyes.” Still, he regarded his childhood as happy, being too young to imagine an alternative. It was when the war ended that things got really tough: food was scarce, and people sold whatever they could for edibles. In the course of the war and its aftermath, his father was separated from the family, and his mother tried to sneak Charles and his brother into Austria to rejoin him. When stopped by a British colonel who demanded to see their passports, “my mother replied that had we had passports, we would have taken a sleeping car.” They were sent back to Belgrade, and only when Charles turned sixteen, in 1954, were they able to emigrate to the United States, settling in Chicago.

Simic portrays his father, from whom he had been separated for ten years, with tender affection as his model: a tolerant, easygoing man who loved good food, music, pretty women, and philosophy, who had no use for organized religion but liked to visit houses of worship. (He is less kind to his mother, who comes across as something of a diva and a hypochondriac.) When his parents broke up Simic left home, taking night classes at the University of Chicago while working days at the Chicago Sun-Times.

He was initially drawn to Surrealism and the collages of Max Ernst. A lifelong insomniac, he read philosophy at night, searching for the larger, hidden meanings of existence. He was fond of Wittgenstein’s statement “It is not ‘how’ things are in the world that is mystical, but that it exists.”

One winter day in the Chicago El, he was hit like a bolt with the incredible fact that the world existed, and he in it. Moving to New York City, where he lived in a fleabag hotel, he finished college, staying up nights listening to the blues and reading philosophy, which now began to merge with a newfound interest in poetry:

The pleasures of philosophy are the pleasures of reduction—the epiphanies of hinting in a few words at complex matters. Both poetry and philosophy, for instance, are concerned with Being. What is a lyric poem, one might say, but the recreation of the experience of Being. In both cases, the need to get it down to its essentials, to say the unsayable and let the truth of Being shine through.

Here we come to one of the paradoxes in these essays: on the one hand, a dedication to the intellect at its most articulate, to reading all the books in the library, as he says “children of immigants,” insecure and playing catch-up, are wont to do; and on the other, an insistence on all that remains “unsayable”—on the failure of language to do justice to “moments of heightened consciousness.” Arguing with a friend who insisted that “‘what cannot be said, cannot be thought’…I blurted out something about silence being the language of consciousness….” It is characteristic of Simic to portray himself as a clumsy thinker rather than a trained intellectual, blurting out this hasty koan. He quotes approvingly Gilbert Sorrentino’s dictum that “at the moment the writer realizes he has no ideas he has become an artist.”

What, then, should replace thinking and ideas? A cultivation of awe. Admitting that he does not believe in God, Simic nevertheless recognizes a spiritual pull to find hidden meaning in the physical world. “Awe is my religion, and mystery is its church,” he declares. In his poetry, this sometimes leads to an overuse of perplexity bordering on the faux-naif. One of the ways he invites the mysterious is by opening himself to chance, that favorite tactic of the Surrealists. “Others pray to God; I pray to chance to show me the way out of this prison I call myself.”

Advertisement

Again playing the amateur, he says that in writing poetry

one has, for the most part, no idea of what one is doing. Words make love on the page like flies in the summer heat and the poet is merely the bemused spectator. The poem is as much the result of chance as of intention. Probably more so.

It is a commonplace for poets to say, “The poem is smarter than I am. Now I go where it wants to go.” That may be true; but at the same time, Simic is too lucid and accessible, too much the poetic craftsman, to let chance take over completely. “My entire practice…consists of submitting to chance only to cheat on it.” He recognizes that his conscious mind is at the helm: “The reputation of the unconscious as the endless source of poetry is over-rated.”

Further complicating his aesthetic, Simic says that “all genuine poetry in my view is antipoetry.” While he disdains to elaborate on that aphorism, elsewhere he quotes Nicanor Parra, the wonderful Chilean author of Poems and Antipoems. We might also recall Wallace Stevens’s comment in his preface to the Collected Poems by William Carlos Williams: “The anti-poetic is that truth, that reality to which all of us are forever fleeing.” For Simic, the anti-poetic also meant submitting to the advice of the Chicago working-class intellectuals he met:

I was all ready to put on English tweeds with leather elbow patches and smoke a pipe, but they wouldn’t let me: “Remember where you came from, kid,” they reminded me again and again.

There’s no question they had me figured out. Thanks to them, I failed in my natural impulse to become a phony.

Simic’s poetic method has remained fairly consistent over the last forty years. He has written: “My effort to understand is a perpetual circling around a few obsessive images.” His language is rather simple and conversational rather than densely textured, and it carries a faint European accent. One might be tempted to surmise that, as an immigrant for whom English is a second language, he was making do with a bare, spare diction—though switching to English had the opposite effect on Conrad and Nabokov, driving them toward verbal baroque. Moreover, Simic’s prose displays a larger lexicon and more varied syntax, so we must conclude that the choice of a stripped-down manner in poetry is highly intentional. If “words are impoverishments” to begin with, as he asserts, why show off a big vocabulary? The common speech approach also indicates a certain allegiance to the William Carlos Williams pole of modern American poetry.

Simic’s poems are noted for their wry, forlorn tone of wonder at the everyday, and their delightful flashes of humor, as well as the occasional bizarre turn: the amiable quotidian may suddenly darken, bearing witness to some cruelty or violence. While not strictly metrical, they exhibit a remarkable ear for the rhythmic beats of a line, so that even when the language verges on the prosy, we never lose awareness that we are reading a poem. His stanzas are constructed tightly, with lines around the same length and a flow unobtrusively mingling end stops and enjambments.

Though Simic has compared Emily Dickinson’s poems to Chinese boxes, his interest in Joseph Cornell would seem to point to that rectangular inspiration. Cornell (however much he might have resisted the Surrealist label) brought together uncanny combinations in close proximity. Simic compares a Cornell box to

a place where the inner and the outer realities meet on a small stage…. The boxes actually make me think of poems at their most hermetic. To engage imaginatively with one of them is like contemplating the maze of metaphors on some Symbolist poet’s chessboard. The ideal box is like an unsolvable chess problem in which only a few figures remain after a long intricate game whose solution now seems both within the next move or two and forever beyond reach.

Simic’s own tantalizing poetic compositions, usually running between eight and sixteen thin-columned lines, with a handful of images left on board, are tightly mitered boxes that seem both transparent in their meaning yet impossible to prise open completely.

In his latest collection, The Lunatic, its title aside, there is less of the mad or grotesque, and more of a quiet waiting for the end. The customary situation finds the poet lying in bed, unable to sleep, “the uncrowned king of the insomniacs.” His night thoughts flitter about, taking him past a set of imagined scenes, often ending in the graveyard. He begins one poem, “Scribbled in the Dark”:

Advertisement

Sat up

Like a firecracker

In bed,Startled

By the thought

Of my death.

There is nothing particularly morbid about these nocturnes, simply the recognition of what may likely befall an elderly author. Another poem ends:

I hear a pack of cards being shuffled,

But when I look back startled,

There’s only a moth on a window screen,

Its mind like mine too wired to sleep.

He and the moth are locked together in insomniac jitters: the very threadbareness of the incident provides the comedy. Other poems seem to spring from the lassitude of summer afternoons’ interrupted naps. Desire rarely intrudes on the present, but it does visit, as with Cavafy, in the form of retrieved memories:

STORIES

Because all things write their own stories

No matter how humble

The world is a great big book

Open to a different page,

Depending on the hour of the day,Where you may read, if you so desire,

The story of a ray of sunlight

In the silence of the afternoon,

How it found a long-lost button

Under some chair in the corner,A teeny black one that belonged

On the back of her black dress

She once asked you to button,

While you kept kissing her neck

And groped for her breasts.

A fairly contained set of words recurs in these seventy poems: light, leaf, thought, trees, night, fleas, bird, mirror, cards, graveyard, snow, pigeons, breasts, fireworks, old man, old woman. Simic shuffles these terms as though following some Surrealist game of chance, with the result that the book has a taut, inward-revolving unity. It may seem as though he’s writing the same poem over and over, but then a sudden twist will take it to a startling place:

SO EARLY IN THE MORNING

It pains me to see an old woman fret over

A few small coins outside a grocery store—

How swiftly I forget her as my own grief

Finds me again—a friend at death’s door

And the memory of the night we spent together.I had so much love in my heart afterward,

I could have run into the street naked

Confident anyone I met would understand

My madness and my need to tell them

About life being both cruel and beautiful,But I did not—despite the overwhelming evidence:

A crow bent over a dead squirrel in the road,

The lilac bushes flowering in some yard,

And the sight of a dog free from his chain

Searching through a neighbor’s trash can.

In the aftermath of erotic bliss, there is always some dog going through the garbage can to remind us of the self-absorbed indifference of our fellow creatures.

The absence of razzle-dazzle in these poems is salutary. Can we consider this the by-product of a late manner? The late manner of some modern poets (such as Boris Pasternak and Eugenio Montale) moves toward direct statement, as though they no longer felt the need to demonstrate their poetic bona fides with metaphorical inventiveness. Simic has never left off summoning images, but now they seem to pass before his insomniac eyes without having to feed a larger point. Poems may start in the middle of a monologue (“And then there is our Main Street/That looks like/An abandoned movie set/Whose director/Ran out of money and ideas”) or end abruptly, like one about a goldfish tossed in a rain puddle, in a throwaway line: “Yeah, poor fish.”

In his essays, many of which first appeared in these pages, we hear another voice, that of the cosmopolitan intellectual, university professor, and raisonneur. The range is impressive, covering visual art, blues, jazz, food, politics, cities, and all types of literature. Very occasionally, a negative judgment will appear, but for the most part these are appreciations. Especially strong are his sympathetic biographical essays on certain writers who led tragic lives or took extreme aesthetic positions, such as Marina Tsvetaeva, E.M. Cioran, and Witold Gombrowicz, all of whom went further into lonely eccentricity than he was inclined to go.

If he is intrigued by Gombrowicz’s provocative defense of immaturity, he finally comes down on the side of the more equable Czesław Miłosz. His characterization of the Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai (“how levelheaded he stayed to the very end, balancing his philosophical gloom against a lust for life”) could apply to Simic himself. Quoting Brendan Gill’s “the first rule of life is to have a good time,” he displays his own knack for enjoyment by writing with zest about eating sausages and chili, listening to jazz, and walking through a big city’s streets. Wondering whether we can even have modern literature without a city, he rhapsodizes: “If New York is not already heaven, then I don’t know what is.” He can take a pass on Nature. “I could never free myself from the thought that Nature is that which is slowly killing me.” Meanwhile, he lives half the year in New Hampshire: “With five months of snow and foul weather, one has the choice of dying of boredom, watching television, or becoming a writer.”

Some of Simic’s most powerful, expressive prose can be found in three essays that deal with the breakup of Yugoslavia. His opposition to any utopian project, including nationalism, which would place a collective interest above the safety of the individual, is unremitting. As Slobodan Milošević was taking power in Serbia, Simic warned early on that he was “bad news,” and for his pains was denounced by Serbian nationalists as a traitor. His answer: “The lyric poet is almost by definition a traitor to his own people.” As he saw it, “sooner or later our tribe always comes to ask us to agree to murder,” which is one good reason he has resisted tribal identification with a passion: “I have more in common with some Patagonian or Chinese lover of Ellington or Emily Dickinson than I have with many of my own people.” Leery of all generalizations, he insists again and again that “only the individual is real.” As the civil war heated up, he found that his appeals to forgiveness and reasonableness were met with total incomprehension and finally hatred. Simic, living in America, became the target of rumors:

My favorite one was that the CIA had paid me huge amounts of money to write poems against Serbia, so that I now live a life of leisure in a mansion in New Hampshire attended by numerous black servants.

If he is still able to extract wry humor from the situation, elsewhere he rises to a furious eloquence. There is no longer any hint of mystery or the “unsayable” in these political essays; he knows exactly what he wants to say:

All that became obvious to me watching the dismemberment of Yugoslavia, the way opportunists of every stripe over there instantly fell behind some vile nationalist program. Yugoslav identity was enthusiastically canceled overnight by local nationalists and Western democracies in tandem. Religion and ethnicity were to be the main qualifications for citizenship, and that was just dandy. Those who still persisted in thinking of themselves as Yugoslavs were now regarded as chumps and hopeless utopians, not even interesting enough to be pitied.

In the West many jumped at the opportunity to join in the fun and become ethnic experts. We read countless articles about the rational, democratic, and civilized Croats and Slovenes, the secular Moslems, who, thank God, are not like their fanatic brethren elsewhere, and the primitive, barbaric, and Byzantine Serbs and Montenegrins….

Anyone who, like me, regularly reads the press of the warring sides in former Yugoslavia has a very different view. The supreme folly of every nationalism is that it believes itself unique, while in truth it’s nothing more than a bad xerox copy of every other nationalism. Unknown to them, their self-delusions and paranoias are identical. The chief characteristic of a true nationalist is that special kind of blindness. In both Serbia and Croatia, and even in Slovenia, intellectuals are ready to parrot the foulest neofascist imbecilities, believing that they’re uttering the loftiest homegrown sentiments. Hypocrites who have never uttered a word of regret for the evil committed by their side shed copious tears for real and imaginary injustices done to their people over the centuries. What is astonishing to me is how many in the West find that practice of selective morality and machismo attractive.

With finely controlled sarcasm, Simic demonstrates the advantages of an émigré’s double vision. It enables him to see how his uncle Boris “had a quality of mind that I have often found in Serbian men. He could be intellectually brilliant one moment and unbelievably stupid the next.” If Simic is finally harder on the Serbs, despite acknowledging that there were war criminals in every faction, he explains: “Nonetheless, it is with the murderers in one’s own family that one has the moral obligation to deal first.”

Simic has summarized his experience-derived, harshly un-American-sounding outlook as follows: “Innocents suffer and justice is rare is the story of history in a nutshell.” Knowing that, he continues to seek to find

a larger setting for one’s personal experience. Without some sort of common belief, theology, mythology—or what have you—how is one supposed to figure out what it all means? The only option remaining, or so it seems, is for each one of us to start from scratch and construct our own cosmology as we lie in bed at night.

At age seventy-seven he is still starting from scratch, and writing in bed, his favorite writing spot, alone with the moth, there being, as he sees it, no other option.