If public housing is the physical manifestation of a hope for social progress, that hope has its own historical twist in the United States. After the abolition of slavery in 1865, white Americans, faced with the prospect of living with African-Americans, opted for segregation. In the southern United States segregation was not only de facto but also de jure. Jim Crow laws, passed by local governments as early as the 1870s and 1880s, mandated the segregation of public facilities, education, and transportation.

When it came to housing, segregation was enforced through racially restrictive covenants—binding legal obligations written into the deed of a property by the seller that barred African-Americans (and other minorities) from buying, leasing, or using it. The practice was common in both the southern and northern United States. Ironically, it was the National Housing Act of 1934—part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal—that established housing segregation throughout the country. The newly created Federal Housing Administration’s Underwriting Manual expressly identifies “an incompatible racial element” within neighborhoods as a liability and recommends that the social and racial structure of neighborhoods be maintained by restrictions on eligibility for mortgages. It wasn’t until the Fair Housing Act of 1968 that such practices were abandoned and housing segregation was definitively banned.*

De facto racial segregation in American cities has continued, however, especially in public housing. Nine of the ten most racially segregated American cities are all located in the North, the “Land of Hope” during the Great Migration of African-Americans from the South between 1915 and 1970. In 2010, the list was topped by Chicago, where a history of racially restrictive covenants had pushed African-Americans almost entirely to what became known as the “Black Belt,” on the city’s South Side. This segregation was reinforced by the public housing program implemented by the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA), established in 1937. Before World War II, the agency built four projects, of which one was for blacks: the Ida B. Wells Homes, located in Bronzeville, the social center of the Black Belt. Consisting of 1,662 units in a mix of row houses and apartment buildings occupying several city blocks, the Ida B. Wells Homes were the largest public housing project in Chicago at the time, incorporating the existing Madden Park, where the inhabitants of the crowded Black Belt had been enjoying a variety of sports, open-air movies, and musical programs.

The way nature helped African-Americans endure the segregated spaces they inhabited in and around Chicago forms the subject of Brian McCammack’s Landscapes of Hope. The book covers the period between 1915 and 1940, the first phase of the Great Migration, which for African-Americans in the North marked “the transition away from rural agricultural economies and toward modern industrial economies.” If in the South nature was associated with labor, for the inhabitants of the crowded tenements in Chicago, nature increasingly became a source of leisure in city parks, beaches, and rural areas nearby—in resorts, forest preserves, and youth camps. On the one hand it reminded African-Americans of their homes in the South—despite the hardships they endured there, the landscapes and climate they left behind were missed by many—while on the other hand it provided “a complement to modern urban conditions,” McCammack concludes.

Perhaps the most representative “landscape of hope” in McCammack’s book is Chicago’s Washington Park. Designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux and covering one square mile, the park was completed in 1881 in a neighborhood of German and Irish immigrants working in the stockyards and the railroads. In the late 1910s the upsurge in the construction of cheap apartments north of the park attracted many African-Americans, and by the 1920s they became its primary users, with Sunday picnics, boating, baseball, and tennis in summertime, and skating on the frozen lagoon in the winter.

However, their increasing presence in Washington Park was met with hostility and often violence by whites, as McCammack explains:

It was most often African Americans, not whites, who stood to be beaten or raped by gangs of young white men…; even couples simply sitting on park benches together were targeted, victims of racist whites who resented the park’s racial transition in the Great Migration era.

He also cites The Chicago Defender—the most important newspaper advocating African-American rights at the time—which reported on attacks carried out by “young hoodlums.” Public space—this time the beach at Lake Michigan—was also the scene of violence in 1919. The killing of a seventeen-year-old boy for trespassing the imaginary line that divided blacks and whites at the beach sparked a race riot that lasted five days and resulted in thirty-eight deaths (twenty-three blacks and fifteen whites) and five hundred people injured.

Advertisement

Washington Park was not only an interracial battleground but also a place of intraracial confrontations. The behavior of African-Americans in public was often the subject of criticism from reformers in the black elite. The same Defender that advocated African-Americans’ rights also disapproved of “open-air performances of minstrelsy” in Washington Park and public baptism in Lake Michigan—practices from southern culture that were considered embarrassing in the North. The Defender targeted Washington Park in particular for its Sunday School Baseball League games, ruined by “disgraceful and unchristian fight[s],” and tennis played by postal workers and dining-car waiters wearing their uniform or no top shirt. “Tennis is strictly a gentleman’s game,” proclaimed an editorial in 1922, and “no gentleman of any breeding will appear on any tennis court without a top shirt.”

By 1929, when the Great Depression started, Washington Park was used exclusively by the black community. On an August day in 1930, 12,000 people gathered there for an enormous picnic and parade to celebrate Bud Billiken, a fictional character standing for the pride and optimism of the black community, who had been created in 1921 by Robert S. Abbott, the founder and publisher of the Defender. It was no coincidence, McCammack points out, that this event was initiated at a time when the black elite looked to maintain the cohesion of the community, which had been severely hit by the onset of the Depression. African-Americans were often the first to be laid off from their jobs, since most of them worked in industries vulnerable to the economic crisis. They lost even the jobs that were traditionally given to African-Americans, such as porter, elevator operator, and janitor, so that by 1932 the unemployment rate of African-Americans had reached 50 percent, while for whites it was 30 percent. This also affected the black upper classes, whose businesses depended on the earnings of the black lower classes. By the end of the month that the first Bud Billiken parade took place, all the banks in the Black Belt were closed.

During this tumultuous decade the African-American working class could count on little support in defending its rights. One voice that did protest against the evictions of unemployed African-Americans who could no longer pay their rent was that of the Communist Party of the United States, established in Chicago in 1919. Even though black Chicagoans counted for a small share of the total members in the city (412 at its peak in 1931), the party sympathized with African-Americans, seeing them as “true proletarians, associated with essential heavy industry.” For their rallies, which could mobilize tens of thousands of people, the party also chose Washington Park. At a time when few black Chicagoans could afford to spend money on entertainment, Washington Park was the most prominent free public space for people of color. “What had been violently contested racial space during the Great Migration had become virtually uncontested African American space during the Great Depression,” writes McCammack.

Another “landscape of hope” that thrived because of segregation was Idlewild, the resort established in 1916 in Michigan by a group of white developers—two of them former members of the Ku Klux Klan—looking to attract the African-American upper class. Affluent African-Americans had the means and the desire to travel for leisure, but the white resorts around Chicago were as inaccessible to them as they were to the African-American working class. Black entrepreneurs founded black resorts on the East Coast starting in the 1890s; their popularity, McCammack suggests, inspired white developers to create Idlewild.

Within a decade of its opening, thousands of plots were sold and hundreds of vacation homes were built by visitors from Chicago and the entire Midwest. Most of the Chicago black elite were among the buyers: Jesse Binga, the founder of the most important bank serving blacks in Chicago; J.C. Austin, the leader of the Pilgrim Baptist Church; Oscar de Priest, Chicago’s first black alderman; and Robert Abbott, the publisher of the Defender. Yet to the vast majority of African-Americans Idlewild remained an inaccessible “landscape of hope.” McCammack’s book ends in 1940, so he does not mention that after segregation was banned by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 Idlewild’s clientele moved to resorts previously frequented by whites, leaving America’s “Black Eden” to sink into decay.

If Landscapes of Hope alludes to the effect of segregation on galvanizing the black community, Ben Austen’s High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing highlights its corrosive effect and the demise of public housing. How did places welcomed with such enthusiasm by their initial inhabitants turn into the most emblematic examples of gang violence in the United States? How was it that despite this stigma, Cabrini-Green survived until 2011, when it was finally torn down?

Advertisement

The first phase of the project was completed in 1942, one year after the United States entered World War II, and consisted of 586 units divided into fifty-four two- and three-story row houses, named after an Italian-American nun, Francesca Cabrini, the first American to be canonized. The project replaced the notoriously violent Little Hell, a neighborhood on Chicago’s Near North Side where the Italian and Irish mafias were born, and was meant to house mostly whites (75 percent). More homes were built after the war: in 1958, the Cabrini Homes Extension was completed (1,925 units), followed by the Green Homes in 1962 (1,096 units), named to honor William Green, a prominent Chicago union leader.

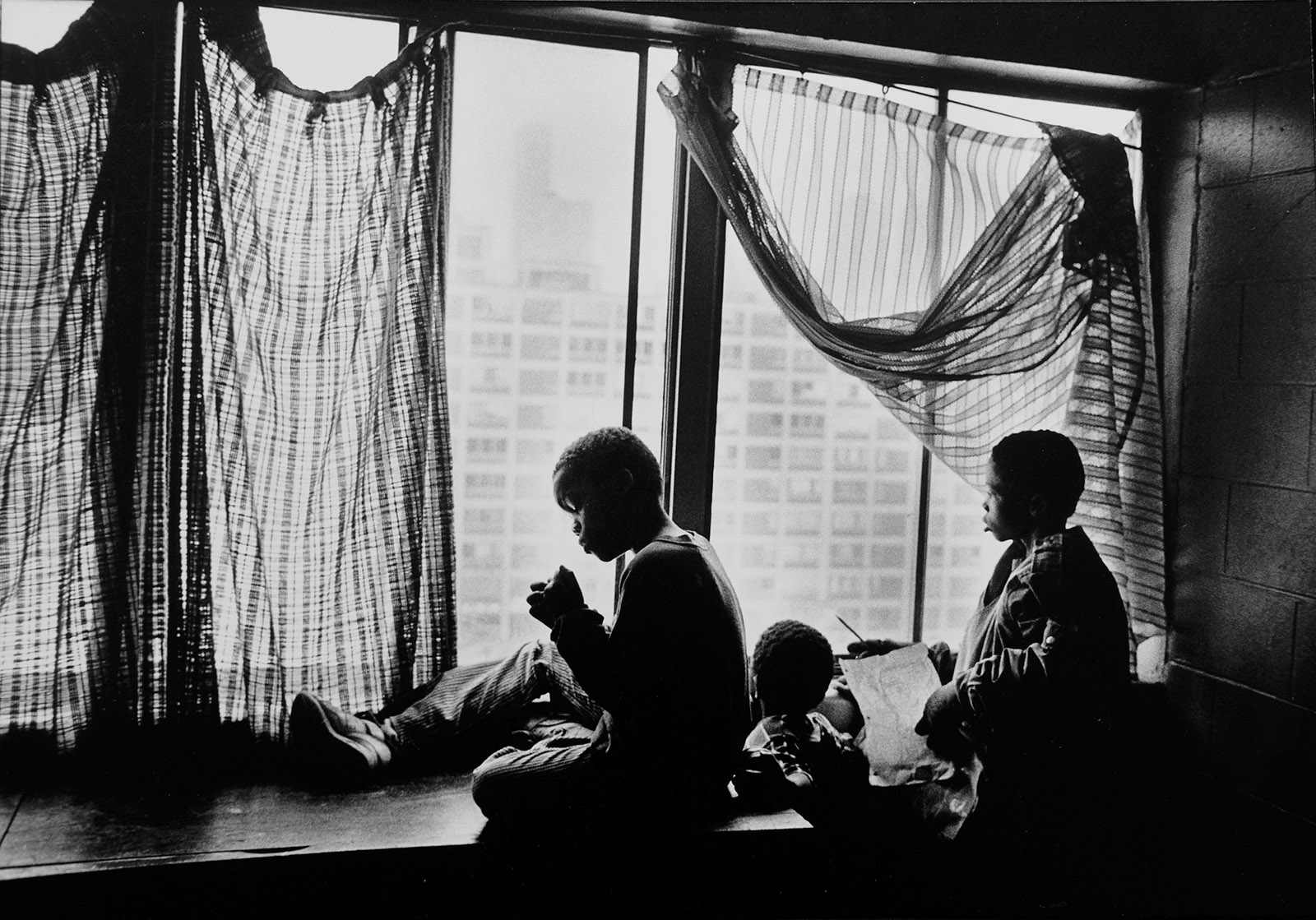

Based on the modernist urban design popular at the time, the two postwar projects were towers in a park. For the Cabrini Homes Extension, sixteen towers of a maximum of nine and sixteen stories were proposed. Due to budget cuts, fifteen towers of seven, ten, and nineteen stories were built instead. To reduce costs even more, they had a nearly identical design: red bricks framed by an exposed white concrete structure, which earned them the nickname “the Reds.” The project was praised for using only 13 percent of the site, leaving the rest for plazas and lawns. The Green Homes added eight more towers of fifteen and sixteen stories, finished with beige concrete sectionals and exposed concrete frames. They came to be known as “the Whites.” The three-, four-, and five-bedroom apartments, equipped with a refrigerator, stove, and hot and cold water, were a far cry from the crowded tenements they replaced, which had shared toilets and no running water or electricity.

With the improvement of living conditions, the city also hoped to eradicate the crime that was plaguing the slums. But despite the city’s expectations, crime returned to the former Little Hell area. Much of the blame has been attributed to the architecture of the buildings themselves. Their sheer height coupled with poor maintenance proved a recipe for disaster. Staircases with no direct light turned dark as soon as light bulbs broke or were stolen. Corridors were filled with litter when garbage chutes got clogged. Elevators shut down after children climbed on top of the cars. Top-floor apartments suffered from leakage from the poorly constructed flat roofs. And from the safety of the top floors, gang-affiliated snipers shot randomly at passersby, including police officers.

Still, in the end the problem was social. When the Cabrini Homes were completed, the complex’s residents were 80 percent white and 20 percent black. The white families that lived there were uncomfortable in a mixed community and asked the CHA to group and segregate the African-American renters inside the complex. Even the local priest Luigi Giambastiani (who had suggested that the public housing complex be named after Mother Francesca Cabrini) expressed his indignation that white and black people had to live together: “This is being resented by all and I must add, in order to be candid with you, that I don’t like it either.”

After the Cabrini Homes Extension was built, the demographics of the complex reversed: it became 80 percent black and 20 percent white. Since African-American families were generally poorer, they had priority in receiving an apartment at Cabrini-Green. White families left at the first opportunity. Like Washington Park, Cabrini-Green became an area exclusively for African-Americans, segregated from the white parts of the city. The fact that single parents were eligible for benefits caused the men to live away from their families and move back to the South Side in search of work, leaving women to take care of children (often more than ten) on their own. For men who had jobs and stayed with their families, rents were increased to the point that they could no longer afford to live in public housing. In the late 1960s, out of the 20,000 people who lived at Cabrini-Green, 14,000 were under seventeen. Soon their outdoor games were turning into violent territorial disputes, while some joined gangs. The decaying Cabrini-Green towers reflected the reality of public housing throughout Chicago but not the entire country, since, as Austen points out, three quarters of the public housing stock in the United States was not high-rise.

The story of Cabrini-Green is very much like that of the infamous Pruitt-Igoe projects in St. Louis, which also declined into poverty and crime. So why did it take so long for it to be torn down, as Pruitt-Igoe had been in the early 1970s? “The idea of demolishing Cabrini-Green seemed like a political as well as a practical impossibility,” Austen explains. Chicago’s officials could not find a way to house its 15,000 poor black residents. Instead, the city poured money into hasty renovations, then declared them successful by tweaking statistics about crime and employment. Again, lack of maintenance made these efforts futile. With the complex fought over by Chicago’s most feared gangs—the Black Disciples and the Gangster Disciples, the Vice Lords, and the Cobra Stones—crossing the space between the towers became a game of Russian roulette. “A thousand windows rising up, and in any one of them a heedless seventeen-year-old with a rifle could smudge you out as he would an ant,” writes Austen.

Elderly tenants moved out of Cabrini-Green and poorer tenants, often ex-convicts, came instead. By the 1970s three quarters of the households were on welfare and had a single parent. Without any job prospects nearby and confined to the complex by the police, they were often left with the choice of either consuming or selling drugs—a curious kind of circular economy. Time and again, police were sent in to sweep the buildings in search of guns and drugs. “We have to have a war here, and we have to go after them the same way they go after innocent people,” declared Richard M. Daley, the longest-serving Chicago mayor, after seven-year-old Dantrell Davis was shot dead in front of his school. But guns and drugs would always make their way back to Cabrini-Green, and with every raid fewer were confiscated. As with the renovations, the raids exhausted the CHA’s budget. One single sweep, Austen estimates, cost up to $175,000.

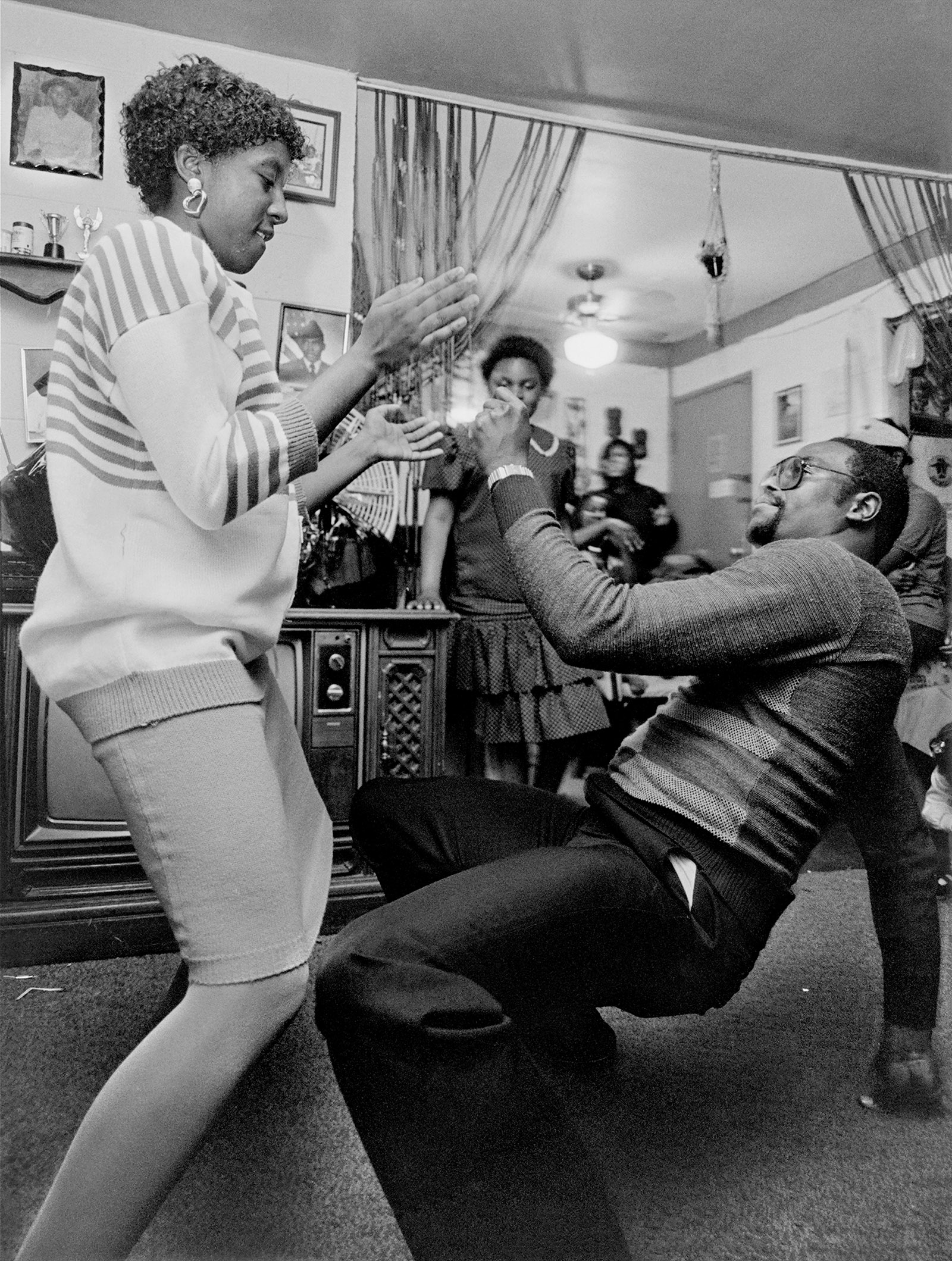

Still, Austen contends that life at Cabrini-Green wasn’t as gloomy as the press made Americans believe. Despite the crime, some apparently loved living there: adults, because they could rely on their neighbors and had their family around; teenagers, because they could socialize freely and make easy money (from illegal activities). Austen’s book is full of such stories. We read about Dolores Wilson, mother of five, who started a pen-pal program for prison inmates and coordinated a residents’ initiative to rehabilitate and manage their tower, all while working full-time at the city water department. We read about Annie Ricks, mother of thirteen, who walked seven miles through snow on a December morning to Cabrini-Green and didn’t leave until she got an apartment. Twenty-one years later, also on a cold December day, Annie was the final resident to leave Cabrini-Green. We read about J.R. Fleming, an African-American who grew up in the suburbs and moved to Cabrini-Green to escape white persecution. Giving up the prospect of becoming a football player, he survived by bootlegging Chicago Bulls T-shirts and music, eventually becoming an anti- eviction activist.

These people hardly made the headlines. Instead, Cabrini-Green was used as a textbook case of the welfare state’s failings. In calls for the elimination of public housing and arguments for the cure-all power of the market economy, it was conveniently overlooked that only a quarter of public housing in the United States was in the problem-prone high-rises. Cabrini-Green’s fate was eventually sealed during the Clinton administration. Its high-rises were to be replaced with “human-scale” mixed-income developments like those in other cities. A win-win situation, supposedly: the influx of more affluent residents to the new buildings would break the concentration of poverty, while the publicly assisted residents would benefit from better-quality housing. Situated near the city center—unlike other public housing complexes built later—Cabrini-Green’s land was a not-to-be-missed opportunity for real estate investment. The two thirds of the former inhabitants who had to be relocated would get vouchers to help them rent market-rate housing.

Reality quickly demystified the blessings of the mixed-income development approach. For the “lucky” public housing families who moved to the new mixed-income development, life was far from easy. The project, named Parkside of Old Town, covered eighteen of the former seventy acres of Cabrini-Green and comprised 30 percent public housing, 20 percent affordable housing, and 50 percent market-price housing. Construction was planned in two phases. In 2006, two years before completion, the developer sold 70 percent of the market-price housing units, with condos starting at $300,000 and townhouses at $500,000. With the money from the presales, the developer built the entire first phase at once. Some people bought more than one apartment, hoping to make a profit from resale.

Then came the 2008 financial crisis. “Stuck with their bum mortgages…the owners came to resent the people who were ‘living for free’ beside them in nearly identical apartments,” Austen explains. Worried that their properties would depreciate even more, the owners (who could form owner associations, while the public housing families could not form tenant councils) adopted all sorts of regulations, going as far as to propose prohibiting pajamas in public spaces and banning garden gnomes. The CHA had its restrictions, too. If one member of a family ran into trouble with the police (even if not convicted), the entire family could be evicted. “You had to choose between your daughter who was caught smoking weed and a roof over your head,” Austen writes.

Most relocated families ended up in areas that were predominantly African-American and overwhelmingly poor, such as the South Shore, which accommodated more relocated families than any other neighborhood in the city. There they faced extreme hostility from the locals, who blamed them for the soaring crime rates throughout the city. In 2012, one year after the last Cabrini-Green tower was demolished, Chicago experienced the highest murder rate in the country (higher than New York and Los Angeles combined) and the highest in the city since the 1990s, when sentences for violent crimes were almost doubled by the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994. The relocations, Austen writes, “didn’t so much break up concentrations of poverty as move them elsewhere, making them less visible to the rest of the city.” Thomas Sullivan, a former US attorney monitoring the CHA’s Plan of Transformation, said, “The vertical ghettoes from which the families are being moved are being replaced with horizontal ghettoes.”

High-Risers is in almost every respect the opposite of Landscapes of Hope. The passages about Cabrini-Green residents, interspersed among chapters about the history of the projects, take the reader into the drama of life in African-American communities. Unlike McCammack, whose book is exclusively based on diligent archival research (out of 350 pages, one hundred are endnotes), Austen combines archival work with empirical research. The hundreds of hours he spent interviewing the residents of Cabrini-Green often give his prose the depth of a novel.

The story of Cabrini-Green makes one aware of a curious paradox. What applies to the optimistic creation of Cabrini-Green applies every bit as much to its demolition: both serve as uncomfortable reminders that the dream of equality—even fifty years after the civil rights movement—is far from available to all Americans.

This Issue

September 27, 2018

Aquarius Rising

Missing the Dark Satanic Mills

Tenn’s Best Friend

-

*

For more on de facto and de jure housing segregation, see Jason DeParle’s review of Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (Liveright, 2017) in these pages, February 22, 2018. ↩