On January 30, 1972, Gilles Peress was in Northern Ireland photographing a march against internment without trial when British soldiers shot dead thirteen men (a fourteenth died later in the hospital). The event came to be known as Bloody Sunday, and it marked a turning point in Irish history, resulting in direct rule from Westminster and a section of the populace being driven away from the concept of civil rights and into supporting the IRA. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s Peress returned sporadically to Northern Ireland, and Whatever You Say, Say Nothing (the title is from an IRA poster, and was made famous by a Seamus Heaney poem) presents his work from those years. Volumes 1, 2, and 3—the first two hardcover volumes measuring fifteen inches across and together comprising more than a thousand pages of photographs, and the third an “almanac” of accompanying texts, half as wide but just as thick, called Annals of the North—are packed in screen-printed cardboard boxes and delivered in a screen-printed tote bag. It is expensively and beautifully done.

Peress, who joined Magnum Photos in 1971 and has twice served as its president, is professor of human rights and photography at Bard, and senior research fellow at the Human Rights Center at Berkeley. His awards include a Guggenheim, NEA grants, and the International Center of Photography Infinity Award. He styles himself as not being interested in “good photography”: he says he is “gathering evidence for history,” and his previous books include The Graves: Srebrenica and Vukovar, The Silence: Rwanda, Farewell to Bosnia, and Telex Iran.

In Annals of the North, Peress writes that in Northern Ireland his “intent was to describe a totality in all its simultaneities”:

I wanted to describe EVERYTHING—and yes, maybe this was a folly doomed to failure. I tried every possible visual strategy known to me at that time to DESCRIBE: I tried multiple camera angles, camera formats, day, night, rain and sun, and I went back again and again to the same places, the same street corners over and over, hundreds of times over the years.

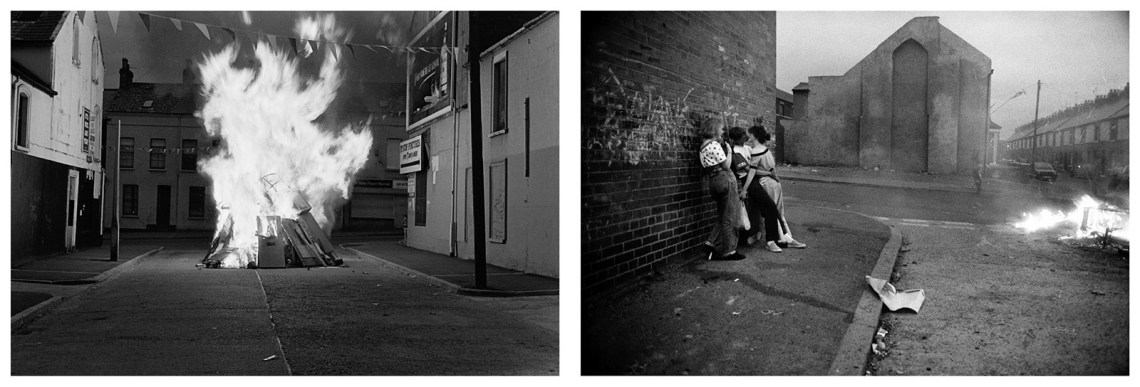

What he didn’t try much of was color film: among these 1,056 pages, there are only thirty-one color photographs. You come away from the books with a sense of monochrome griminess and half-light, of all the varieties of gray—concrete, ashes, lead-colored skies. The photographs span from 1971 to 2006, but the bulk of the pictures are from the 1970s and 1980s, and the stasis of those decades is distressingly apparent here.

Amid the shades of gray, the obdurate darkness of blood occurs occasionally, shockingly, and the most shocking, though familiar, work here relates to Bloody Sunday. Peress arranged the pictures in a section called “Days of Struggle.” (“Struggle” was the Irish Republican word for their armed campaign.) They seem like newspaper photos, the quality blurred, rushed, urgent, and the images are extremely powerful and distressing: a mass of men using a sheet of galvanized roofing as a makeshift shield, injured men lying beneath the graffitied imperative to “JOIN YOUR LOCAL IRA UNIT,” the body of Barney McGuigan (though not named), who’s been shot in the head by the British army, a priest giving McGuigan the last rites.

Most of the thousand-odd photographs focus on similar territory, though among the street riots, the petrol bombers, the adolescent soldiers, the shaggy teens in Seventies denim, the men in balaclavas with Kalashnikovs, the bombed-out wastelands and bonfires, there are moments when a different reality creeps in: boys at a beach, a day at Ballycastle fair, the Croagh Patrick pilgrimage, a cattle market, pigs in yards, Friesians dappled with shadow from hedgerows (“camouflaged cows,” Peress writes). But even the “fictional” day (as Peress terms it) in the country gives way to “shards of anger” when he encounters an IRA-made sign commemorating two men, “B.Burns” and “B.Moley,” “killed on active service on 29th Feb 1988.” (The monumental history Lost Lives1 reveals that they were killed when a bomb they were making exploded prematurely in a barn.)

What stands out in Peress’s work is its expressive detail—the feet of four men in a row standing on the edge of a pavement, all with the same slip-on loafers and white socks, or a boy shielding his eyes against the sun, unknowingly repeating the gesture of a woman who might be his mother, standing far behind him. But the grim imagery is relentless. Graffiti, desolate lots, empty back streets, barbed wire, human subjects tending to their pain or suspicion. Those were bad years. A few of the pictures spark with unexpected combinations and angles: to the right is a man leaning in a doorway, looking for all the world like a country farmer, while in the foreground we see huge, shiny Doc Martens and jeans, the lower parts of a man standing on a gatepost, and up in the far left corner the ever-present army helicopter hovering in the sky.

Advertisement

A note on the history of Northern Ireland may be useful. Ireland was partitioned in 1921 into Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland, which became, in 1922, the Irish Free State, and in 1949 the Republic of Ireland. Northern Ireland had a Protestant and Unionist majority who wanted to maintain ties to Britain, and a significant minority of Catholics and Irish nationalists. Southern Ireland had a Catholic, nationalist majority who wanted self-governance or independence. Following partition, discrimination against Catholics in Northern Ireland was widespread in housing, gerrymandering, employment, and voting rights: in order to vote one had to be a house owner, or head of a household, which disproportionately disenfranchised Catholics. In 1967 a diverse group of reformers created the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) to protest discrimination and campaign for civil rights for all. It was formed not by Republicans—those who believe in violence in order to bring about a united Ireland—but by nationalists, who believe in Irish unification but reject violence.

NICRA demanded changes in voting and in the allocation of houses and jobs, and the disbandment of the B Specials, a Protestant reserve police force that had a history of brutal behavior. Their campaign imitated tactics from the American civil rights movement, and in 1968 NICRA held its first protest march. Other groups (People’s Democracy, the Derry Housing Action Committee) formed and mass unrest followed. In mid-1969 the prime minister of Northern Ireland, James Chichester-Clark, announced the introduction of “one man, one vote,” the movement’s central demand, but on August 14, 1969, after rioting spread and culminated in the Battle of the Bogside in Derry, the British army arrived in Northern Ireland.

The army arrived initially to protect the Catholic population from sectarian retribution, but relations deteriorated quickly. Confrontations and civil disobedience became more frequent. The situation became polarized and militarized: in these circumstances the Provisional IRA could assume a leading role and, particularly after Bloody Sunday, emerged as the dominant force. Irish Republicanism became the principal political position for those seeking radical social change.

Yet the actual conditions altered a great deal in ways not apparent from photographs of riots or IRA volunteers or abandoned streets: by the mid-1970s a series of reforms ensured that NICRA’s original aims would largely be achieved. The 1971 Housing Executive Act dealt with discrimination in the allocation of housing. The 1971 Local Government Boundaries Act provided for a commissioner to deal with boundaries for district councils and wards, to stop gerrymandering. The Fair Employment (NI) Act of 1976 set up an agency to promote equality and opportunity for employment and eliminate unlawful discrimination on the grounds of religion or politics. Nevertheless, Northern Ireland had stumbled into the morass of the Troubles, where it would be stuck for decades.

In his 1972 essay “Photographs of Agony,” John Berger discusses Don McCullin’s war photographs from Vietnam, which are unsparing, showing up close the cost of war: disfigured corpses, wounded soldiers and civilians. Berger argues that these pictures of suffering—though their subjects are the consequence of political decisions—go beyond the political, and become “evidence of the general human condition.” They accuse “nobody and everybody.” Peress, for his part, is keen for his photographs to accuse somebody, to stand within a political setting, within “the structure of history that he was trying to articulate”—to quote Chris Klatell, the American lawyer and Peress’s close friend, who wrote most of the text in Annals of the North—and Peress’s “structure of history” is one entirely sympathetic to violent Republicanism.

It’s hard to know what to make of the intensive scaffolding that is Annals of the North, shadowing and obscuring, as it does, the edifice beneath. Susan Sontag thought photographs strong as evidence but weak in meaning, and I suppose Annals of the North is an attempt to ensure that the photographs are packed with meaning. Images that might have been able to evoke or suggest are now required to tell or explain. Annals contains short “chapter notes” by Peress, commenting on the images in volumes 1 and 2, but it’s mostly a sprawling compendium of Klatell’s trawling of the archive, his retelling of Peress’s stories, and his own meandering and skewed thoughts on Northern Ireland.

In the chapter notes, Peress writes a long (free verse?) recounting of his engagement with the two British government inquiries into Bloody Sunday, the 1972 Widgery Inquiry (which he rightly calls the “whitewash of Ted Heath’s government”) and the subsequent Saville Inquiry, ordered by Tony Blair in 1998. The Saville Inquiry requested Peress’s negatives so they could scan them in high resolution

Advertisement

to establish the truth. Was there an IRA gunman in that crowd?

Was there a gun? (Maybe that last part is in my head)

In any case I realize they have no intent to establish the truth:

That with the blessing of the government and the Crown,

One Para killed 13 unarmed civilians in cold blood.

They are still looking for the god damned gun that will exonerate them of the crime,

Of the murder

Verbatim (with a heavy French accent): No, never. Go and fuck yourselves.

The photographs corresponding to Peress’s notes on Bloody Sunday are of documents from the inquiry: a map of Peress’s route that day; part of his witness statement; strips of his negatives; X-ray diagrams of the trajectories of bullets as they passed through the victims John Young (a seventeen-year-old shop assistant, shot while attempting to help another teenager who’d been shot), William Nash (a nineteen-year-old dockworker whose father saw him being shot and went to help him, before being shot himself), and Michael McDaid (a twenty-year-old barman who was shot near a barricade after escaping from an army vehicle); soldiers’ log sheets claiming they had been fired on; the heavily redacted witness statement of an informant who claimed the IRA “were planning to attack the army”; photographs of the crowd, rioting; close-ups of hands, feet, the shattered head of a man bleeding out on a pavement, a hand waving a white handkerchief…

The Saville Inquiry, which lasted twelve years and cost more than £400 million, resulted in a 2010 report that concluded that British paratroopers “lost control,” shooting fleeing civilians and those who tried to aid the injured. The violence was not found to have been premeditated, though the inquiry did conclude that British soldiers had lied in their efforts to hide their acts, that none of the shots fired by soldiers were provoked by stone throwers or petrol bombers, and that the civilians were not posing any threat. The British prime minister, David Cameron, apologized for the “unjustified and unjustifiable” killing of the thirteen men. (The fourteenth who had been shot died four months later in the hospital, and though his death was formally ascribed to an inoperable brain tumor, many consider him the fourteenth victim of Bloody Sunday.)

After extensive legal arguments and appeals, only in 2019 was a former member of the Parachute Regiment, Soldier F, charged with the murders of James Wray and William McKinney, as well as five counts of attempted murder that day. These charges were withdrawn in July 2021, following the collapse of the trial of two other former British soldiers charged with murdering the IRA leader Joe McCann in Belfast in 1971. (A judge found that statements given by soldiers to the Royal Military Police in 1972, which were relied upon in the McCann case, were inadmissible because of how they were obtained.) Given the similarities, the Public Prosecution Service of Northern Ireland reviewed the case against Soldier F and, concluding there was “no longer a reasonable prospect of key evidence…being ruled admissible,” dropped the charges. The situation is absurd: prosecution of a member of the British army has halted because its own investigation was so flawed.

There is no truth-and-reconciliation process in Northern Ireland, and the only long-term plan seems to be to wait until the perpetrators and victims die. The Northern Ireland Office, a British ministerial department whose mission is to “ensure the smooth working of the devolution settlement in Northern Ireland” (i.e., to keep Stormont, the Northern Irish parliament, functioning), recently proposed an amnesty for crimes related to the Troubles, a suggestion that was met with criticism from all parties in the North. Sinn Féin leader Michelle O’Neill tweeted, “There can be no amnesty for those who murdered citizens on the streets of Ireland and for those who directed them.”

But many people feel that Sinn Féin (the political wing of the IRA) is demanding a partial and selective approach to history. Republican terrorists—the IRA, the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA), and associated groups—were responsible for 58.8 percent of deaths in the Troubles, loyalists for 28.9 percent, and the security forces for 10.1 percent. The greatest single taker of life was the IRA itself, which accounted for almost half of all deaths: the IRA killed almost 1,800 people, including more than four hundred Catholics. The majority of IRA members who died in the Troubles were killed not by British forces but by internecine warfare or premature explosions or were executed by the IRA itself.

The Historical Enquiries Team, a unit of the Police Service of Northern Ireland set up in 2005 to investigate the 3,269 unsolved murders committed during the Troubles, was shut down in 2014 due to budget cuts. Some feel that if those who committed atrocities against Northern Irish civilians will not be prosecuted—some of the alleged and convicted killers are now government officials—the soldiers who murdered the marchers on Bloody Sunday shouldn’t be either.

Perhaps infected by this sense of thwarted reckoning, in Whatever You Say, Say Nothing, Peress and Klatell insist that Northern Irish history is an inescapable spiral. Peress organizes his photographs across “22 fictional days” to articulate the “helicoidal structure” of history “where today is not only today but all the days like today; days of violence, days of marching, of riots, of unemployment, of prison, of mourning, and also days of ‘craic’ where you try to forget your condition.”

In the section “The Book of Hours and Days,” Klatell presents events from 1689 and 1922 and 1998 as happening in some sense coterminously, depicting a country trapped in a time of no time, where nothing changes. History, to echo Joyce, is the nightmare from which we can’t awake. The effect of the anachronistic presentation of the photographs as all belonging to “22 fictional days” is to disfigure actual history, which is stubbornly real to the people who lived it.

Apart from photographers, those acknowledged by Peress for “their hospitality, generosity and advice” are nearly all IRA members and Republican activists: the Duffy family (identified in the “Cast” chapter as “led by Ann, a former Republican prisoner” with whom Gilles Peress lived in the 1980s), the Donaldsons (as in Denis, Peress’s “close friend,” an IRA volunteer, Sinn Féin administrator, and, it turned out, a British spy), Tom Hartley (a Sinn Féin mayor of Belfast), Danny Morrison (the long-term publicity director for Sinn Féin)…

Klatell’s wife’s family also makes the “Cast” list, an abbreviated dramatis personae of a thousand years of history. He’s married to Fiona Doherty, a Derry native whose father’s work with DuPont meant she moved to the US as a teenager; she is now a criminal law professor at Yale (and “served as the conscience of the North,” according to Klatell, in the making of the book). We learn the Dohertys are “a sprawling Catholic clan originally from Donegal with branches throughout the North, many only distantly related…. If someone is Catholic and from Derry, his or her gran is likely to be a Doherty.”

Klatell’s commentary often has this rambling, excitable, personal flavor, and though Annals of the North is wide-ranging in some ways and often surprising, thanks to its collage-like, random structure, it’s also, as you might imagine from the close friendship Peress had with IRA volunteers, deeply partial, and by turns incomplete, ill-informed, outdated, and patronizing.

Klatell dutifully follows Peress’s sympathies, though he seems less enamored with casual glorifications of murder: Klatell recounts Peress describing how, back in 1985, Daithi de Paor, an IRA man, had told him a story of the IRA bombing a costume store: “For some reason, or maybe for no reason, the Volunteers decided they had an issue with the Indian man who owned the costume shop” and decided to blow it up. After setting a bomb on the counter they drove away, but saw in the rearview mirror “the fucking Indian guy, calmly carrying the bomb out of his shop and chucking it into the street.” So the following week they went into the shop, “froze the owner at gunpoint, and glued the bomb to the counter. Then they all stood round in awkward silence, holding the bomb down, waiting for the glue to dry.”

After recounting this story, Peress laughed:

No one else did. That’s a terrible story, they said. What happened to the poor Indian man who owned the shop?

Gilles looked around in puzzlement. “That story wasn’t about the man who owned the shop,” he said. “It was about the glue.”

Realizing that murdering an immigrant “for some reason, or maybe for no reason,” might strike readers as despicable, Klatell tries here to put some daylight between himself and Peress, though with its black humor, casual gangsterism, and purposeless violence this anecdote is somehow one of the truest things in the book.

Klatell does not in general raise awkward questions about the book’s overwhelming narrative of Republican heroics, and he can be surprisingly loose with the facts. In another essay he describes Peress photographing an IRA funeral:

1985 was a gruesome year, a shoot-to-kill year, a year when the state’s forces abandoned the exhaustingly blunt instruments of the law for the short, sharp crack of bullets.

One day during that brutal summer word arrived in Derry about three Volunteers who had been executed the night before in a field outside Strabane. They’d been moving a cache of arms when the army surprised them. They’d immediately surrendered, and then they were killed.

To locate the incident Klatell refers to, I looked at the killings from the summer of 1985. From May 1 to the end of September that year, nineteen people were killed in the Troubles. Sixteen were shot or blown up by the IRA (one British soldier, six Protestant policemen, one Catholic policeman, two Protestant civilians, five Catholic civilians, and one IRA man who accidentally killed himself with a grenade launcher), two Catholics were killed by the INLA, and one (a Protestant petty criminal) was killed by the Ulster Volunteer Force.

The incident Klatell must be referring to happened in February 1985: five IRA men set up an ambush by a road in Tyrone and waited for a vehicle belonging to the security forces to appear. After several hours, when none did, the ambush was abandoned and two of the men went home. The other three were returning the weapons to the arms dump, each carrying an automatic rifle, when three British Special Air Service soldiers hidden in the field opened fire on them and killed them.

To describe the killings as an execution might be legitimate (forensics showed the IRA men had not fired, though one soldier claimed they heard someone say, “They’re over there—get them”), but there’s no evidence either way as to whether the dead “immediately surrendered,” and to characterize the incident, as Klatell does, as “moving a cache of arms” shows that his lack of interest in the complications of reality extends beyond the date of the incident to its actual circumstances. (In the notes, Klatell reveals his source: “A Republican account of the killings can be found in the February 23, 2015, issue of An Phlobacht,” the Sinn Féin newspaper.)

Klatell cannot imagine a Protestant sensibility that is anything other than grotesque. Orange marches are “sadistic victory parades of the Prods, ecstatic in their imposition of humiliation.”2 To many people, not just Protestants, this might seem not only a caricature but a gross misrepresentation. Ulster Unionist MPs at their annual dinner are presented by Peress as literally negative images, their heads black and ghoulish. Compare that with the photograph of Gerry Adams frolicking with kids in a bouncy castle, although there’s no room to mention Adams’s admission of knowing about his brother Liam’s pedophilia and still allowing him to work at a youth center in Gerry’s own constituency. (Liam Adams was later convicted of repeatedly raping his daughter when she was between the ages of four and nine.)

Most of the pages in the Annals have no numbers, and it is impossible to navigate the book easily. Perhaps this is deliberate. It makes cross-checking sources almost impossible. In relation to Denis Donaldson, for example, pages that appear to be from legitimate newspaper sources are presented with the headings “The Facts,” “The Context,” “The Myths,” and so on, though only by counting forward thirty-eight pages from the last page number and checking the notes at the back is it possible to ascertain that the documents have in fact been “provided by and courtesy of the Donaldson family.” No other source for them is given.

Klatell and Peress’s attempts to situate the photographs in Peress’s “structure of history” leads to occasional absurdities. Some are distasteful, some ignorant, some inadvertently comic. In the “Cast” chapter, for example, Francis Hughes, a hunger striker, is gushingly described as

a charismatic and tenacious young member of the Provisional IRA referred to as the “most wanted man in the North of Ireland.” The authorities captured him in a ditch after a shootout with the sas, looking like a rock star with dyed blond hair even though he was gravely injured.

What Klatell doesn’t mention in this lively biographical sketch is that Hughes was convicted of killing three people, and reputedly killed more than a dozen, with some sources alleging he was responsible for at least thirty deaths. Among the deaths he was linked to were those of a seventy-seven-year-old grandmother and a ten-year-old girl. For many people in Northern Ireland, this kind of encomium to those who killed their relatives is not just embarrassing but deeply offensive.

And tellingly, Hughes was not called the “most wanted man in the North of Ireland,” as the book’s quotation marks suggest. Those who wanted to arrest Hughes were the security forces, and they referred to him as the “most wanted man in Northern Ireland.” The book’s “Languages” section, a glossary of events and terminology, states that

the phraseology “North of Ireland” indicates the speaker believes in a united Ireland and tacitly or explicitly disapproves of the union with Great Britain, whereas Northern Ireland can be used neutrally (it is the internationally recognized name for the territory) or affirmatively to embrace the union.

Klatell and Peress eschew what they define as the neutral term and use “the North of Ireland” throughout, even when, as with Hughes, it leads to senselessness.

Klatell continually repeats the Sinn Féin/IRA line. Here’s the definition provided for Direct Action Against Drugs (daad): “An operation by the Provisional IRA to combat drug use and anti-social behavior in Catholic neighborhoods, both to uphold the social order and to cut off opportunities for infiltration by Crown forces.” Well, yes, that’s what the IRA said, but let’s look at what they did. daad was a cover to allow the IRA to continue operating after they’d declared a cease-fire in 1994.

Take the case of Paul Devine, shot six times in the back by the IRA as he walked to his car on December 8, 1995. Devine was a former IRA member who’d been expelled for keeping the proceeds of a robbery. (He’d recently been released from prison after serving three years for handling stolen goods.) Or Francis Collins, a father of five and former IRA member shot ten days later, on December 18, in the fish-and-chip shop he and his wife had recently opened. Two men entered through the back door, and one shot Collins in the knees with a handgun before shooting him in the chest. daad claimed responsibility, though Collins’s wife said, “I firmly believe that he was murdered as a direct result of a personal vendetta by individuals from within the republican movement.” The police told the inquest: “There is no evidence that the deceased was involved in drugs.”

What is Klatell, a lawyer, thinking when he parrots the idea that daad was upholding “social order”? Nine days after Collins was murdered, on December 27, a small-time drug dealer named Martin McCrory was shot dead through the window of his living room. His three-year-old son, sitting beside him, was also hit by a bullet. Gino Gallagher, a member of the INLA, allegedly took part in the Devine murder to allow the IRA to claim it was upholding its cease-fire, and was arrested for it before being shot dead a month later, in January 1996.

Fallout from the subsequent feud led to many more dead, among them a nine-year-old Catholic girl, Barbara McAlorum. The dead girl’s father said:

She was only an innocent little child. They are nothing but cowards, complete scum…. My wife was screaming, “Get up, Barbara, get up,” but we could see she was dead. Her head was lying in the jigsaw puzzle I bought her.

But one can imagine Peress looking up here “in puzzlement,” explaining that the story isn’t about Barbara McAlorum. Though Seamus Heaney is invoked repeatedly in these volumes—he provides an epigraph (along with Terence MacSwiney and Bobby Sands), and photographs of his Sweeney Astray are included—what is missing is Heaney’s sense of a morally complicated place, a location where no one was exactly right but some were clearly wrong: “My sympathy was not with the IRA, but it wasn’t with the Thatcher government, either.”

Another American has written an engrossing, informed book, grounded in reality, about Northern Ireland, and it takes its name from the same expression as Peress’s book: Say Nothing (2018) by Patrick Radden Keefe. It wears its authority lightly and is heavily sourced and footnoted. While ostensibly telling the story of how Jean McConville, a Protestant mother of ten, was disappeared by the IRA on the orders of Gerry Adams, Say Nothing actually explains much of the Troubles, detailing, for example, Bloody Sunday, the hunger strikes, the Gibraltar killings, Michael Stone, the Denis Donaldson affair, the Boston tapes…. It’s a masterpiece, and one of the best introductions you’ll find to the twisted state of Northern Ireland.

Today, as Sinn Féin takes the lead in politics in the South, preaching a populist leftist gospel and promising solutions to everything from the housing crisis to investigations into the deaths at mother-and-baby homes, it’s important to also remember other, more recent deaths. Among Americans the list of useful idiots for the Irish Republican cause is long, and Klatell, though he has clearly steeped himself in the history and culture of the North, has also, in the end, let himself be a tool for violent Republicanism. He is attempting to cement a story that simply isn’t true, the reality being more complicated and demanding than his scrapbook admits.

It is, of course, possible to believe in the inevitability and desirability of a united Ireland without supporting or romanticizing Irish Republicanism. It is possible to think that partition was a disaster and that Northern Ireland practiced systematic discrimination against its Catholic minority for many years while also refusing to justify, glorify, or accommodate the horrific actions of Republicanism. That’s why the Social Democratic and Labour Party exists—to advocate for Irish reunification, though it has been largely eclipsed by Sinn Féin since the 1994 cease-fire—and why the sdlp’s John Hume, a Nobel Peace Prize winner, was an admirable moral leader while Martin McGuinness and Gerry Adams have the blood of thousands on their hands.3

It is also possible to think that the British security forces interned and tortured their own citizens in the 1970s and 1980s, that they authorized shoot-to-kill policies, and that Bloody Sunday was never properly investigated or concluded, without extolling or validating the destruction wrought by the IRA. (Another excellent, well-sourced, and definitive book is Anne Cadwallader’s Lethal Allies: British Collusion in Ireland (2013), about the collaboration between Crown forces and loyalist paramilitaries.)

It’s not a morally complicated position to think that killing people is wrong, regardless, and that what the people of Northern Ireland have had to witness and accept in the years since the 1998 Good Friday Agreement has been extremely difficult. Terrorists on both sides were released back into the community after serving only a year or two, and live side by side with the relatives of their victims, who see them alive and well in supermarkets and bars and waiting rooms while their own husbands or children or parents are still dead. Or see them in the government, appearing on television, endowed with well-paid jobs as special advisers or administrators.

In any event, Northern Ireland may be entering another paradigm altogether. Following the tensions of Brexit and the possibility of an independent Scotland, questions of allegiance and identity that the Good Friday Agreement had pushed off into the distance are being revived.4 The Northern Ireland Protocol in the Brexit withdrawal agreement avoided a hard border on the island of Ireland, but meant that Northern Ireland effectively remained within the EU’s single market and subject to its custom rules, and therefore created a regulatory border in the Irish Sea, between Northern Ireland and the rest of the United Kingdom.

There are currently food shortages and angry farmers, and increased trade between the Republic and the North. Under the Good Friday Agreement, a border poll on a united Ireland would involve referendums in both Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic, and the agreement states that a decision to hold a referendum rests with the UK secretary of state responsible for the region. While support for unification in polls has consistently remained below the triggering criteria, broader statistics suggest there might already be a Catholic majority in Northern Ireland, and though religious affiliation does not necessarily denote political affiliation, if the results of the 2021 census confirm such a situation, it would make calls for a border poll difficult to ignore.

It is vital, in an era when Sinn Féin is on course to become the largest party on both sides of the border, that we don’t forget the reality of what they did. It is not beside the point to ask about the Indian man blown up by the glued-down bomb, about the actual consequences of the “heroics.” While Peress sits at the bar, puzzled by questions about the victims (if the victims are those killed by the IRA), and Klatell is at his desk in his New York law firm, excitedly typing on his laptop that Northern Ireland is a “conceptual heart of darkness,” there are other images that deserve their part in the picture, not reproduced here: what’s conjured by this collaboration is partial, both in the sense of being prejudiced and in the sense of being fragmentary and incomplete, a bit like the jigsaw puzzle the nine-year-old Barbara McAlorum was doing when the IRA shot her in the head.

-

1

Mainstream, 1999. A mammoth undertaking, this landmark book by David McKittrick, Seamus Kelters, Brian Feeney, and Chris Thornton tells “the stories of the men, women and children who died as a result of the Northern Ireland troubles.” ↩

-

2

“Prods” is helpfully defined in the “Languages” section as “a pejorative term for Protestant(s).” ↩

-

3

The IRA never had popular support for its murderous campaign: in 1992, at the last general election before the cease-fire, not a single candidate of Sinn Féin’s was elected. They polled at 10 percent, far behind the Ulster Unionist Party at 34.5 percent, the SDLP at 23.5 percent, and Ian Paisley’s Democratic Unionist Party at 13.1 percent. ↩

-

4

See my “Blood and Brexit” in these pages, December 10, 2019. ↩