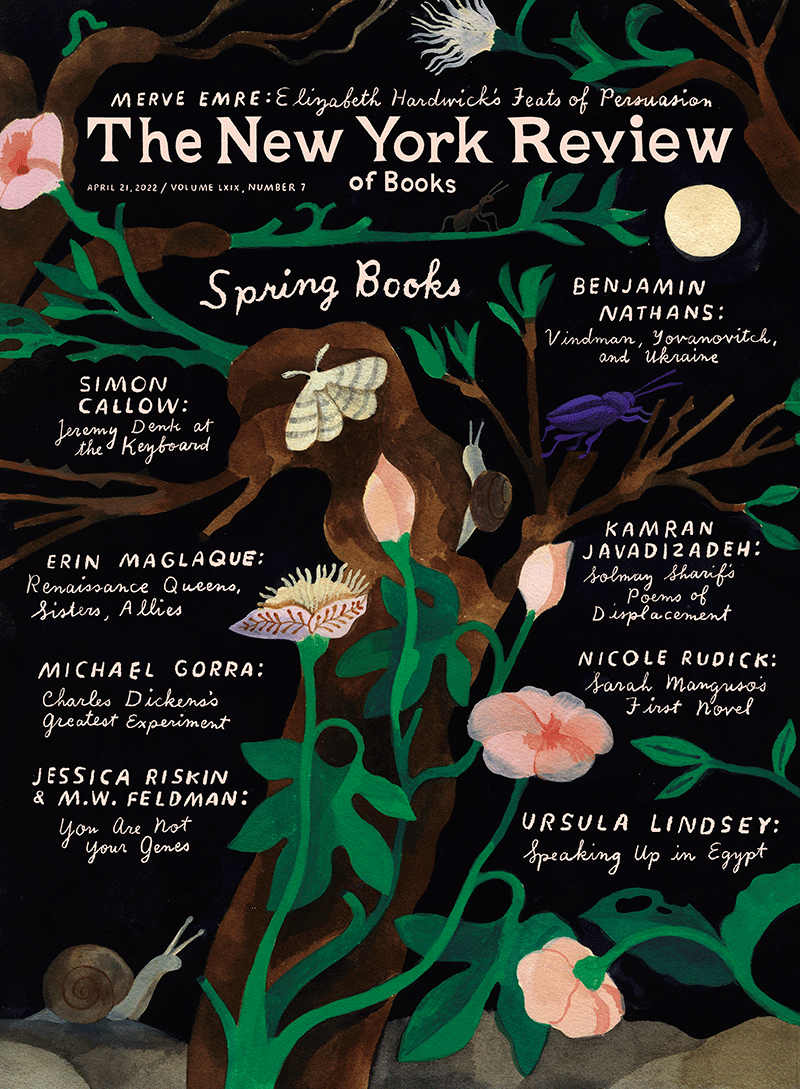

Reviewers of Sarah Manguso’s writing love to tally her words and pages—as is often the case for very short books (the “slim volume”) and very long ones (the “doorstop”), as though such extremes are feats beyond belief. Her work falls into the former category: books “brief as a breath” and “slim as a Pop-Tart,” written in a style that has been described as “fragmentary” and “aphoristic” (terms Manguso herself has disavowed), “with the precision of a miniaturist.” It is difficult to do a lot with a little, and Manguso, a poet as well as an essayist and memoirist, covers quite a bit of distance with a minimum of means.

Manguso’s prose is an uncommon mix of economy and obsession. Her first memoir, The Two Kinds of Decay (2008), distills a decade of intense treatments for chronic idiopathic demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy, a rare autoimmune disorder, into brief, forthright chapters that intimately illuminate the toll of chronic illness. In The Guardians (2012), she examines, through a series of vignettes, her friend Harris’s suicide, in order to give shape to her grief.

Ongoingness (2015) remarks on the voluminousness of Manguso’s diaries in fewer than a hundred pages; looking askance at the diaries’ 800,000 words, she admits to the impossibility of comprehending the passage of time. Ongoingness incorporates nearly as much white space as text, a formal structure that mirrors Manguso’s observations:

I’d write about a few moments, but the surrounding time—there was so much of it! So much apparent nothing I ignored, that I treated as empty time between the memorable moments.

She deepens her use of white space in 300 Arguments (2017)—a disjointed autobiographical meditation on big subjects such as ambition, beauty, time, depression, and failure—gathering into discrete entries of usually one or two sentences the quotable lines of an imaginary book, with all else excised.

Despite Manguso’s often fraught subjects, there is pleasure in following the path she cuts, particularly in The Guardians, in which the facts of what happened are intensified as her language becomes more abstract. When she thinks about her friend losing his life and identity at the instant of his suicide, the transition reads like a reverse miracle:

Harris met the train with his body, offered it his body.

The train drove into his body. It drove against his body.

It sent him from his body.

The conductor went down onto the track and touched the body and lifted and carried the body.

There was no need for a doctor.

The body was removed from the track and rested for two days without its name.

She tends to express thoughts as statements or assertions, and this gives her writing a feeling of tight certainty, sometimes even arrogance. Later in The Guardians, as she has a drink at a bar, she observes a man enter, swallow a shot without sitting down, and depart. Her assessment is instant yet speculative: “You know it’s a good bar when it attracts alcoholics with that level of familiarity.” In 300 Arguments she asks, “Am I happy? Damned if I know, but give me a few minutes and I’ll tell you whether you are.”

At times it seems as though Manguso’s linguistic constraints are a way of keeping a firm rein on the potential sprawl of the ideas her words illuminate, as if fewer words mean fewer opportunities for meaning to get out of control. “I always believed that the point of writing for an audience was to rescue the suicidal and to console the dying,” she wrote in a 2015 essay about motherhood.1 There isn’t much room for fallibility in that formulation.

Manguso’s first novel, Very Cold People, stays true to her style: in less than two hundred pages, it favors incident and mood over linear storytelling, with each individual paragraph surrounded by white space. Set mainly in the 1980s, it is an unsettled coming-of-age story narrated by a girl named Ruth, who lives in a kind of stasis, growing and maturing in an atmosphere of little warmth or nurturing. “I needed to stay approximate,” Ruth says. “No one could know what I cared about.” Her crucial relationships—with her parents and her female friends—surround her like the rings of electrons orbiting the nucleus of an atom, altering her but remaining apart.

Ruth is born in Waitsfield, a fictional small town on the outskirts of Boston and a place, we learn in the novel’s opening lines, to which her family doesn’t belong. For Ruth, an only child, it isn’t just that her parents are of a lower class than Waitsfield’s moneyed elite—“the first, best people,” such as Cabots and Lodges, whose three-hundred-year-old houses quietly boast the “historically correct paint color.” It’s that they are illegitimate, pretenders who scavenge at the dump and garage sales for cast-offs from their affluent neighbors. Her mother snips wedding announcements from the newspaper and affixes them to the refrigerator, as though the brides and grooms, who “sat on the boards of libraries and museums,” were friends of the family. Though Ruth can discern the superficiality in her parents’ behavior and in the community at large—she notices the sticky, fake snow sprayed on a lawn in spring for an ad shoot and recognizes the difference between the oldest houses and the newer, more expensive ones—she, too, falls for this perceived importance, “swoon[ing] over the girls and boys at school with names like Verity and Cornelius.”

Advertisement

Ruth sees that other kids wear the same shoes and expensive windbreakers as one another, and she envies “their clannish sameness.” She must make do with factory-second clothing and a Tropicana Orange Juice imitation of a Swatch watch. Her mother shops for groceries at the gas station and buys overripe produce picked from the “used food” section of the health-food store. Ruth enumerates these experiences without commentary, sometimes dissociated from the narrative. When she says, “Creditors called all day and into the evening. I had to pick up the phone and say that I was home alone,” the information is delivered in its own paragraph, without elaboration. Such lines recall the arrangement of 300 Arguments, as well as some of that book’s less successful entries: “I keep some desires unfulfilled for fear of losing all desire, but sometimes I need a break from them anyway.”

Manguso’s language can be exquisitely spartan and laconic. She describes the “soft fuh” of falling snow and how the light of a winter morning “spread like a watery broth over the landscape.” A synesthetic passage near the start of the novel is as florid as she gets:

Autumn brought with it the slap-clatter of crows, fire smells, leafy sweet-rot. New corduroys, cold air, brown paper grocery bags folded over schoolbooks. Writing on the first pages of notebooks, September 7. September 8. September 9, never sure how my handwriting should look.

Manguso captures the bewilderment of childhood in Ruth’s flat observations about situations she doesn’t fully understand, supplemented by feral imaginings. When a friend suggests miming sex between Ken and Barbie, Ruth wonders, “Would Ken lie stacked on top of Barbie, or would their only point of contact be their crotches as they balanced like acrobats?”

The novel is composed in the simple past tense, which creates the impression that Ruth is narrating her story as she moves through adolescence. After riding her bike up a hill and back down again, she concludes, “I knew that children were supposed to ride bikes for fun, and I dutifully played the part of a child having fun.” Some passages beggar belief, and seem calculated for an effect whose significance I can’t quite detect. It isn’t until the book’s very last paragraph that Ruth reveals that decades have passed, and she’s telling the story “some years into raising a child of my own.” This collapse of time often gives her childhood self a knowingness that is disproportionate to her age. When she is still young enough to be thrilled by the gift of a new Lite-Brite toy, she thinks, “My own girlhood felt like something from 1650 even when it was happening…. I spent those days feeling half-there, not quite committed to that life.” Only a few pages earlier, Ruth is playing in the garden of the local library, digging up earthworms and chasing beetles. She mistakes a pile of dog shit for dirt and plunges her hand into the “soft wet mound.” How is a child who is this ingenuous also articulate enough to express such a profound divorce from her own sense of being?

In elementary school, Ruth befriends a trio of girls—Amber, Bee, and Charlie. Their families fall at varying points on the economic spectrum: Amber’s father is a mechanic, Bee’s works in construction, and Charlie’s family is wealthy enough to have a housekeeper. Ruth remarks on Amber’s worn clothes, poor teeth, and free school lunches but also notes that they are both able to live across town from the kids of the Bannon Road projects, the lowest rung on the socioeconomic ladder. Later, Ruth learns from Charlie that even the Brahmins sort themselves according to worth, sifting out their poorer relations into lesser-thans.

Manguso’s descriptions of girlhood make for some of the novel’s best moments. The lead-up to puberty is adorned with friendship pins, heart-shaped stickers, and scented pencils: “Everything smelled like strawberries then—stickers, lip gloss, hair.” The girls’ easy familiarity, soon to be lost, begets an intimacy that Manguso voices collectively: “We were still young enough that our physical boundaries were permeable; we braided each other’s hair and knew the scents of each other’s scalps.” Manguso is wonderful at the slow fade of this blissful innocence, the way it is supplanted by dangers that infiltrate at the fringes of awareness:

Advertisement

Amber’s niece went to school with us for part of that year. When she introduced herself to Bee she said, I’m still thirteen. I know, I don’t look it, and the way she said it told us that she’d heard it so many times from so many men that it seemed as deeply a part of her as her own name. I remember there were so many horse chestnuts on the ground when she said it.

As the girls age into middle school, then high school, their different standings in this social order become more pronounced, and they drift apart. Ruth’s family moves to a better part of town, into a house formerly owned by Winifred Cabot Fish, a member of the storied Cabot family. “The house was cheap,” Ruth explains, “maybe because Winifred had died in it, and the family had wanted to off-load it quickly.”

In the attic, Ruth finds old photographic negatives of a man and a woman: “In one shot, they stand in tight embrace. It could have been Winifred and her husband, or it could have been her parents, or it could have been anyone.” The possibility inherent in these negatives is freeing to Ruth, and she begins to imagine, almost greedily, the various routes Winifred’s private life might have taken. The restraint that characterizes not only Ruth but the novel in general dissipates here. She becomes obsessed with Winifred—wondering if she might find strands of the woman’s hair in the house and thinking about how Winifred would use the sleeping porch during hot summer nights and walk along the brook in all kinds of weather. “I imagined her so completely that she became real,” Ruth says. Her fascination vitalizes the narrative, and the projection of Ruth’s fantasies onto another woman provides the most generous account of her inner yearnings.

Along with the negatives, Ruth discovers a pile of possibly bloodied clothing, which elicits a tangle of visions about enduring love, freedom, and sexual desire. Were the clothes Winifred’s memento mori of her love for her husband after his death? Or had she killed him so that she could be alone, free perhaps to pursue an unconsummated affair with the neighboring Lowell boy? “I wanted to believe that Winifred was a murderess because I wanted to have such power myself someday,” Ruth thinks. Her fantasy of murder is a desire for self-determination, and she keeps the details of this desire secret, “so that no one could contradict them and take them away.”

One summer afternoon, Ruth’s mother sprays her with the garden hose. “I laughed so hard I thought I might burst,” Ruth recalls.

Many times after that I asked my mother to spray me with the hose again, but she always said no…. I thought that maybe it was wrong to be that loudly happy, and that she was trying to protect me.

On the next page, walking home from elementary school on a winter afternoon, Ruth slips on the ice and is injured, but her mother refuses to come pick her up: “She screamed at me and said that she had never gotten a ride home from school.” In the next paragraph, her mother buys Ruth a fancy slip for her birthday party, then helps her young guests make construction-paper crowns.

Ruth’s childhood is punctuated by the contradictory behavior of her mother, an overweight Jewish woman who can’t forget the slights dealt her by her rich Catholic Italian in-laws and who feels patronized by her own wealthy family members even as she tries to curry favor with them. “She wasn’t classy like Aunt Rose or Uncle Roger,” Ruth says of her mother’s relatives, “but she wasn’t poor enough to be called poor. I carefully remembered all the names and how sophisticated all of them were, in descending order.”

According to Ruth, her mother thinks of herself as “the protagonist of everything.” She spies on people making out in cars, pointing them out to Ruth, and masturbates at the movie theater and while watching TV with her family, “making little sticky sounds with her mouth.” She sexualizes her daughter, too, begging her to wear a bikini instead of a one-piece swimsuit and responding approvingly when a cashier openly ogles Ruth’s body. Ruth guesses that her mother wants her to seem “already grown up,” though it’s unclear why.

A few pages earlier, Ruth is babysitting two boys. She spanks them after they barge in on her in the bathroom, and later soothes one who gets a nosebleed—she can’t locate herself on the spectrum of punisher and comforter and asks, “If I wasn’t their mother, was I my mother?” This cryptic line seems to suggest the process of becoming responsible for oneself, and it reminded me of a similar sentence from Kate Zambreno’s Green Girl (2011), a novel about another girl named Ruth and the fog of young womanhood. “Perhaps without a mother one can no longer be young,” Zambreno’s Ruth thinks. Both observations circle not only the thorny relationship of mothers and daughters but also the process of a girl becoming the primary subject of her own story.

When, about halfway through Very Cold People, an eleven-year-old Ruth thinks of herself as a child “whose capacity to receive love had been diminished,” I thought of Manguso’s concept of “extreme love,” from her 2015 essay on motherhood. Looking back on her pre-motherhood self, she wrote:

It seems obvious to me that my refusal to have a child was a way to avoid the challenges of extreme love, to avoid participating in dismantling the stereotypes that had brainwashed me.

The meaning of “extreme love” is fuzzy—is it a measure of trust or commitment, or that you’re willing to die for another person?—but two of its results, in Manguso’s conception, are a disposition “often mischaracterized as selflessness” (she describes the feeling of needing to care for her son as “an itch, an urge”) and a more developed sense of humanity. Not only that, but by “weathering trauma, practicing patience, being seasoned by love,” she has become, she says, a better writer and resolves to celebrate these newfound qualities in literature:

I want to read books that were written in desperation, by people who are disturbed and overtaxed, who balance on the extreme edge of experience. I want to read books by people who are acutely aware that death is coming and that abiding love is our last resort. And I want to write those books.

How does motherhood constitute “the extreme edge of experience”? The only answer I can find in Manguso’s essay is that motherhood requires self-effacement, perhaps total. “The point of having a child is to be rent asunder, torn in two,” she writes. “It is a shattering, a disintegration of the self, after which the original form is quite gone. Still, it is a breakage that we are, as a species if not as individuals, meant to survive.”

Men appear in Very Cold People as fathers, uncles, brothers, teachers, classmates, doctors, and police officers, but their actions are largely suspect, regardless of their roles:

We’d been told that Officer Hill was an odd person. Sensitive. We thought that the tennis coach was odd, the volleyball coach was odd, Bee’s father was odd, Amber’s brother was a little odd…

Ruth’s father, an accountant, makes far fewer appearances than her mother, though he is no less perplexing and harmful. A scornful shadow, he screams, crows, sneers, and rages at Ruth. The best he can muster is dropping her at school forty minutes early before zipping away in his used roadster. Manguso doesn’t let men off the hook for their actions—which include sexual abuse—but that reckoning isn’t a major part of the novel. Her focus is the way mothers allow shame to perpetuate.

The argument Manguso seems to be making is that if Ruth can’t receive love, it’s because it hasn’t been given to her by the person most capable of doing so, her mother. Ruth internalizes each new humiliation her mother doles out; she calls that shame “my birthright.” This argument extends to the book’s other mothers, including those of Amber, Bee, and Charlie, with the negligence stretching back generationally. Ruth learns that her “mother’s mother hadn’t wanted to hold her babies and was sent to a home to get better, and that when she came back, she was never the same.” Her aunt Rose tells Ruth that Roger, Rose’s husband, was separated from his parents as a child when he was sent to a sanatorium to recover from scarlet fever. These tales of familial fragmentation send Ruth into a panic. “I thought of all the questions I wanted to ask Aunt Rose,” she thinks. “What had happened to my grandmother? To Roger? To my mother? And what would happen to me?”

Ruth tells herself that her mother’s lack of care for her is meant as a form of protection. When she pretends to forget the color of Ruth’s eyes or ridicules the way her mouth looks with braces, Ruth reasons that “it was only because my mother’s love was so much greater than all the other loves. It was that much more dangerous, so she had to love me in secret, absolutely unobserved by anyone, especially me.” But this talismanic love doesn’t suffice to ward off danger, for Ruth or any girl.

In a recent essay on trauma’s “totalizing identity” in contemporary culture, Parul Sehgal writes, “Trauma trumps all other identities, evacuates personality, remakes it in its own image.”2 Sehgal is describing Hanya Yanagihara’s novel A Little Life (2015), but the sentence could also characterize the last stretch of Very Cold People. Amber, Bee, and Charlie are all victims of sexual abuse, and as the predations intensify, Manguso expels each girl from the narrative, one by one; they move, they die, they disappear.

I won’t divulge the details, to avoid giving away too much of the plot—and in any case the specifics turn out not to matter so much. She casts not just Ruth’s friends in the traumatic role but all of the town’s girls and women, and the earlier collective of friendship pins and strawberry lip gloss becomes an indiscriminate legion of abuse survivors, voiced no longer in the first person but in the third:

All of these Waitsfield girls together, with their burdens. Imagine twenty of them in a room, all day, thinking about each other. Thinking about what was still going to happen to them. They could see the future, a little. They so nobly faced it, patiently waiting.

Every girl becomes a victim, as if it were unavoidable, and they grow up to be mothers who are complicit in the perpetuation of that trauma, partly through their silence:

All the girls in town thought they were unusual, that they were the only ones, the only weird, unlucky little ones. Some of them died of that bad luck, that terminal uniqueness. Some of them got pregnant and had babies and stopped being girls. And after that happened, those mothers took up the story they had been told, the big lie that had almost done them in, dusted it off and told it to their sons and daughters as if their lives depended on it. That was just one time. It won’t happen to you.

Ruth comes to regard her own mother’s unspoken experience of abuse as normal, not rare: “It was too common even to register as a story. It wasn’t even a story at all.”

Manguso’s evocation of this assemblage of women suggests a desire to share pain, to recognize one another’s suffering, and perhaps to find a way out, but by couching it in a tradition of lies that extends on and on, without resolution or relief, the trauma seems to erase any distinction between individuals and forgoes any recognition of distinct inner lives, to say nothing of afterlives. Claims of uniqueness are often used to help conceal and perpetuate sexual abuse; relegating girls and women to an indistinct mass can be equally damaging. Manguso illustrates this paradox, but she does so at the expense of her characters, who are dispensed with when they no longer serve a purpose and replaced by an anonymous group of “all the Waitsfield girls.”

The very forms of Manguso’s books—fragmentary, aphoristic, discrete, or however one chooses to characterize them—resist clear narrative paths, and in doing so they can invite new possibilities. However, for Ruth, whose future we just glimpse at novel’s end, there is only a hint of what it means to live beyond the damage of her childhood, and Very Cold People stagnates—a story of trauma that does not move beyond its own crisis. I thought of all the “apparent nothing” between memorable moments that Manguso found missing from her diaries. So much of childhood and adolescence is lived in that insignificant time, waiting to be able to make one’s own decisions. Throughout the novel, Ruth is waiting to be in charge of her own life. She is waiting, as Manguso writes of all the Waitsfield girls, for her future to begin.