In 496 CE a giraffe arrived at Constantinople. It was a rare event. The exotic animal was brought by ambassadors from the distant south, possibly from Nubia (a kingdom on the Nile roughly coextensive with modern Sudan). It had lingered on its way at Gaza (then, in more fortunate times, a rich entrepôt between the Red Sea and the Mediterranean), where it impressed a professor of Greek literature. It may also have left its mark on local craftsmen. Mosaics laid down at this time in a synagogue and a church not far from Gaza show realistic giraffes with small horns, steeply sloping backs, majestic necks, and spotted hides, when most other mosaics of giraffes showed them looking like camels with measles.1

In Constantinople, the giraffe would have been placed in the menagerie attached to the imperial palace. On ceremonial occasions—the Byzantine equivalent of photo ops—the emperor would descend from the palace to feed the giraffe with his own hands. By doing this, he showed that the strange animal had been tamed by his presence. The nations that ringed Byzantium along the edges of the known world were supposed to behave like that biddable beast and succumb to the charms of the empire.

It was a very “Byzantine” view of the world. All roads were thought to lead to Constantinople. All good things—high thought, high art, stable rule, and the comforts of civilized living—if found elsewhere were assumed to have come from that single creative center, as if fed from the hands of the emperor.

“Africa and Byzantium” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art has been put together, and its objects commented upon at length, largely in order to rebut that narrow, de haut en bas view of the relationship between Byzantium and the wider world. This splendid exhibition was gotten underway by Helen C. Evans, who for many decades has stunned the public with exhibitions of the art of Byzantium and its relations with its immediate neighbors in the Islamic and the Slavonic worlds.2 The catalog, skillfully edited by the exhibition’s curator, Andrea Myers Achi, reaches even farther: across the Mediterranean shore of Africa, from the Atlantic to the Red Sea, and from Gaza to the sources of the Nile.

The exhibition was organized under extraordinary conditions of epidemic and war only too reminiscent, to historians of the period, of the afflictions that fell on Byzantium even at the height of its power under the emperor Justinian in the mid-sixth century. For this reason, its richness is all the more astonishing. Masterpieces that we had long resigned ourselves to seeing only in the pages of art history books or in archaeological reports are here in their full opulence: for example, the majestic Coptic tapestry of the Virgin Mary from the Cleveland Museum of Art and the vivid encaustic icon of Mary, Jesus, and two saints (one of the very first of its kind) from Saint Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai.

Small objects long known to experts are also present, such as the mosaic covering of the tomb of a farmer from the region of Carthage in the age of Saint Augustine, with the proud inscription: “A pious man, Dion, [rests] in peace. He lived for eighty years. He planted four thousand [olive] trees.” We can now see (as we never could see in books) the few gold leaf cubes in Dion’s modest mosaic twinkling, a long way from Carthage, in the light of the Met. All this material is arranged in a series of spacious galleries, each of which is filled with the riches of a particular region.

The aim of the exhibition is to give voice and density to the cultures with which Byzantium interacted over the many centuries of late antiquity and the Middle Ages. This interaction took many forms. In every case, what we learn is a new respect for the African side of the dialogue between Byzantium and the wider world.

We are dealing with four Africas. From west to east, the first of these is what the Romans called “Africa.” This was not the continent, only the western end of its Mediterranean coast, which roughly coincides with modern Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco. Then comes Egypt. These two provinces were the richest in the entire Roman Empire. Ever since the conversion of the emperor Constantine in 312, they had been officially Christian. Roman Africa, for the Latin world, and Egypt, for the Greek East, were intellectual powerhouses—the one produced Augustine of Hippo, the other a succession of combative theologians, such as Athanasius and Cyril of Alexandria, and leaders of the monastic movement such as Anthony. By contrast, Nubia and Ethiopia were independent, distant kingdoms.

The rise of Islam changed this map. By the end of the Middle Ages, Christians had disappeared from Roman Africa and had become—and still remain—a minority in Egypt. Nubia held out as a Christian kingdom until it was conquered by the Ottomans in the sixteenth century, while Ethiopia has retained a Christian identity despite the great diversity of its population.

Advertisement

Each region developed a culture of its own. Take, for example, Nubia, the possible source of that giraffe. Directly south of Egypt, it offers at first sight an unforgiving landscape of high sand dunes piled up against dreamlike miniature pyramids—ghosts of the ancient kingdom of Meroë, which thrived from 270 BCE to 350 CE north of Khartoum. Yet recent archaeological discoveries and the interpretation of excavated documents have revealed a society of unexpected sophistication. A bridal casket from Qustul, lovingly put together with intricate ivory ornamentation set in precious wood, catches the eye at the end of one of the galleries. This opulent object had been unhesitatingly ascribed by art historians to the workshops of Alexandria, for in their opinion only a center such as Alexandria was thought to be capable of producing such a superior work of art. It has now been shown to have been a local product.

Patient new work on documents discovered in the ruins of impressive Christian churches, such as Faras and Qasr Ibrim, has shown that throughout the Middle Ages Nubia had a monetary economy and a legal system on a level with that of Egypt and the Mediterranean. It was a remarkably long-lived kingdom. The frescoes of the church at Faras showed Nubian kings, officials, and bishops held in the arms of great protecting figures that date from the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries—the days of Henry V and Joan of Arc. Only with the Ottoman conquest did Nubia become part of the Islamic world, and its churches sank beneath the desert sands. But even today, the impressive ruins of the monastery of Deir Simeon, on a ridge above modern Aswan—a medieval building as enormous as any Romanesque monastery in Europe—still stand as a reminder that a Christian, not an Islamic, power once controlled the middle Nile.

And where did the elites of such a kingdom look in order to find the center of their world? Not necessarily to Byzantium, though they might occasionally visit it. At the time of the siege and sack of Constantinople by Western crusaders in 1204, Robert de Clari, a knight from Picardy in France, met a king of Nubia in the city. A man of royal bearing with a cross branded on his forehead, he told Clari that he was only passing through. He wished to travel west, to visit the Latin shrine of Saint James at Compostela. But he hoped to return so as to end his life in the Holy Places in Jerusalem, as befitted a Christian prince. Jerusalem—not Constantinople, not Rome—was regarded as the brightest, the most intensely active nebula in the widespread galaxy of Christian churches that stretched across Africa and the Middle East.

How did the varied points in this galaxy connect with each other? The exhibition catalog has a vivid map of the travel routes of the Roman Empire in late antiquity, and we are frequently told that there was a high degree of interconnectivity between Mediterranean Africa and the Middle East. But we are dealing with a world where no one (except a high-ranking courier) could cover more than twenty to twenty-five miles a day (and camels were little better than horses, except that they could carry heavier loads with less need for water). In such a world “interconnectivity” meant something rather different from what it does today.

If there was what the historian François-Xavier Fauvelle has called “a distinctive way of being global” in medieval Africa,3 it was not our modern way. One form of exchange, however, came close to being global. Many of the objects on display in the exhibition once circulated widely as part of a flow of what have been called “charismatic” goods.4

Charismatic goods were privileged goods. They bore with them a charge of life-enhancing energy, delight, and majesty that appeared to have been brought from the ends of the earth. They were supposed to transform their owners, touching them with a speck of glory that raised them above the humdrum routines of daily life and the ordinary exchange of goods. Like the giraffe sent to the emperor, their very strangeness made the possessor himself—and those around him—seem strange and somehow more exalted. Not all of them were religious: jewels and rich textiles were just as important as relics and icons, and they too were surrounded by a similar numinous aura. Such goods were the delight of the elites and were considered to be indispensable adjuncts to the courts of kings. Ambitious rulers were expected to reach out with passion—almost with a craving—to distant lands in order to possess them.

Advertisement

And few African rulers were more ambitious than the negus—the king—of Ethiopia. In 1402 King Dawit II sent representatives to Western Europe for the first time in the history of his kingdom. His ambassadors returned from Venice loaded with Italian brocades:

And when the king with his priests and the chiefs of his army looked at all this collection of garments and adornments, of various colours, they admired them greatly. And then the king told those who were standing before him: have you seen garments like this with your eyes or heard with your ears from your fathers till now? And they answered him…No, we haven’t seen it, and we haven’t heard with our ears of a thing like this. Because they do not seem to have been woven with a hand of earthly creatures, but with that of heavenly creatures.

These were truly charismatic gifts, brought from a distant land and touched with a sense of the supernatural.

This colorful moment of outreach to the West has been skillfully analyzed by Verena Krebs in her challenging book Medieval Ethiopian Kingship, Craft, and Diplomacy with Latin Europe.5 She sets this encounter, which has usually been seen through Western eyes, against its Ethiopian background. She shows that the arrival of such goods was not perceived as a handout from a superior West to an underdeveloped Ethiopia. Far from it: these gifts of precious artifacts validated the claim of a Christian monarch such as Dawit II to draw to himself the charged wonders of distant lands.

But the circulation of charismatic goods was by no means limited to such grand occasions. Many of the artifacts that make up the Ethiopian section of the exhibition were seen as charismatic objects. Brightly colored icons in a variety of styles, great Gospel books laboriously copied onto heavy parchment, and exquisitely fretted crosses: all these circulated as holy things before they ended up in the cool, hygienic showcases of modern museums. We must try to recapture something of the thrill of their first appearance and use in crowded churches, remote monasteries, and pious households.

A belief in their charged quality resolved a dilemma in the Christian imagination shared by all the churches of Africa and the Middle East: how to make present in one’s own region the blessing associated with objects that drew their power from having come from a great distance. Ethiopians had few illusions about the distances that separated them from Jerusalem, the imagined center of the world. But they were determined to overcome them. Like the much-traveled Nubian king whom Robert de Clari met in Constantinople in 1204, Ethiopian pilgrims flocked to Jerusalem and the Holy Land in the late Middle Ages, as they still do today. It was also in Jerusalem that Western pilgrims first encountered representatives of a Christianity very different from their own, as the Ethiopians danced all night to the beat on the ground of their long iron crosses in front of the chapel of the Virgin at Golgotha.

But what of those who never made this journey, or who did and then returned to their mountain homeland, so very different from the bustling Holy Land? There is a poignant detail in the story of an Ethiopian saint in which a pious pilgrim to Jerusalem was reassured by a local holy man that the waters of the Tekezé (a river that flows through Ethiopia and eventually joins the Nile) were as sweet as the waters of the Jordan.

Here a central paradox in the Christian imagination came into play. Christianity was a universal religion: God and the saints were everywhere; and yet God could also be anywhere at any moment and anywhere believers might find themselves confronted with the fullness of His presence and (more often) with that of His angels and saints. There was only one distance that mattered: the distance that human sin had placed like a veil between heaven and earth.

And there were places where, for privileged individuals, that veil was lifted. We need only enter the church of the great Red Monastery beside the Nile at Sohag in Upper Egypt to be dazzled by the sheer late-classical exuberance of the sixth-century frescoes. The colors (newly restored by a team guided by the art historian Elizabeth Bolman) scorch the eye.6 For a moment the veil is lifted. We are in heaven.

Farther down the Nile, in Ethiopia, remarkable human creativity was summed up in legends that present artistic breakthroughs as based on similar glimpses of the other world. In the sixth century Saint Yared, the reputed inventor of the distinctive Ethiopic liturgical chant (much as the “invention” of plainchant was ascribed to Pope Gregory the Great), was believed to have been taken up to heaven. There he heard the chant of the seraphim around the throne of God, which he then reproduced and passed on, just as he had heard it, to his disciples, the cathedral clergy of Axum. So exciting was this new sound that the negus, Gabra Masqal, was said to have driven his great iron cross (there is a splendid Nubian example in the exhibition) into Yared’s foot as he beat time to the music.

This view saw the human race as surrounded by an entire universe of benign “presences” separated from it not by distance but by the veil of sin. Often, it was believed, these presences made themselves accessible, as if through a chink in the veil. We should bear this in mind when we look at the particularly colorful collection of Ethiopian icons of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Many of these are robustly indigenous and have been very influential in forming our modern taste for Ethiopian art. But others plainly show the influence of Italian paintings. Art historians and purchasers of Ethiopian art tend to look down on these icons as inauthentic, clumsy knockoffs of superior European models.

Maybe, at the time, Ethiopians did not see these works that way. What mattered for them was the imagined presence of the Virgin herself waiting quietly behind the bright veil of paint. There was nothing inauthentic about that real presence. If that was so, why should she not be shown swathed in charismatic goods, wearing a Gothic crown and dressed in the same rich Italian brocades that had delighted King Dawit and his court?

This sense of timeless presences also explains the display of “magical” scrolls at the end of the exhibition. These scrolls have done much to foster the impression of Ethiopia as a somewhat spooky generator of “primitive” art. They are no such thing. They are detailed maps of an unseen world. They reveal an entire invisible counterkingdom of malevolent presences held in check (and only just) by regiments of angels and by a powerful company of saints.

Such scrolls were by no means restricted to Ethiopian Christians. The worldview behind them was taken for granted by Christians, Jews, and Muslims. Long lists of spells are the advice columns of the hopes and fears of believers of all faiths throughout Africa and the Middle East. In Coptic Egypt, one petitioner is told “how to acquire a beautiful singing voice.” Other spells promise to charm the hearts of judges or to ensure that a loss of memory—a senior moment—falls on one’s opponent in the middle of his speech. Identical spells can be found in the papyri of Greco-Roman Egypt. They take us back to the noisy courtrooms of ancient Rome. In the great books of magic, the ancient world never died.

Muslim rulers gloried in such scrolls. In 1445 Sultan Badlay, the ruler of a kingdom in the Horn of Africa adjacent to Ethiopia, went into battle against the negus Zar’a Ya’eqob with scrolls twelve, ten, and eight cubits long wrapped around him. It did him no good. He was struck down by the javelin of Zar’a Ya’eqob himself, who claimed to rely only on the protection of the Virgin. Yet not even the power of the Virgin was considered quite enough. The clergy of the palace kept a book of secret names “so huge and heavy that two men would not be able to carry it on a journey,” to recite in times of plague or during the terrifying thunderstorms of upland Ethiopia.

Of all the precious goods accumulated by the rulers and ecclesiastics of late medieval Ethiopia, the most charged of all were books. This is something of a paradox. Literacy does not seem to have been widespread in medieval Ethiopia. The costs of production were horrendous by modern standards. It took fifteen months at least to copy an entire Bible, and when copied, the weight of such a huge gathering of parchment virtually immobilized it, confining books to a narrow radius around the court and to a few flagship monasteries.

But books were crucial. Along with the Bible, some books (usually translated from Greek, Coptic, and Arabic) were thought to keep Ethiopia in touch with the lifeline of Christian truth. This lifeline did not only extend back to the world of the Gospels. Books also preserved the memory of the great controversies that had shaken the schools of Alexandria and Antioch, Rome and Constantinople in the fourth and fifth centuries. They were handed down from generation to generation and from translator to translator. They brought the exotic scent of the late antique Mediterranean to monasteries perched on mesas high above the Rift Valley.

This was the past to which many outstanding Ethiopian men and women held with remarkable tenacity. To abandon it, or even to seem to abandon it, was to unhook the life support system of a Christian country. Such a backward-looking view might seem to be a recipe for a mindless conservatism. But this was not the case. Throughout the late Middle Ages and the early modern period, Ethiopia was regularly agitated and invigorated by controversies on the exact meaning of those books and how they applied to the life of the Christians of Ethiopia. Why was this so?

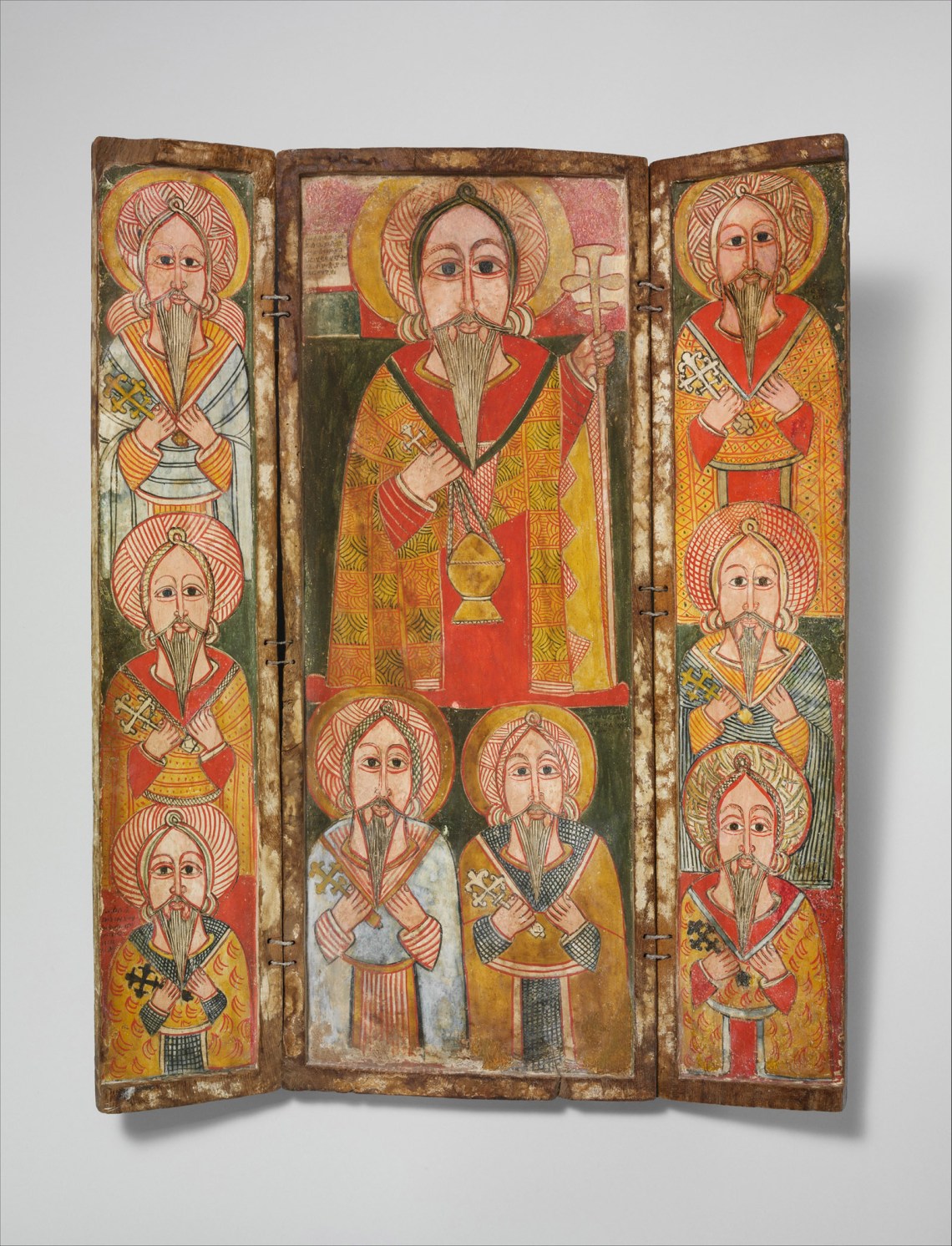

We should never forget the distinctive nature of Ethiopian monasticism. The great monasteries were the think tanks of the realm. Like think tanks, they often gloried in controversial statements and disagreeable conclusions. And there was no higher authority—no pope, no strong bishops (as in the medieval Catholic church), not even the negus—to keep them together. They were often led by respected figures whose “children” would spread across the land in near-autonomous networks as strong as (but more independent than) the religious orders of the West. At the Met we can see portraits of these figures, such as that of Eustathios with his disciples (see illustration on page 23). His piercing eyes, long beard, and large, tightly bound turban reveal a man of spiritual power untrammeled by any other authority.

One of the most courageous of these monastic leaders, Estifanos (Stephen) of Gwendagwende, put his finger on the problem: “There are books in our country…but there is no court of appeal.” The result of this situation was clear to Estifanos’s principal opponent, none other than the negus Zar’a Ya’eqob: “If the books had sticks they would fight each other.”

Estifanos himself was no mean fighter. He refused to change his mind on the issue of keeping the Sabbath both on Saturday and on Sunday, thereby “nailing together” the observances of both the Old and the New Testament. He was even accused of saying that Christians should not prostrate themselves to the king or even to images of the Virgin Mary, but only to God. As a result, he was brutalized by the negus and his courtiers: “The breadth of his cheeks and the level of his lips became equal to the tip of his nose, because of his swelling from the beating.”

One seldom reads such a minute description of physical violence in a medieval text. Yet when we look at the icon of Abba Estifanos, painted in vibrant colors that did justice to his glory, what we see is not the beaten monk but a figure of spiritual power clasping the instruments of his authority: a great cross of interwoven gold and a book. Kings, courtiers, and bishops: he would outlive them all as a guardian of the truth.

In one of his many wise and rousing lectures delivered just after the war, in 1945, the great Byzantinist Norman Baynes summed up the interest that the study of Byzantium might still have for modern persons: “The defence of a way of life. Yes, really that essay must be written. It would even have its relevance for us today.”7 The Ethiopians and many like them across Africa were also defending a way of life. And they did it their way.

This Issue

February 8, 2024

Who’s Canceling Whom?

The Bernstein Enigma

Ethical Espionage

-

1

See Pierre-Louis Gatier, “Des girafes pour l’empereur,” Topoi, Vol. 6, No. 2 (1996); and Diklah Zohar, “A New Approach to the Problem of Pattern Books in Early Byzantine Mosaics: The Depiction of the Giraffe in the Near East as a Case Study,” Eastern Christian Art, Vol. 5 (2008). ↩

-

2

See the catalogs of these exhibitions: The Glory of Byzantium: Art and Culture of the Middle Byzantine Era, AD 843–1261 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1997); Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261–1557) (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004); Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012); and Armenia: Art, Religion, and Trade in the Middle Ages (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018). ↩

-

3

François-Xavier Fauvelle, The Golden Rhinoceros: Histories of the African Middle Ages (Princeton University Press, 2018), p. 11. ↩

-

4

See my “‘Charismatic’ Goods: Commerce, Diplomacy, and Cultural Contacts Along the Silk Road in Late Antiquity,” in Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity: Rome, China, Iran, and the Steppe, ca. 250–750, edited by Nicola di Cosmo and Michael Maas (Cambridge University Press, 2018). ↩

-

5

Palgrave Macmillan, 2021; see my review in these pages, October 7, 2021. ↩

-

6

The Red Monastery Church: Beauty and Asceticism in Upper Egypt, edited by Elizabeth S. Bolman (Yale University Press, 2016). ↩

-

7

“The Hellenistic Civilization and East Rome,” in Byzantine Studies and Other Essays (London: University of London, Athlone Press, 1960), p. 23. ↩