“I have built a monument more lasting than bronze.”

—Horace

In 1943, as the war with Germany raged on, Joseph Stalin decided to boost the Soviet people’s morale by gifting them an anthem. “The Internationale,” a de facto anthem since October 1917, had been written by foreigners and called for world revolution, an outdated message given Stalin’s need for the Western Allies’ help to defeat Hitler, and for bolstering nationalistic sentiment at home. An anthem competition was thus decreed, and nearly 200 Soviet composers and poets were asked for submissions. Among them was thirty-six-year-old Dmitri Shostakovich.

Stalin had judged Shostakovich’s music once before, and things had not gone well for the composer. Shortly after Stalin’s appearance at Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District in 1936 in the Bolshoi Theater, during which the “Father of Nations” was visibly dissatisfied, an unsigned Pravda editorial titled “Muddle Instead of Music” had accused the composer of reveling in chaos and cacophony, pandering to formalist “petit-bourgeois ‘innovations’” instead of interests of the people, and attempting “to create originality through cheap clowning.” A campaign against formalism in art had followed, causing Shostakovich to withdraw his already composed Fourth Symphony. The decision may have saved his life.

Nearly two harrowing years of “The Great Terror” later, during which many of his colleagues, relatives, and friends arrested or executed, including his patron, Marshal Tukhachevsky, Shostakovich had been restored to favor as the composer of the triumphant Fifth Symphony, which managed at once to appease his detractors at home and advance his worldwide fame as one of the century’s leading composers. By the time of the anthem competition, Shostakovich had scored another success with his wartime Seventh Symphony dedicated to the siege of Leningrad, his native town. Though back at the pinnacle of Soviet culture, he knew he could be cast down at any time.

Despite making it to the finals, none of Shostakovich’s anthem entries won, judged by Stalin as “too complex” and “excessively romantic.” The winning composition, a spruced-up “Song of the Bolshevik Party” presented by the founder of the Red Army Choir, may have lacked Shostakovich’s originality, but it had all the major chords and fortes Stalin wanted. From 1944 onward, “An Unbreakable Union,” sung by the all-male choir with powerful brass and percussion, was played at countless official ceremonies, school meetings, and sports competitions. It also functioned as a communal alarm clock: broadcast every morning at 6 AM on the Mayak Radio, the anthem’s powerful opening chord jolted millions of Soviet citizens out of sleep.

If losing the anthem competition disappointed Shostakovich, he made no mention of it in his letters, and consigned the score to his desk drawer. After Stalin’s death in 1953, the composer’s career was more secure. He wrote at a vigorous pace and in 1960 was tapped to become the general secretary of the Union of Composers. There was a caveat: he had to join the Communist Party. The composer’s friend Isaak Glikman recounted an episode that took place in the apartment of his sister before Shostakovich’s final induction in June of that year: amid violent sobs, the laureate of five Stalin’s State Prizes, two Orders of Lenin, the Order of the Red Banner of Labor, and People’s Artist of the USSR lamented being “hounded” and forced to join the “Party of violence.” He joined anyway, then poured out his torment in the String Quartet No. 8 (Opus 110), composed in July and officially dedicated “to the victims of fascism and war.” The composer told friends he intended the quartet to be his epitaph.

In public, Shostakovich soldiered on. His highly visible position in the Composers’ Union meant that he had to handle all kinds of musical matters associated with “socialist construction.” One request, dated May 12, 1960, came from officials of the Black Sea port of Novorossiysk. To honor the anniversary of their city’s liberation from the Germans on September 16, 1943, they wanted to add sound to the Flame of Eternal Glory monument at Heroes’ Square, right by the harbor. Could the Composers’ Union help with arranging appropriate fragments from the works by Russian composers—not longer than two minutes, mournful at first, solemn in the middle, and galvanizing in the end? A local radio enthusiast had already engineered a clock-operated playback mechanism, to be built into the monument’s granite foundation.

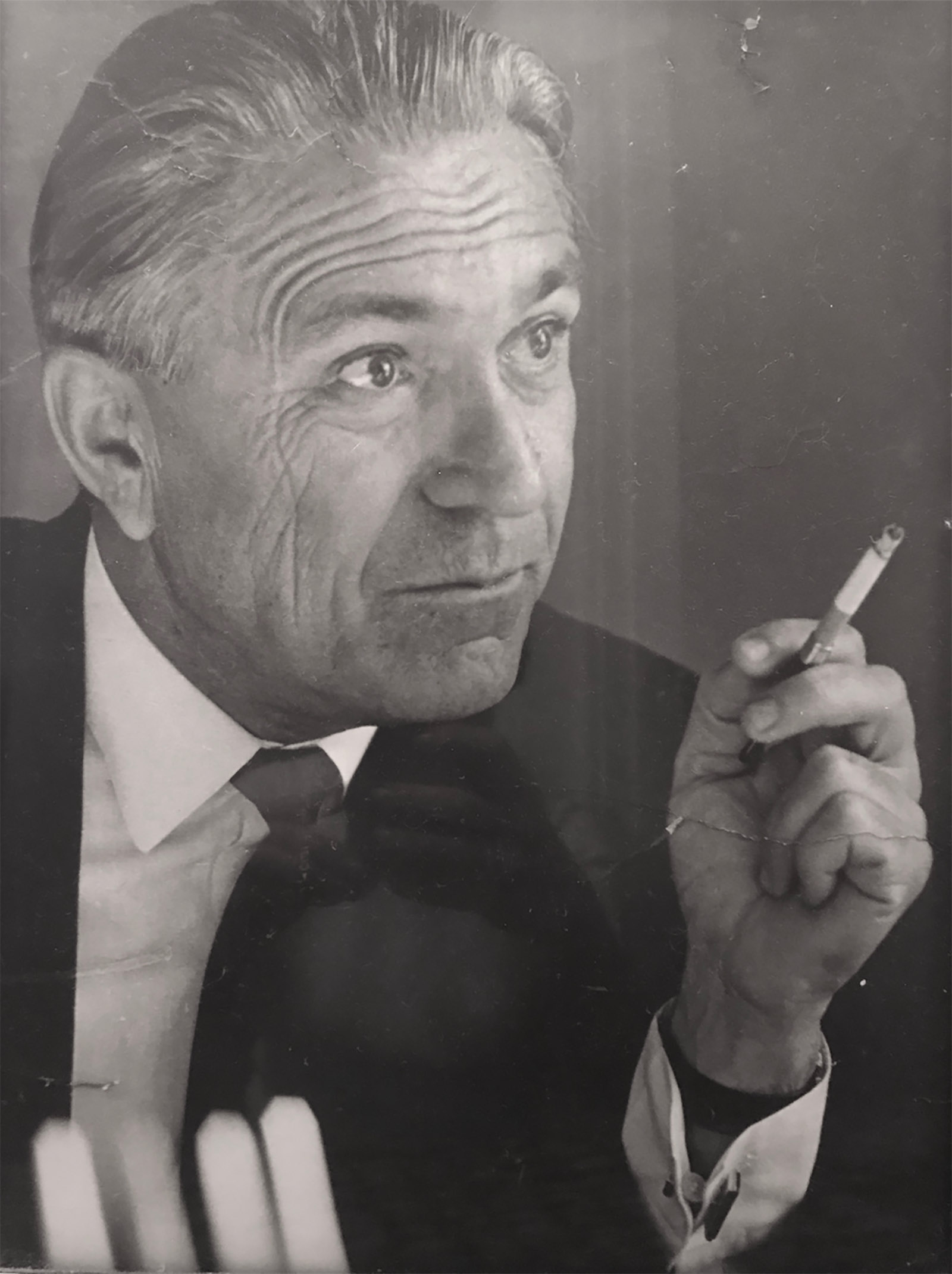

The petition was signed by Anatoly Alexandrov, second secretary of Novorossiysk’s Communist Party Executive Committee, a Soviet equivalent of vice mayor. This official, known as “the Musician” among Novorossiysk’s leadership for his affinity for all things musical, including the very practical skill of playing popular song at parties, was my grandfather.

Advertisement

Unlike Shostakovich, my grandfather had had no qualms about joining the Party. He did that back in the 1930s, at the agricultural equipment plant Rostselmash in Rostov-on-Don, where he’d enrolled straight after school, compensating, in part, for his non-proletarian origin (he came from a merchant’s family). Like Shostakovich, who was seven years older than he was, my grandfather was deeply affected by music at an early age, playing anything and everything on the piano that his father had acquired in a trade for a sack of flour during the hungry post-Civil War years. Endowed with perfect pitch and remarkable dexterity, he was advised by his teachers to go to Moscow. But the year was 1929, and the country, hurtling toward industrialization, needed other talents.

Luckily, in addition to “Stalinets” tractors, Rostselmash also had amateur music circles, part of “art to the masses” movement, and so did the Rostov Railway Management that eventually recruited my grandfather. He played in these ensembles as he rose up the Party ladder. He also played at social events and silent-movie theaters, as well as in amateur competitions. His wife, my grandmother, was an avid accordion player, so the two were the life and soul of many parties. In 1940, Grandfather was invited to play Tchaikovsky’s technically challenging Piano Concerto No. 1 with the Rostov Philharmonic. His performance of the Grieg Piano Concerto, accompanied by an orchestra consisting exclusively of amateur railroad musicians, was broadcast through Comintern Radio, the USSR’s first radio station named after the Communist International.

Then, in 1941, Hitler broke the Nazi–Soviet pact that had kept the USSR out of the war for nearly two years, and German forces advanced rapidly into Russian territory. Comrade Alexandrov spent the war managing military transportation for the strategic North Caucasian Railroad. At the end of the war, he brought back from Berlin two accordions and a black Seiler concert piano. In 1956, with a degree in railroad engineering earned part-time, he took an appointment as head of Novorossiysk Railway Station, which had recently been badly damaged by a collision of two oil-tanker trains. He restored the station in eleven months and was promoted to join the Novorossiysk Executive Committee of the Communist Party as a secretary for industrial development. In addition to his direct duties, he sponsored construction of Novorossiysk’s first permanent theater. Famous orchestras could then visit the city as they toured.

Writing his “musical monument” request to the Union of Composers in May 1960, my grandfather, at that point nearing the peak of his Party career, addressed it specifically to Shostakovich, whose work he had been following since the 1930s, and whose public pillorying after Lady Macbeth had distressed him. A man who privately hated Stalin with passion, my grandfather was deeply impressed by Shostakovich’s “Leningrad Symphony.” Though officially branded as anti-fascist, it was described by the composer himself as the “music about terror, slavery and bondage of the spirit.” My grandfather, who had himself spent nine months in prison on false charges, understood exactly what Shostakovich’s music was about.

The reply from the Union, signed by Shostakovich himself, came quickly. “Comrade Alexandrov: we have received your request and are currently selecting musical fragments, which would then be recorded on magnetic tape and sent to you promptly.”

But weeks and months passed with no word from Moscow. Concerned about the deadline, my grandfather sent another letter on August 18 and received a call from a Union official named Samuel Urbach. The Union’s musicians, he said, were unable to find the fragments that would meet the “mournful—solemn—galvanizing” criteria of Novorossiysk comrades, let alone fit them into the requested “under two minutes” length. For that reason, Urbach continued, after a dramatic pause, Dmitri Dmitriyevich was promising to compose the music himself, as a gift to the city. He was worried, though, about the September 16 deadline. My grandfather, thrilled, told Urbach they would move the opening ceremony to accommodate Shostakovich’s schedule.

The recording and the original orchestral score, titled “Novorossiysk Chimes” (Opus 111b), arrived on September 17. But when the city officials gathered in front of the tape recorder, bizarre dance music spewed at them from the loudspeakers. As they lamented the inaccessibility of modern art, someone guessed that they needed to compare the recording’s speed with the speed of their apparatus; the two didn’t match. So they raced to the city’s only broadcasting station. In the anxious silence of the studio, the celesta’s crystalline introduction, soft yet clear, sounded for the first time. “There and then,” wrote my grandfather in his memoir of the episode, the only one of his eventful life he chose to commit to paper, “I knew that I was listening to something that would touch the hearts and souls of millions.”

Advertisement

He was right. When, on September 27, Peace Day No. 2 (the USSR never lacked commemorative dates), the Novorossiysk Chimes began playing for the first time at the city’s Heroes’ Square at 6 PM, the crowds surrounding the Flame of Eternal Glory—a six-foot-tall bronze torch framed by granite columns—fell silent. They stayed silent for the duration of the piece, a transformation of tragedy into triumph, extraordinary in its brevity and completeness. When the last notes drifted above the monument’s flames, pale in the lingering daylight, people stayed at the square another hour to hear the piece again. Many were weeping.

This was not surprising. Like Shostakovich’s native Leningrad, Novorossiysk had suffered terribly during the war. The mass of artillery shells, mines, and bombs hurled at the city was calculated at more than a ton for every defender. Even nearly twenty years later, memories of the trauma were still fresh. As the news of the monument’s musical innovation spread through the city, more people came and stayed for hours, the flames slowly reappearing as daylight faded. My grandfather’s voice must have grown hoarse as he greeted the people and recited the story of the Chimes’ creation. At last, everyone left. The music continued to play.

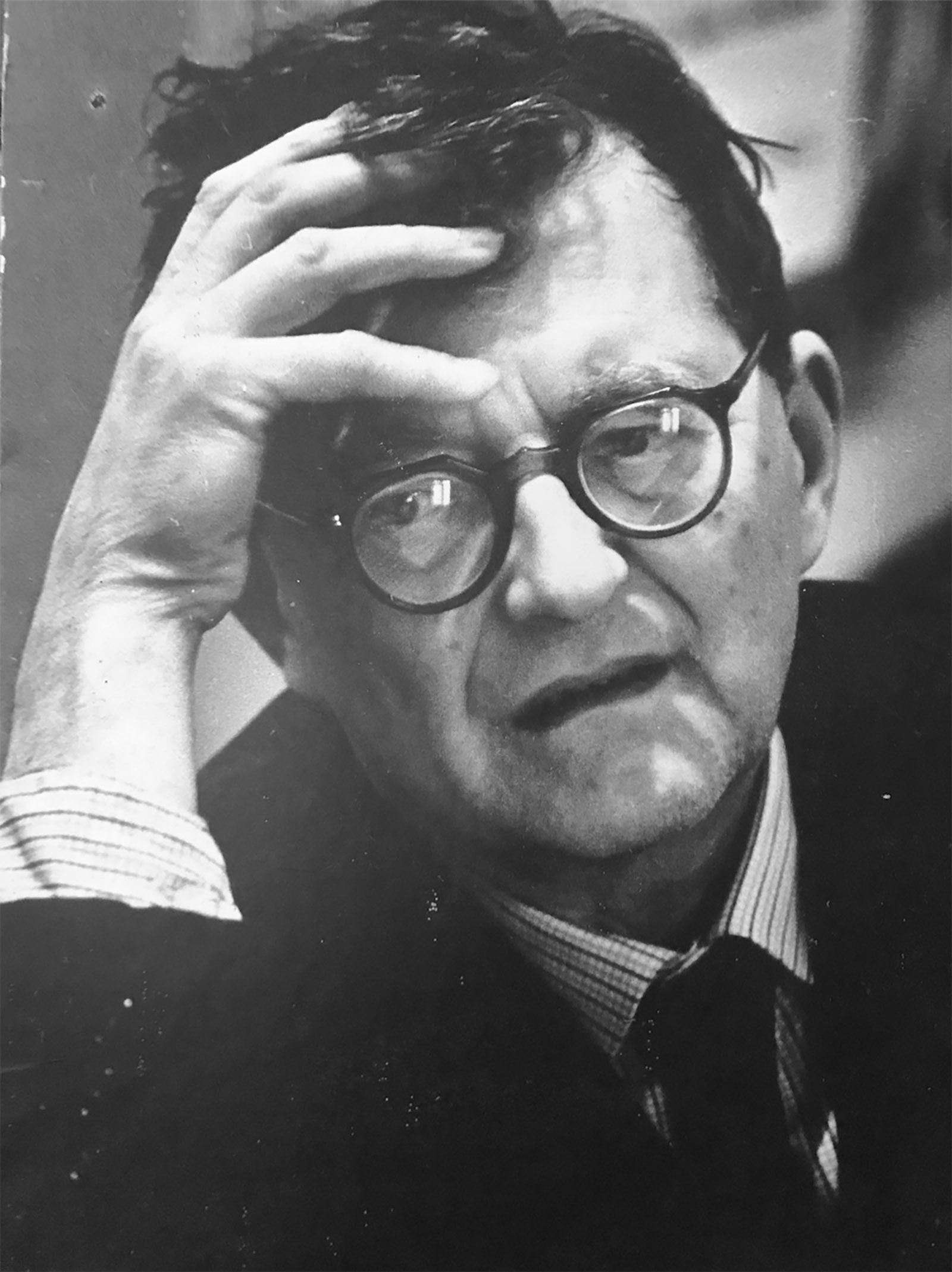

Some six months later, in March 1961, Shostakovich paid a three-day visit to Novorossiysk. My grandfather, by then elected the city’s mayor, was in charge of the composer’s visit. A well-known Izvestiya correspondent and a photographer were dispatched by their Moscow editorial office to cover Shostakovich’s contribution to socialist construction. At the Heroes’ Square, leaning on a cane (Shostakovich had just recovered from a foot fracture), the celebrated composer, now also an Honorable Citizen of Novorossiysk, stood by the granite monument framed by newly planted trees, the sea glittering in the distance, and listened to his music. “This is how I pictured everything,” he told my grandfather.

There was a swirl of the usual welcome activities—visits to the port, the “October” cement factory, the local champagne plant, the city music school, with a special concert by the best students. In the evening, in the overflowing city theater, Shostakovich met with members of the community. Everyone wanted to shake his hand, to wish him “creative successes,” to thank him for his gift to the city. “I haven’t done anything,” he pleaded, with an embarrassed smile.

In his own speech, delivered on behalf of the Union, Shostakovich extolled the human feat of transforming wartime ruins into a beautiful city with seaside promenades, bustling industry, and striking war monuments. Asked about his work, he mentioned the completion of String Quartet No. 8, omitting the “epitaph” designation, and the symphony he was composing at the moment, the Twelfth, dedicated to “the great leader of the proletariat,” Vladimir Lenin.

Later that night, during dinner in his honor at my grandfather’s place across from the city hall, my mother, a ninth-grader at the time, was asked to play one of Shostakovich’s fugues. She bravely did so, received a standard compliment, then came down with a stress-induced fever. For the rest of the company, the evening was pleasant: my grandmother was a wonderful cook, there was no need for speeches, and everything that Shostakovich played generated great excitement. Leaving Novorossiysk, the composer, who had returned to the Heroes’ Square a few more times, promised to remember the city by the sea and the Chimes.

Although the ceremonial part was over, a personal relationship continued. As the new mayor of Novorossiysk, my grandfather had to go to Moscow every now and then. He and Shostakovich would meet up, either at the Hotel Moscow, where my grandfather always stayed, or at Shostakovich’s apartment on Kutuzovsky Prospect. During one of his visits, after a third shot of cognac, my grandfather mustered his courage and started playing the Grieg concerto on a grand piano in Shostakovich’s studio; Shostakovich joined in on an adjacent instrument. Before parting, the composer gave him an autographed box of his Eleventh (“The Year 1905”) Symphony recorded in Paris. It now stands on my piano in California, along with Shostakovich’s portrait by an Izvestiya photographer.

For a man of worldwide fame, Shostakovich was surprisingly approachable. He regularly sent handwritten holiday cards to my grandparents, and when they came to Moscow, procured tickets for them to hard-to-get performances, such as the Moscow première of Britten’s “War Requiem,” which happened to be one of the last performances by Mstislav Rostropovich and Galina Vishnevskaya before they left the USSR in 1974. Once, my grandfather telephoned Shostakovich with the news that he was in Moscow, along with two bottles of Novorossiysk’s famous Abrau-Durso champagne and no less famous, though in narrower circles, some salted bream. “Why are you sitting there all alone?” Shostakovich demanded. “Haul them over!” The composer and the mayor demolished the meltingly oily fish in Shostakovich’s kitchen, the composer’s three family members in attendance, washing it down, blasphemously, with champagne rather than beer, customary with salt fish.

In 1963, my grandfather’s political career came to an abrupt end after he criticized Khrushchev’s policy of industrial enlargement that prompted a local effort to merge three of Novorossiysk’s cement plants into one. As mayor, he took a firm stand against it—and lost his job. A few stressful months later, he became the manager of a timber export venture. He began traveling internationally, and at the age of fifty-two, learned Italian, the language of his main trading partners—and of his favorite opera composers. On the bookshelves in his house, memoirs of famous musicians, which he loved to read on weekends, began to appear in Italian. Soon, newspapers were referring to Anatoly Alexandrov as a “Soviet businessman.” An essay on his career and life was included in a 1973 anthology titled A Soviet Way of Life.

A few years earlier, in February 1967, my mother, then a graduate student at the Krasnodar music college, talked Grandfather into arranging an interview with Dmitri Dmitriyevich during their winter trip to Moscow; she was planning to make Shostakovich’s choral Thirteenth Symphony, known as “Babi Yar,” her diploma work. Shostakovich had composed it in 1962, to Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s poem about the 1941 Nazi massacre of Kiev Jews and in quiet protest against the Soviet government’s refusal to raise a monument for the victims. For those views, Yevtushenko had been denounced by the authorities: the massacre, the party line went, wasn’t specifically anti-Semitic since its victims also included members of other nationalities. Shostakovich was among the few who openly supported Yevtushenko. As a result, even with a censored version of the text, the five-part “Babi Yar” symphony was rarely played. My grandfather, who had followed the controversy through the press, did not object to his daughter’s choice of diploma subject.

They took a local train to Shostakovich’s dacha near Moscow. My mother, eager to meet the composer in her best form, wore only a light jacket and fashionable boots “lined with fish fur,” as my grandfather put it. By the time Shostakovich met them at the path that led from the station to his dacha, she was as cold as the knee-deep snow around them. Shostakovich was alone that weekend; my mother still treasures the memory of her idol frying her eggs and brewing her coffee. When his efforts to warm her up succeeded, she “peppered” him with questions, all of which he answered patiently.

But as far as “Babi Yar” was concerned, Shostakovich advised her against getting involved. “There would be unpleasant surprises at your defense,” he said. “Analyze my Lenin symphony instead.” He and Grandfather then played film-score music four-handed, a homage to their youth, when both earned extra rubles by playing accompaniment to silent movies. While Shostakovich played, the nervous tics that habitually plagued his features disappeared. He seemed almost happy.

Two years later, on another trip to Moscow, my mother met, on Shostakovich’s recommendation, with Marina Sabinina, a renowned Moscow musicologist. Though agreeing that she had talent, Sabinina suggested my mother should start her musicology career by enrolling in another undergraduate program, this time at the Moscow Conservatory’s musical college. My mother, already a piano teacher at the Krasnodar Institute of Culture and a local TV personality, married my father instead.

Though the marriage did not last, it produced me, three years before Shostakovich’s death in 1975. Among my earliest memories were the anguished face staring at me from the black-and-white portrait of Shostakovich above the black Seiler piano that now stood next to my bed, and the sound of Novorossiysk Chimes emanating from the Flame of Eternal Glory as we passed it on our daily trips to the beach with my cousins, who lived right across the way. Serene and precise, the music would drift above the by this time full-grown trees toward the sea, crisscrossed by white ferries. I still hear it now, an ocean away, each time I glance at the two portraits on my piano, one of my grandfather, one of Dmitri Dmitriyevich.

I rarely play that piano: I didn’t inherit my grandfather’s perfect pitch and photographic memory, or my mother’s ability to improvise. What I did gain from Shostakovich’s invisible presence in the cramped khrushchevka apartment in which I grew up was the sense of tantalizing proximity to genius and history and to the men who made it—one with music, another with the monument that enshrined it. Both still awe me.

My grandfather died one year before Gorbachev’s call for “glasnost” (openness) that heralded his perestroika reforms, and six years before the fall of the USSR, when countless monuments came crashing down, now symbols of oppression. But not the one in Novorossiysk’s Heroes’ Square. Though it briefly went silent in the late Nineties, the broadcasting mechanism has since been refurbished and the music continues to drift above the alleys, planted with violets and the park benches on which, long ago, my grandfather sat with me and my cousins. His promise to Shostakovich—“to take care of the Chimes”—remains fulfilled.

My grandfather also died before I could ask him whether he knew that the opening phrases of Novorossiysk Chimes had been composed by Shostakovich in 1943 for the USSR anthem competition. I learned about it, of all places, in adult education school in California, where I taught Russian culture. One of my students, a professional cellist, looked up Opus 111b after I’d played it in class and got a “USSR National Anthem” result. After doing my own digging, I discovered that this was the very competition entry that Shostakovich’s great tormentor, Joseph Stalin, had rejected in 1943. Its leitmotif was, indeed, the familiar opening of the Novorossiysk Chimes.

And so it turns out that time, the final arbiter, is better at picking winners. By the sheer number of broadcasts, playing every hour since 1960, “Novorossiysk Chimes,” now the city anthem, more than measures up to its official national counterpart, with none of the latter’s patriotic bombast. Possibly the most played piece of Shostakovich’s music in the world, the Chimes are also the theme of my childhood, which I carry in the music box of my memory, along with the views of the harbor, the granite monument, and the flames invisible in the bright southern sun—except to those who know they’re there.