Because of the coronavirus, nearly 300 million Americans—roughly 95 percent of the population—are under orders to stay at home. As of last count, sixteen states and one territory have postponed their presidential primaries or switched to mail-in ballots with extended deadlines. The Democratic National Convention has been put off till August, with one official anticipating a “bare minimum” attendance. The possibility of a ghost election in November looms.

Of all political forms, democracy is the most dependent on the participation of its citizens. Critically, that participation is supposed to be collective. Citizens are bound to each other, which makes them a people, and they govern as a people. Democracy “is not an alternative to other principles of associated life,” wrote John Dewey. “It is the idea of community life itself.” And though a voting booth may be more reminiscent of a cubicle or a confessional than an assembly, what we do inside of that booth is a public endeavor.

Yet, if we cannot gather to assemble or vote, much less deliberate, in what sense can we have a democracy? How do we do politics in a pandemic, self-governance under quarantine? Is it possible to supervise the supervisors if we’re too sequestered—or sick—to vote?

*

The question of isolation and democracy has long haunted political writers. It was posed, most poignantly, by Alexis de Tocqueville in Democracy in America—not in the relatively chipper first volume, which was published in 1835, after Tocqueville’s return from the United States, but in the dystopian second volume, which came out in 1840, long after his gaze had settled back on France. In the first volume, Tocqueville could scarcely contain his enthusiasm for the civic mindedness of American democracy, where citizens rushed to build a bridge or take care of some other item of public business. In the second volume, as he contemplated the passage of aristocratic society from the European scene, his view grew darker. Because people in aristocratic societies are linked in time to their ancestral families and homes, he wrote, they “are almost always closely involved with something outside themselves.” Democracy breaks that chain of inheritance. It destroys the familial “woof of time,” leaving “each man… forever thrown back on himself alone.” That isolation, which threatens to “shut up” the self “in the solitude of his own heart,” makes democracy ripe for despotism.

Tyrants, the tradition of political theory teaches us, thrive on the separation of citizens from one another. So isolated are people under despotism, wrote Tacitus, that even the courts conduct their affairs “almost in solitude.” Maximizing space between people clears the public square of all potential opposition and resistance. It is what allows the despot to swing his sword with such abandon. It thus required Tocqueville no great leap of the imagination to think that a nightmarish era of democratic despotism lay ahead. Everything he’d read seemed to compel that conclusion.

Yet the literature of democracy is less settled on this question of isolation than we might think. Some writers have described societies in which citizens are kept apart, or at least away from public life, as not posing any problem for democracy at all. Aristotle, for example, identifies four kinds of democracy. In only one of those democracies do those who are eligible to participate in politics actually take part. Tellingly, it’s the one in which revenues are sufficiently high and widely distributed as to fund the life and leisure of the poor. In that kind of democracy—let’s allow the anachronism of calling it social democracy—the citizens are able to gather and decide their common fate.

In the three other democracies, revenue (or property) is too scarce or unequally distributed to provide anyone but the wealthy with sufficient time and resources to assemble and deliberate about politics. In these democracies—let’s be anachronistic again and call them American democracy—even those of moderate means cannot assemble; they’re too busy working or surviving. Yet Aristotle insists on calling these societies democratic—as do many contemporary defenders of the American system—despite acknowledging their similarity to oligarchies. Citizens may not be physically isolated in these Aristotelian democracies, but neither are they physically isolated in Tocqueville’s democracy. It is the political isolation that counts.

In Federalist 10, James Madison makes the case against those who claim that only small societies can sustain popular government. In such societies, counters Madison, a majority will tyrannize the minority. Larger republics like the United States, by contrast, will take in a “greater variety” of people and interests. Popular majorities, which are rooted in “the possession of different degrees and kinds of property,” will find it difficult in the United States to acquire “a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens.” Even if they do have such a motive, they won’t be able “to discover their own strength and to act in unison with each other.” The greater the number of people who must reach agreement in order to act, the more likely it is that their “communication” will be “checked.” The fragmentation of the citizenry—in other words, their political isolation from each other, their inability to make connections—helps maintain popular government in America.

Advertisement

*

Most writers on democracy, partisans and critics alike, are ambivalent about isolation, seeking to sustain some connections while suppressing others. Rousseau wanted people to rush to the assemblies whenever a public question was posed, but he didn’t want them talking among themselves before they got there. Keeping citizens apart ensured that they would not contaminate each other and find common cause with other people’s one-sided views, that the decision of the assembled citizenry would be in the general interest rather than narrow or partial. Some two centuries later, Betty Friedan’s “problem that has no name” made much of the isolation of the suburban housewife. Yet hundreds of pages into The Feminine Mystique, Friedan allowed that the real problem of the American housewife was “how few places there are in those spacious houses and those sprawling suburbs where [she] can go to be alone.”

During the cold war, defenders of liberal democracy, fearful of the mass politics of fascism and communism, went in the opposite direction of Rousseau. It was better to divide and separate men and women into small groups and associations, directing their attention away from common concerns and the fate of the nation. Such organizations were moderate in their aims, pragmatic in their demands, restrained in their tactics, and deferential to established leaders and traditional institutions. Their members would be made doubly so by their membership. Released from the restraint of these groups, however, men and women would rush into the arms of demagogic leaders, who’d convert this new fund of energy into a mass movement of the right or left—the political valence didn’t matter—seeking total control over the national state. When it came to high politics and the state, it was best for citizens to tend to their gardens, chatting with their neighbors over the fence.

More recently, we’ve seen a version of this cold war argument mounted against populism, in which commentators see in the gathering of large numbers of people a kind of virus threatening liberal democracy itself. It’s not simply the racism or misogyny of Trump’s rallies that makes writers worry; it’s the style of the rallies themselves, which are often compared to rallies on the left, where no such opinions are to be found. “The fervor of Sanders supporters… at his largest events,” The Washington Post reported recently, “are reminiscent of the mega-rallies Trump held four years ago and has continued to stage as he seeks a second term.” What’s worrisome, in other words, is a mass politics in which elites are denounced, opponents are demonized, institutions are challenged, certain forms of pluralism are questioned, and the rabble is roused—the kind of politics and rhetoric that have often marked movements and leaders of the left, such as Lincoln and abolition, that are now thought to be unimpeachable.

So we come back to pandemic politics. For years, many have sought to isolate the contagion of populism. Now we’re seeing the program in action. Bernie Sanders’s campaign—already on life support after the South Carolina primary, then additionally hampered by the quarantine—is now dead. Trump’s rallies have been canceled, at least for now. Yet the end of mass populist rallies has also entailed (Wisconsin aside) the postponement of primaries and elimination of voting booths—the suspension of politics itself, as least as that term is conventionally understood in the United States. Must it be so?

*

There is a counter-tradition, less theoretical than practical, that has seen isolation as neither a threat to, nor an axiom of, democracy. In this counter-tradition, solidarity between citizens cannot be assumed. It must be created—often by men and women with very little of it, under less than promising conditions, in which they are kept politically, if not physically, apart from one another. Let’s call this “inauspicious democracy.” Or simply, democracy.

As Friedan came to realize, the problem of the suburban housewife had little to do with whether she was alone or not. Rather, “she was so ashamed to admit her dissatisfaction that she never knew how many other women shared it.” Women lacked access to any apprehension of what other women were thinking and feeling; they lacked access to other women’s consciousnesses and the means to create a collective consciousness. The reason the problem had no name was that there hadn’t been a conversation that named it.

Advertisement

The first step, then, was to talk. Thus, “on an April morning in 1959,” were a thousand consciousness-raising groups (in a manner of speaking) born: “I heard a mother of four, having coffee with four other mothers in a suburban development fifteen miles from New York, say in a tone of quiet desperation, ‘the problem.’ And the others knew, without words, that she was not talking about a problem with her husband, or her children, or her home. Suddenly they realized they all shared the same problem.” In the very anomic suburbs where Friedan had said women were alone.

Where Friedan’s solidarity arises from a commonality of unacknowledged interests, a shared situation that lacks only a story (and a storyteller), Frederick Douglass’s account of his escape from slavery reveals a more chance encounter between divergent interests. Walking along the Baltimore wharf one day, Douglass stopped to help two Irish dockworkers unload a ship’s wares. He struck up a conversation with them. When the Irishmen learned that Douglass was still enslaved, and would be for life, they counseled him to flee to the North where he’d find allies who could help him win and keep his freedom.

Years later, Douglass would report that it was this serendipitous solidarity of strangers that produced in him the resolve to escape slavery. Even under the most harrowing conditions, in which all manner of silence and separation is enjoined, men and women find ways to create connections and forge new solidarities. Not because they already enjoy democracy but because they are trying to create it.

If one half of the democratic project is to create bonds that are not there, the other half is to sever bonds that are there. Nora leaves Torvald, Douglass flees his master, workers walk out on the boss. Indeed, across the globe, the labor movement always has been a double movement of both solidarity and separation: on the one hand, creating a sense of identification and shared fate between workers in the face of repeated attempts by employers and the state to break those connections and keep workers apart; on the other hand, pressing workers to give up their connection to the boss. Breaking the bonds of established society, forcing men and women to separate and isolate from one another in this way, is never easy. Everything in law and custom conspires against it. It is made more difficult, as Susan B. Anthony recognized in her discussion of the challenges facing the women’s movement, by the warm and “friendly relations that exist between the sexes” and other social dyads.

Yet it is the very tightness of those bonds of oppression, the political scientist Frances Fox Piven suggests, that makes them such potent instruments of inauspicious democracy. The reason workers feel obliged to their bosses, wives to their husbands, debtors to their creditors, renters to their landlords, is not simply that workers and wives and debtors and renters face negative sanctions if they break their commitments. It’s that bosses, husbands, creditors, and landlords depend upon them. Superiors need the cooperation of subordinates in order to accomplish their aims. Society needs the cooperation of subordinates in order to accomplish its aims.

That gives those subordinates a tremendous amount of power, argues Piven. Power lies “in their ability to disrupt a pattern of ongoing and institutionalized cooperation that depends on their continuing contributions.” Disrupt that cooperation at the right moment in time, break those bonds and forge new ones, and democracy will be advanced: a union will be formed, a civil rights law will be passed, a division of labor in the family will be recast.

The premise of the tradition of inauspicious democracy, then, is that men and women are already in association, cooperating to produce the family, the economy, and society as a whole. That cooperation creates all sorts of negative consequences—patriarchy, poverty, environmental catastrophe, and much else—but the victims of these consequences seldom realize that they share a connection or common interest, or that their cooperation, and society’s dependence upon them, gives them potential power to deal with those consequences. Denied access to existing political institutions, they must find ways to discover that connection, that power. They must turn themselves, writes Dewey, from an “inchoate, unorganized” and “formless” collection into a self-conscious collective. They must “break existing political forms” and create new ones; they must destroy old connections and forge fresh ones. Democracy, in this account, is never “the product of democracy,” that is, of current political institutions. It is “the convergence of a great number of social movements” working to “remedy evils experienced in consequence of prior political institutions.”

*

When people express concern about the consequences of pandemic politics for democracy, they are thinking of a fairly familiar, and limited, repertoire of activities—voting, primaries, conventions, marching in the streets. But the counter-tradition of inauspicious democracy teaches us that the world of established institutions and familiar tactics, even if those tactics once belonged to protest movements past, is not the only place to look for democracy. It presses us instead to look at those networks of interdependency that Piven spoke of, to see how subordinate classes might use as leverage the dependence of their superiors (and society) upon these subordinates, to bring about a greater democratization of the whole.

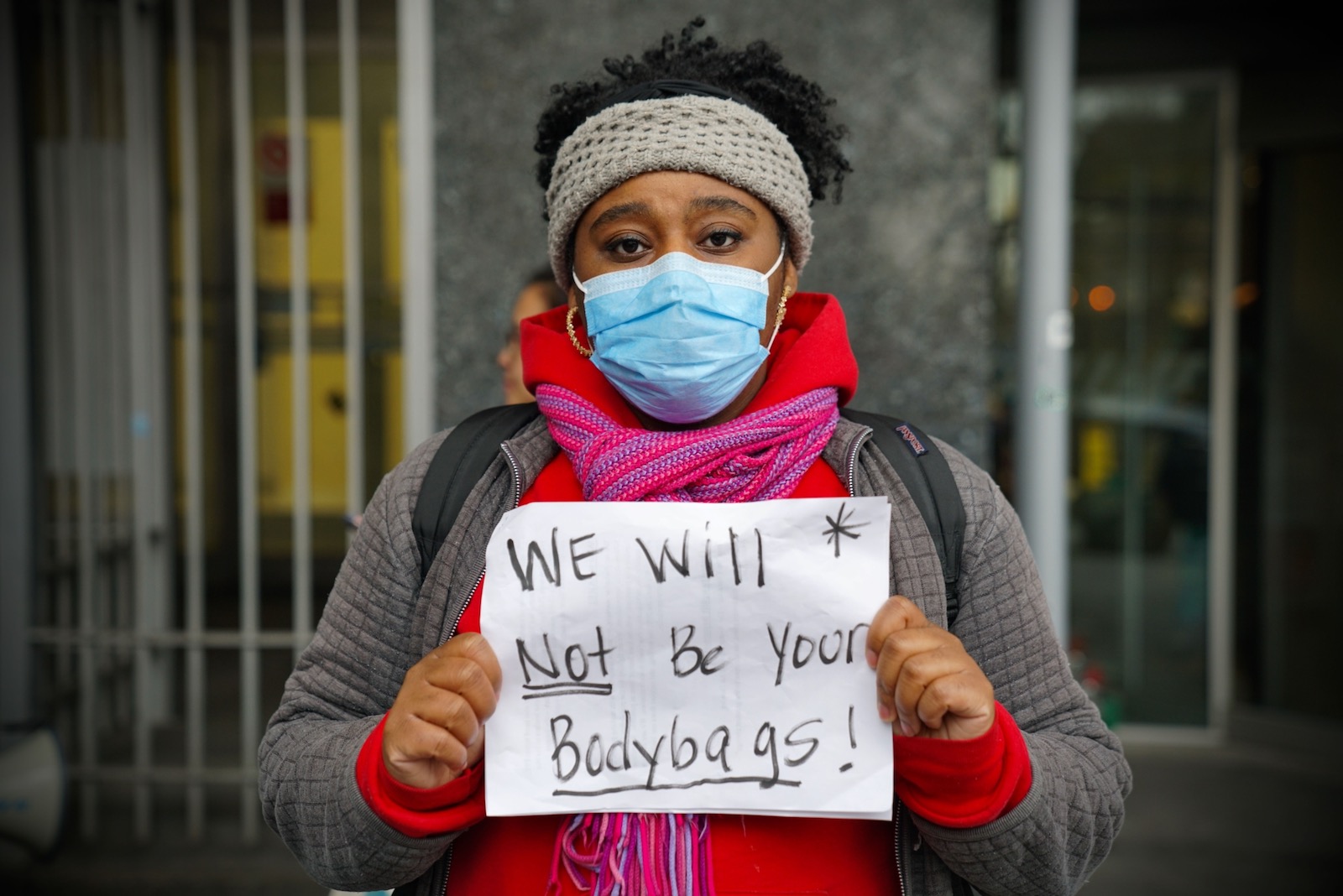

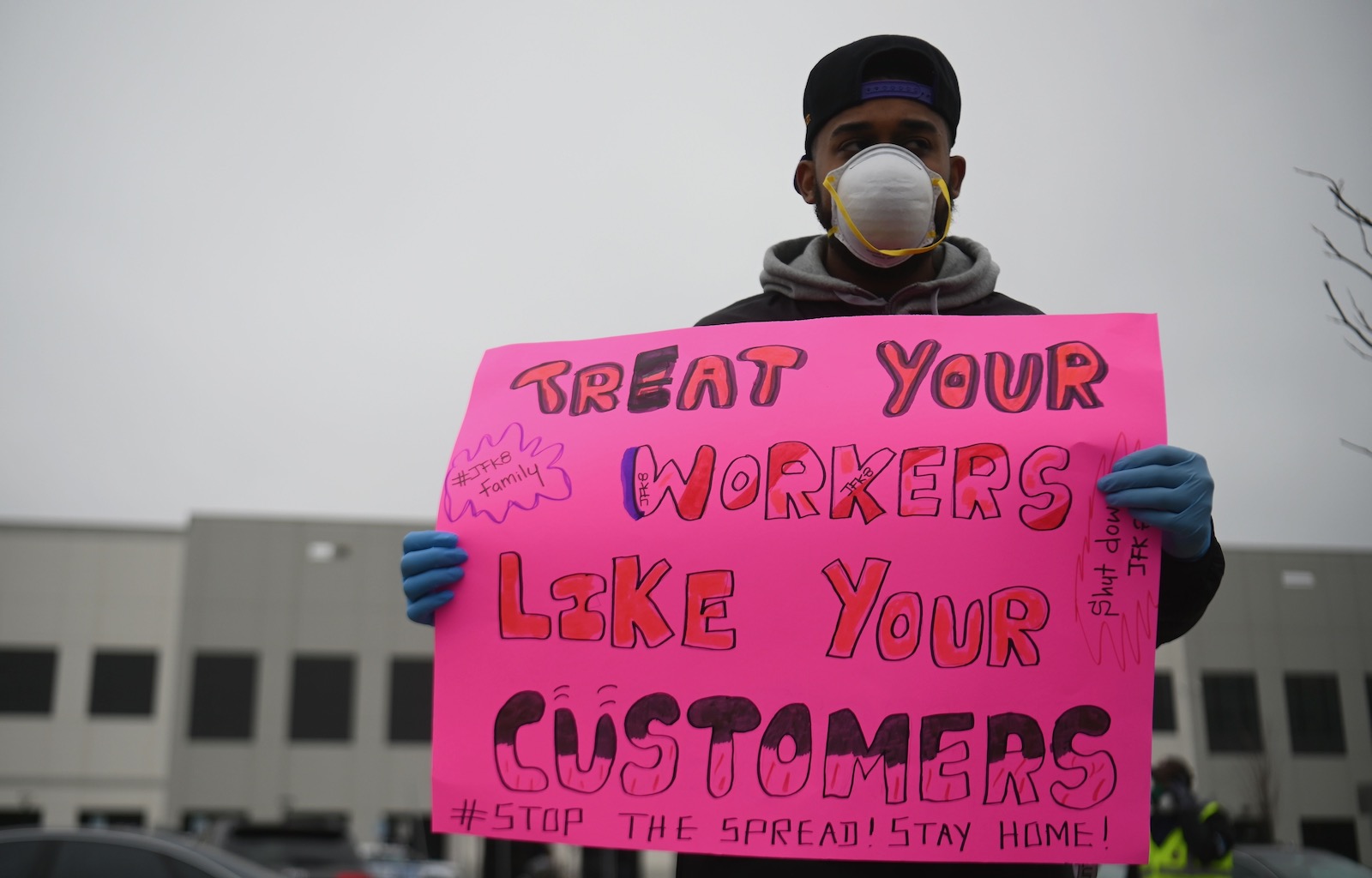

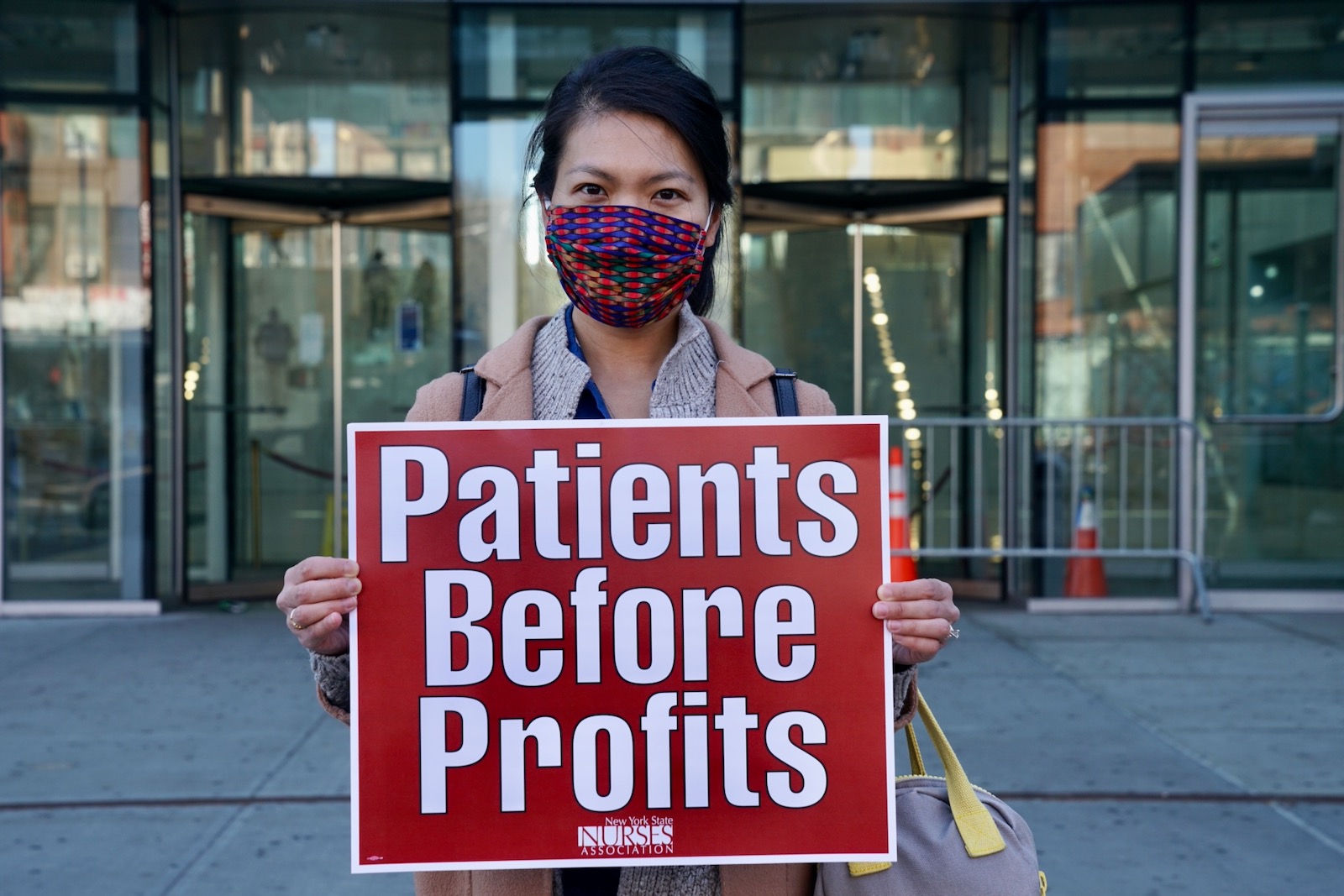

Isolation, it has been pointed out, is a luxury many men and women in the United States cannot now afford and will probably never enjoy. For many in the working class, and some in the professional classes, there is no withdrawal from public spaces to a place of greater safety at home. These men and women are picking lettuce, boxing groceries, delivering packages, driving buses and trains, riding buses and trains, filling prescriptions, operating registers, caring for the elderly, taking care of the sick, burying the dead. Though these disparities understandably arouse a sense of deep unease, and guilt among those who are their beneficiary, there is a dimension to this inequity that has gone overlooked. The state designates these men and women to be “essential workers,” and while that designation has earned those workers little more than a patronizing thanks for their “selflessness” from President Obama, Mayor Bloomberg, and other worthies, the designation is nonetheless a recognition of their potential power right now. Power that some have begun to wield.

Since the pandemic began, there have been a number of stories of workers organizing walk-outs, sick-outs, and pickets in which protesters remain in their cars and honk their horns, eventually bringing out the police. In some instances, these actions have been effective. In New York City, as Mayor Bill de Blasio and Governor Andrew Cuomo refused to close the schools, teachers, often acting in advance of their union, threatened to call in sick en masse. Although it’s been forgotten in the reporting that has conferred a halo on the New York governor’s leadership, journalists at the time acknowledged that these worker actions were forcing the state’s hand.

The sites of these actions have varied, but it is workplaces like Amazon and UPS and Instacart that get the bulk of the attention. There’s a reason for that. As shopping in person grinds to a halt, online ordering has skyrocketed. With business orders plummeting, residential orders are picking up the slack of what little there is left of the economy. That, again, puts these workers into an effective position not only to press their own demands but also to push for more measures to protect the public good.

While the bulk of these actions have been led by unions or activists within unions—in other words, people already adept at the politics of democratic solidarity—we’re also seeing new forms of organization in areas like housing, often in the most surprising circumstances. In Los Angeles, Saturn Management—named, presumably unwittingly, after the Roman equivalent of the Greek god who devoured his own children—sent out an email to the three hundred tenants who rent properties from the company across the downtown and west side of the city. Tenants throughout California had been calling for a rent strike; the email instructed Saturn’s tenants to pay their rent on time. Rather than bcc’ing all the recipients, however, the company including their email addresses. Without thinking, Saturn gave the renters both a common cause—creating a new constituency for action, in Dewey’s sense—and a means to communicate with each other about the cause. One renter, Roberto Torres, emailed his fellow tenants, “I’m just throwing out there—RENT STRIKE.” And then they organized a Google document and a Slack channel.

*

It would be foolish to understate the obstacles to democracy in America at the moment or to overstate these attempts to overcome those obstacles. The United States has seldom been an easy place to make change. It took the French an afternoon to storm the Bastille; it took American workers a hundred years to get a weekend. Yet it’s also true that solidarity, the connections that are created and sustain democracy, is often a story of surprise. Its most potent moments come, almost always, after a long and terrible night.

On one such night, that of January 18, 1945, the Germans evacuated Auschwitz, leaving behind only those too sick and diseased to be forced to march. Primo Levi was one of them. On January 20, Levi and two men managed to lift themselves from their cots, go outside, and salvage a heating stove, fuel, and two sacks of potatoes. They took their treasure back to the hut that passed for an infirmary. The men in the hut decided to award Levi and his mates each a slice of bread.

It was an unthinkable act of cooperation. The camps allowed no room for fellow feeling, much less sharing. According to Levi, “The law of the Lager said: ‘eat your own bread, and if you can, that of your neighbor.’” Politics begins the moment such laws, which have the force of nature, are suspended—and democracy, when they are suspended in egalitarian acknowledgment of the contribution of each to the social production of all. When that bread was shared, says Levi, he realized that a new and unexpected bond, born of gratitude, had been created among the prisoners. “It really meant that the Lager was dead.”