In June, when Mexico holds its fifth federal election since the end of one-party rule, Claudia Sheinbaum is almost certain to be elected president. An environmental scientist and former mayor of Mexico City, Sheinbaum is affiliated with the incumbent Movement for National Regeneration, or Morena. Most polls give her a double-digit advantage over the main challenger, Xóchitl Gálvez, a businesswoman and former senator nominated by a center-right coalition of opposition parties, Strength and Heart for Mexico. The third candidate is Jorge Álvarez Máynez, a congressman running under the auspices of a smaller organization, the Citizens’ Movement, or MC.

Sheinbaum is likely to win for a simple reason: she has the blessing of the current president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, or AMLO. Surveys, which are typically very politicized, show that many Mexicans are disappointed in López Obrador’s administration; he has achieved modest reductions in poverty but failed to deliver on his promise of social transformation. But their disillusionment does not extend to the man himself. The president is poised to finish the single six-year term allowed by the Mexican Constitution with high approval ratings; the figures range from 50 to 70 percent.

His endorsement amounts to a coronation. A vote of confidence from such a beloved figure is enough to convince many, if not most, citizens. Not to leave matters to chance, Morena has openly, and at times illegally, thrown the weight of the state apparatus behind Sheinbaum’s campaign—a widespread practice across the political spectrum that López Obrador denounced during his two unsuccessful bids for the presidency in 2006 and 2012.

If López Obrador’s popularity is a boon to Sheinbaum during her campaign, it might well pose challenges once she’s in office. For Morena is less a disciplined political party than a collection of contradictions held together by personal loyalty to AMLO. President Sheinbaum would have to chart her own course without alienating her predecessor—a potentially difficult balancing act.

*

Elections in Mexico used to be administered by the Secretariat of the Interior—which is to say, by the Party. This system was put in place in the 1920s by the Sonoran generals who seized power at the end the Revolution. Taking inspiration from Soviet Russia and Mussolini’s Italy, rather than the United States, they formed the organization that would later come to be known as the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI. This “total party” was to “incorporate” the various “sectors” of Mexican society: trade unions, the peasantry, the army, students, landowners, industrialists, and so on. Party intellectuals maintained that by including different sectors, the PRI had forged a distinctively Mexican form of democracy, one that rendered free elections unnecessary.

The principle underlying this corporatist structure was that power would be transferred not through violent means—as had been the case since the collapse of Porfirio Díaz’s dictatorship in 1910—but through “institutional” means. Presidents would be limited to a single, six-year term—the so-called sexenio—with no possibility of reelection. In the decades that followed, presidents chose their successors, some handing power to a different faction within the PRI, but none ceding the party’s authority.

This model rested on an unspoken agreement between the PRI and the growing middle classes: do not make a fuss about democracy and in return we will raise your standards of living. The pact held as economic growth lasted through the 1940s and 1950s, but it slowly came apart in the downturn that followed. In 1968, large student protests, organized in part by communists, panicked the regime, which responded by killing scores of civilians in Mexico City.

Around the same time, the Catholic capitalists of Northern Mexico, who had always resented the PRI’s redistributive policies and anti-clericalism, organized to field conservative candidates. They did so first in local and later in federal elections, under the banner of the National Action Party, or PAN. In the southern sierras, impoverished campesinos, tired of state neglect, launched a guerrilla war against the government. In time the creation of an independent electoral authority became a rallying cry for the PAN as well as for the Unified Socialist Party of Mexico, or PSUM, whose members had an important part in designing the institutions that later brought down the regime.

As pressure mounted, the PRI was forced to seat a handful of PSUM members in the legislature and recognize the victories of a few panista gubernatorial candidates. The party’s grip on power grew more tenuous amid the economic crises that followed the collapse of oil prices in the 1980s and the start of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994. Eventually it agreed to the opposition’s demands and ceded control of elections to an independent authority: the ancestor of the present-day National Electoral Institute, or INE. The free elections of 2000, won by the PAN’s Vicente Fox, inaugurated what came to be known as the “Democratic Transition”—a period of political liberalization that began in hope and ended in disappointment. The governments of these two decades proved incapable of addressing existing problems (notably poverty) and efficient at creating new ones (notably violence).

Advertisement

Perhaps the gravest error was made by Fox’s successor, fellow panista Felipe Calderón, who deployed the army on an offensive against drug cartels, disrupting the tense equilibrium that had incentivized criminal organizations to keep a low profile. The mafias, which until then had competed as commodity exporters in the shadow economy, became factions in a full-on civil war. Insecurity was worsened by neoliberal policies that further eroded the welfare state, a process that had begun with NAFTA. Corruption, too, proceeded as before. During her husband’s presidential term, which lasted from 2012 to 2018, the wife of the PRI’s Enrique Peña Nieto thought it advisable to purchase a strikingly affordable mansion from a construction firm that also vied for government contracts. As a result of all this, many grew disillusioned with the new political class and turned to a man who promised to do things differently.

*

Born in 1953 to middle-class second-generation Spanish immigrants who had settled in Tabasco, an oil-rich state on the southern end of the Gulf of México, López Obrador began his political career in the old PRI. Having risen through the ranks to become the president of the party’s branch in his home region, by the 1980s he was growing disillusioned with its drift toward neoliberalism. In 1988, along with many future members of Morena, he left the PRI to join the left-wing Party of the Democratic Revolution, or PRD. In 2000 he was elected mayor of Mexico City. He presided over a moderate social-democratic administration that established welfare measures, such as a pension for elderly people, which made him popular enough to position himself as the PRD’s presumptive candidate in the 2006 presidential election.

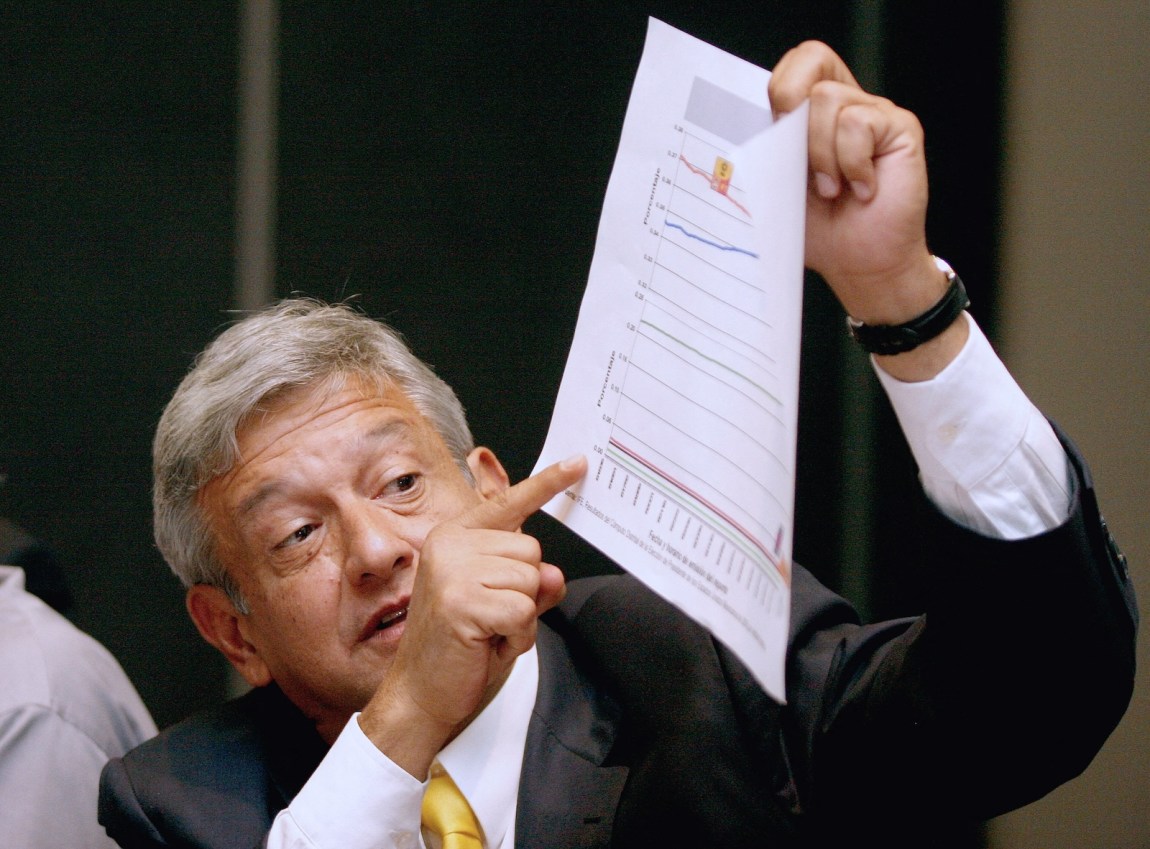

The business elite and the politicians of the PAN and the PRI watched AMLO’s rise with concern. As the election approached, the federal legislature, where those two parties held a majority, summoned him to answer frivolous impeachment charges—related to the expropriation of a tract of land to lay out an access road for a hospital—that could have barred him from running for president. López Obrador survived the trial but never forgot the affront. His resentment only deepened when the election authority declared that he had lost the election to Calderón by less than a percentage point. Convinced he’d been a victim of fraud—a belief shared by many citizens—AMLO denounced the results. He competed again in the 2012 election but lost to Peña Nieto by a large margin.

Later that year, López Obrador resigned from the PRD and founded his own party, Morena. He cast himself as an outsider, even though he had spent most of his career within the political establishment. Running for president in 2018, he campaigned on sending the army, which Calderón had unleashed on the cartels, back to the barracks; bringing the welfare policies that had made him popular in Mexico City to the rest of the country; and above all rooting out the elite that had conspired against him in 2006. His campaign succeeded in harnessing the widespread discontent with Peña Nieto, who was mired in corruption scandals.

AMLO claimed that he would vastly increase social spending without raising taxes: recovering the sums lost to corruption would offset the expense. This last idea neatly encapsulates the paradoxes of his politics. López Obrador calls himself a leftist and never misses an opportunity to lambast his adversaries as “conservatives” and “neoliberals,” but some of his positions are closer to Ronald Reagan’s than to Salvador Allende’s. The consequences of this tension would become bitterly clear after he won the 2018 election with 53 percent of the vote, beating his closest rival by nearly thirty points.

Ratifying a new version of NAFTA, detaining thousands of refugees from Haiti, Venezuela, and Central America before they could claim asylum in the US, framing addiction as a moral problem rather than a public health issue—the litany of President López Obrador’s right-wing policies is tiresome to recite. Perhaps his worst betrayal was cozying up to the military. AMLO went as far as stymying the investigation into the 2014 case of forty-three students from the Ayotzinapa Normal School, a teacher’s college in rural Guerrero, who, a team of international experts has concluded, had been “disappeared” by criminal groups with the army’s support (at this point it’s all but certain that the students were killed). If anything the president has expanded the armed forces’ role in public life. Besides fighting the cartels, they now run a growing portfolio of state-owned businesses, ranging from civilian airports to a tourist railway. They are also building several luxury resorts, one to be located at the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve, which the United Nation has recognized as a protected Natural World Heritage Site. It produces 13 percent of the Earth’s oxygen.

Advertisement

Here one can see another aspect in which AMLO is closer to the right than to the left: his indifference to the threat of climate change. In his daily press conferences, which last as long as three hours, he often lambasts activists, many of them Indigenous, who oppose his infrastructure projects in Calakmul and other fragile ecosystems as “traitors to the fatherland.” The accusation is doubly galling when one considers that in 2022 alone, over thirty-one environmentalists were killed in Mexico—the third highest number in the world.

His denialism is grounded in the belief that state-led development is the ultimate answer to the ills of a nation. The way to lift Mexico out of poverty is to build infrastructure: railways, pipelines, and apparently, resorts. From this perspective, environmental concerns are at best trivial and at worst betrayals of the national interest. After all, the First World developed its economy by destroying Mother Nature. The problem is that the climate crisis knows no borders and will hurt developing nations worst of all.

Nowhere is AMLO’s irresponsible attitude to climate change more visible than in one of his beloved megaprojects: a new oil refinery in his native Tabasco. Having so far cost close to 19 billion dollars—nearly two and a half times its original budget—it has yet to refine a single barrel, even though the president held an inauguration ceremony two years ago. The project, which the government claims will finally begin operations this month, is supposed to serve as a lifeline for Petróleos Mexicanos, or Pemex, the once-mighty state oil company whose 106 billion dollar debt, the largest of any oil firm in the world, recently led Moody’s to downgrade its credit rating to B3—what most investors consider “junk.”

But the new refinery will not save the Mexican oil industry. The first thing I learned during my stint as an oil reporter for Reuters is that the Gulf Coast has a surfeit of refineries, making the market extremely competitive. There is no reason why refining oil at the new plant would be cheaper than importing gasoline from Texas, which perhaps explains why in 2021 the López Obrador administration purchased a refinery in that state.

The project is also supposed to cement Mexico’s “energy sovereignty”: its ability to meet most of its gasoline and electricity needs through domestic production. That might seem like a noble goal. But given what we know about climate change, the state would be irrational to invest so much money in a new refinery that will only break even if Mexicans burn gasoline for decades to come.

These are not AMLO’s problems to solve. Soon to be out of office, he plans to retire to his hacienda and leave public life. But he would not take well to his successor dismantling the oil-centered agenda of state development that he sees as an essential part of his legacy. This is one of many dilemmas that Claudia Sheinbaum would inherit as president.

*

Sheinbaum, born in Mexico City in 1962 to an upper-middle class family of academics, was exposed to leftist ideas from a young age: a video shared by her campaign shows her, at ten, singing the classics of nueva canción, a folk-revival genre associated with the Cuban and Nicaraguan Revolutions. Though the international press highlights her Jewish roots—she is the granddaughter of refugees from Bulgaria and Lithuania—she herself downplays her heritage. At least once she has appeared in public wearing dresses embroidered with the Virgin of Guadalupe. At the National Autonomous University of Mexico, Sheinbaum joined a student group that became the youth wing of the PRD. In 2000, when López Obrador was elected mayor of Mexico City on that party’s ticket, he named her as his Secretary of the Environment; when he broke with the PRD, she joined Morena. In 2015, under the new party’s auspices, she was elected head of the Mexico City borough of Tlalpan, and in 2018 mayor of Mexico City.

The results of Sheinbaum’s mayorship were mixed. Taking a cue from the social policies that made AMLO popular, she established “universal scholarships” that paid public school students a cash stipend. But she also oversaw a catastrophic response to the Covid pandemic; Mexico City had one of the highest excess mortality rates of any metropolis in the world. (At one point the municipality sent those infected with the virus a package with doses of ivermectin, a pseudoscientific treatment for the disease.) The low point of her administration came in May 2021, when an elevated section of the subway collapsed, killing twenty-seven people.

Along the way, Sheinbaum earned a reputation for intransigence even within her own party. Many in Morena believe that the internal selection process that led to her nomination was rigged and resent her status as dauphine. Some factions—notably the one led by Clara Brugada, now running to take over her old mayorship—are increasingly hostile to her. She’s not a gifted retail politician: a video that shows her impatiently dismissing sympathizers who wanted to speak with her circulated widely on social media. After her party’s lackluster performance in the 2021 local elections in Mexico City, she began speaking slowly and adopted an incongruous tabasqueño accent that struck many as a desperate attempt to sound like López Obrador.

Sheinbaum has tried to follow her mentor’s lead in other ways as well. The slogan she adopted during Morena’s internal selection process was Continuidad con cambio—continuity with change. The contradictions implicit in that tagline are acute. While AMLO’s near-fanatical embrace of state development has led him to bet all his chips on fossil fuels, Sheinbaum dedicated much of her academic career to studying ways to minimize greenhouse emissions without sacrificing the welfare of impoverished Mexicans. One suspects she is well aware that her mentor is anachronistic in his fixation on oil as the “blood of the nation”—a commonplace of Mexican leftism ever since Lázaro Cárdenas, the PRI’s lone socialist president, expropriated foreign oil interests in the 1930s. The problem is that the personal loyalty that AMLO commands from both the party and the electorate would make it difficult for her to correct course.

This dilemma has offered an opening to Sheinbaum’s main opponent, Xochitl Gálvez, who grew up in an Indigenous Otomí working-class family in Hidalgo. She studied robotic engineering, founded several businesses, and then entered entered public life in 2000, when the PAN’s Fox, anxious to fill his pro-business government with names untainted by the PRI, tapped her to lead the agency charged with Indigenous affairs. She later served as head of the Mexico City borough of Miguel Hidalgo. In 2018 she was elected to the Senate on the ticket of the coalition formed by the PRI, the PAN, and the PRD—the same that nominated her to the presidency this year.

Many observers believe the opposition chose Gálvez over the blue-eyed panista Santiago Creel because AMLO has succeeded in shifting the country’s political center to the left: a woman with humble roots made for a more attractive alternative to Sheinbaum. That the candidate is a pro-choice Catholic given to folksy outbursts of expletives also helps. At her best Gálvez is ecumenical and charming. But she’s also prone to putting her foot in her mouth: her attempts to please both feminists and the PAN’s conservative wing by equivocating on abortion have alienated both camps.

Perhaps sensing an opportunity to attract progressive voters who would otherwise be turned off by her longtime affiliation with the PAN, Gálvez has made it clear that her energy policy would be radically different from Sheinbaum’s. She plans to diversify Pemex’s operations to include plants powered by cleaner sources of energy. This proposal sounds great on paper. But remaking Pemex into a clean-energy company would require convincing investors to lend vast amounts of money to a decrepit firm.

Besides, Gálvez would have a difficult time securing legislative approval to fund her ambitious designs, given that the coalition that nominated her is a political chimera. Her fellow travelers include the Catholic businesspeople of the PAN, the rickety remnants of the PRI, and the hollowed-out shell of the PRD. These parties dominated Mexican politics as rivals for the first eighteen years after the end of one-party rule. But AMLO’s landslide victory in 2018 weakened them to such a degree that they were forced to form an unholy alliance. The result is a negative image of Sheinbaum’s predicament: Gálvez must appeal to voters who have little in common save their rejection of López Obrador.

The tendency of Mexican politics to bring together strange bedfellows can also be discerned in the smaller organization that has fielded a third presidential candidate: the Citizens’ Movement. In an earlier incarnation, the MC was part of the leftist coalition that nominated AMLO to the presidency in 2006. Today its most successful politicians are best described as centrists, among them Enrique Alfaro, the governor of Jalisco, and Samuel García, the governor of Nuevo León. But the movement’s presidential nominee, Jorge Álvarez Máynez, insists that the MC represents the only social-democratic option in the current election.

It’s true that a number of exciting young leftists are running under the organization’s bright-orange banner. One who stands out is Valeria López Luévanos, a twenty-eight-year-old former councilwoman from Matamoros, in the northern state of Coahuila, who has told me that she left Morena after concluding that the party had betrayed its ideals. Still, the twists of Álvarez Maynez’s own career illustrate his movement’s ideological flexibility: the son of a founding member of the Communist Party of Mexico, at nineteen he was elected to the city council in Zacatecas on the PRD’s ticket; at twenty-five he won a seat in that state’s legislature under a coalition that included the PRI; at twenty-seven he switched his affiliation again to compete for Congress with the MC.

The Citizen’s Movement has been described as a “franchising party” whose local branches differ from one another despite sharing the same name. In Jalisco, one of two states where the MC is dominant, the party is widely seen as the personal fiefdom of Governor Alfaro, a career politician who has violently repressed protests. In Nuevo León, the MC looks more like Governor García: a brash, pro-business thirtysomething from an elite background who has at different points declared his support for reproductive rights and asked the Supreme Court to rule that life begins at conception. In Mexico City, MC Congresswoman Patricia Mercado, a feminist who once ran for president, is perhaps the politician with the best socialist bonafides in Mexico.

But this geographic diversity comes at a cost. For all its strength in certain pockets of the country, the Movement is unlikely to make a strong showing in the national election: most polls record that between 2 and 5 percent of voters are leaning toward Álvarez Máynez. It would seem that the “franchising party,” like Culver’s and Waffle House, is very much a regional chain.

*

Today some members of the opposition worry that AMLO is attempting to restore the old regime, with Morena in place of the PRI. Their fears are rooted in López Obrador’s hostility toward the institutions that allowed for his own rise to the presidency, above all the INE, which he tried to disempower three times using constitutional amendments. The first attempt died in Congress; the second was struck down by the Supreme Court; the third is currently under legislative consideration but is unlikely to pass. One gets the sense that AMLO believes that free elections are desirable in theory but that a benevolent party needs to protect the popular will until the rotten elites he accuses of stealing his victory in 2006 are neutralized.

AMLO’s hostility to electoral fairness takes concrete form in the sort of chicanery that Nixon might have described as “ratfucking.” Campaign advertisements, for example, are forbidden by law until twelve weeks before the election takes place, in this case on June 2. Long before the start of this period, however, fences around the country were hand-painted with a surprisingly uniform design: the outline of Sheinbaum’s face and the hashtag #EsClaudia. In a display of cynicism that reminded many of the PRI, Morena claimed that the banners were the spontaneous work of citizens.

Elected officials and public servants affiliated with Morena have reportedly forced their subordinates to donate as much as 10 percent of their wages to fund party campaigns. Morenista apparatchiks have also instructed state employees to attend demonstrations in support of AMLO—a practice known as acarreo, or herding. Theoretically neutral state-owned media, such as the TV stations Canal 11 and Canal 22, do not hide their support for Sheinbaum. Private media operations that receive large amounts of government money—such as La Jornada, a daily newspaper in Mexico City, and El Chamuco, a magazine edited by a group of cartoonists who are personal friends of the president—breathlessly praise AMLO while relentlessly attacking the opposition. All of this has made for what some commentators call la cancha dispareja: an uneven playing field.

Morena’s insistence on bending the rules can seem perplexing. It’s not clear that the party needs to cheat in order to win. Some members of the opposition suspect AMLO has concluded that, even if Sheinbaum could prevail while adhering to the INE’s rules, it’s safer to defang unelected electoral bureaucrats, lest the “conservatives” and “putschists” within their ranks succumb to their well-known tendency to defraud the people’s candidates. In other words, they see the president as suffering from a form of paranoia. “It would seem that AMLO doesn’t need all these dirty tricks to secure a victory for his party,” Carlos Loret de Mola, a prominent journalist who is widely seen as part of the opposition, wrote in the Washington Post in 2023. “It’s illogical for him to preemptively taint a much-predicted victory.”

López Obrador’s efforts to undo the legacy of the Democratic Transition are deeply concerning. But by fixating on his animosity against electoral institutions, the opposition risks distracting public attention from the crisis that, to my mind, poses the most serious threat to Mexican democracy: the wave of violence that has gripped the country since Calderón’s term.

*

Mexico has contended with powerful criminal organizations since at least the early twentieth century, but their central place in national life is a recent phenomenon. The old PRI made informal agreements with interest groups, including organized crime. Every now and then the regime cracked down on drug traffickers to please its American allies, but for the most part it turned a blind eye and allowed the mafias to move their wares to lucrative markets in the US. In return it expected kickbacks—but also that criminal organizations refrain from attacking civilians.

This system was dismantled during the Democratic Transition. The situation began to deteriorate rapidly under Calderón, whose military offensive against the cartels was widely seen as an attempt to legitimate his disputed electoral victory over AMLO. The conflict that ensued didn’t just pit the state against criminal organizations, it pitted the different organizations against one another in a civil war that has so far claimed nearly over 360,000 lives. Between 2007 and 2023, the murder rate skyrocketed from 8.1 to 25 killings per 100,000 people.

Calderón’s offensive forced criminal actors to antagonize the government in the open. They soon decided to displace or at least capture the state apparatus. The line between the Mexican government and mafias had long been blurry, with cartels bribing public servants from rank-and-file cops all the way up to cabinet secretaries. In recent years, however, criminal organizations have sought to exert control over the territories where they operate by meddling in elections. Sometimes these attempts at cooptation take the form of illegal campaign financing. At others the mafias simply execute candidates who might threaten their interests. One hundred and thirty-two politicians were killed during the 2018 election, and another 102 in 2021. In the first two months of 2024, at least thirty-three politicians have been murdered—a number that is certain to increase.

Today, there’s virtually no figure in Mexican politics who hasn’t been tainted by accusations of improper dealings with the cartels. As ProPublica and The New York Times recently reported, the United States Drug Enforcement Administration—an agency that many in Mexico distrust—investigated allegations that a number of cartels contributed millions of dollars to López Obrador’s presidential campaigns in 2006 and 2018. The journalists’ DEA sources claimed that they had shelved the case, which did not lead to any charges, to avoid the impression that America was meddling in an ally’s internal affairs. López Obrador, who denies all allegations, responded that the news reports themselves constituted such meddling. He also read the cell phone number of one of the two Times reporters, Natalie Kitroeff, out loud during his daily press conference. His decision to doxx the correspondent is not only shameful but dangerous: Mexico is one of the deadliest countries in the world to be a reporter. In 2022 eleven journalists were killed on the job.

In these circumstances, the most concerning aspect of the presidential campaign may well be that the candidates have put forward inadequate proposals to address organized crime. Sheinbaum proposes establishing outreach programs to keep young people from joining criminal organizations (AMLO tried something similar with an apprenticeship scheme that never took off), amending the Constitution so that Supreme Court justices and other judges are elected by the popular vote (an AMLO initiative that is somehow meant to end corruption in the judiciary), and expanding the National Guard (the militarized law enforcement force that AMLO set up after disbanding the civilian Federal Police).

Gálvez has echoed Calderón, saying that she would unleash “the full force of the state” against organized crime by, among other things, building a new maximum-security jail reminiscent of the house of horrors that is now the crown jewel of Nayib Bukele’s prison system, where he has imprisoned 2 percent of El Salvador’s population. Álvarez Maynez advocates regulating drugs instead of prohibiting them, professionalizing civilian law enforcement, and promoting alternatives to criminal justice—sensible policies that are unlikely to rein in organizations whose firepower and revenue exceed those of many small nations.

*

June 2 will be a landmark day for Mexico: for the first time, a woman will be elected president. But the date will also be historic for marking the fourth and last time that Mexicans cast a vote for or against López Obrador in a presidential race. While his name won’t appear on the ballot, the election is about him more than about Álvarez-Máynez, Gálvez, and even Sheinbaum—it is a referendum on his legacy.

And what is that legacy? At the level of material reality, Mexico remains for the most part the same country that it was in 2018. By some measures (labor rights, the minimum wage), it is slightly better off; by many others (violence, democratic integrity), things have gotten much worse. But, as psychoanalysts know and game theorists pretend not to know, people rarely make consequential choices on the basis of a rational assessment of the facts at hand. Come June, barring some drastic and unexpected event, a president who betrayed his promises will hand power to a chosen successor from his party.

Then again, there’s one sense in which López Obrador has, in fact, transformed Mexico. He rose to power on the masses’ rejection of the regimes of the Democratic Transition, which were controlled by neoliberal economists and law-and-order reactionaries and kleptocrats in well-cut suits. Now there’s no going back. After López Obrador, even the right wing has found it necessary to nominate a woman.