This article is part of a regular series of conversations with the Review’s contributors; read past ones here and sign up for our e-mail newsletter to get them delivered to your inbox each week.

For nearly two decades, Jerome Groopman has been writing for The New York Review of Books about all matters medical. In our latest issue, he reviews Andrew Leland’s memoir, which recounts the writer’s experiences as his eyesight declined. “The history of blindness is marked by humiliation and exploitation,” Groopman writes, but also by “liberation, epitomized by the development of braille.”

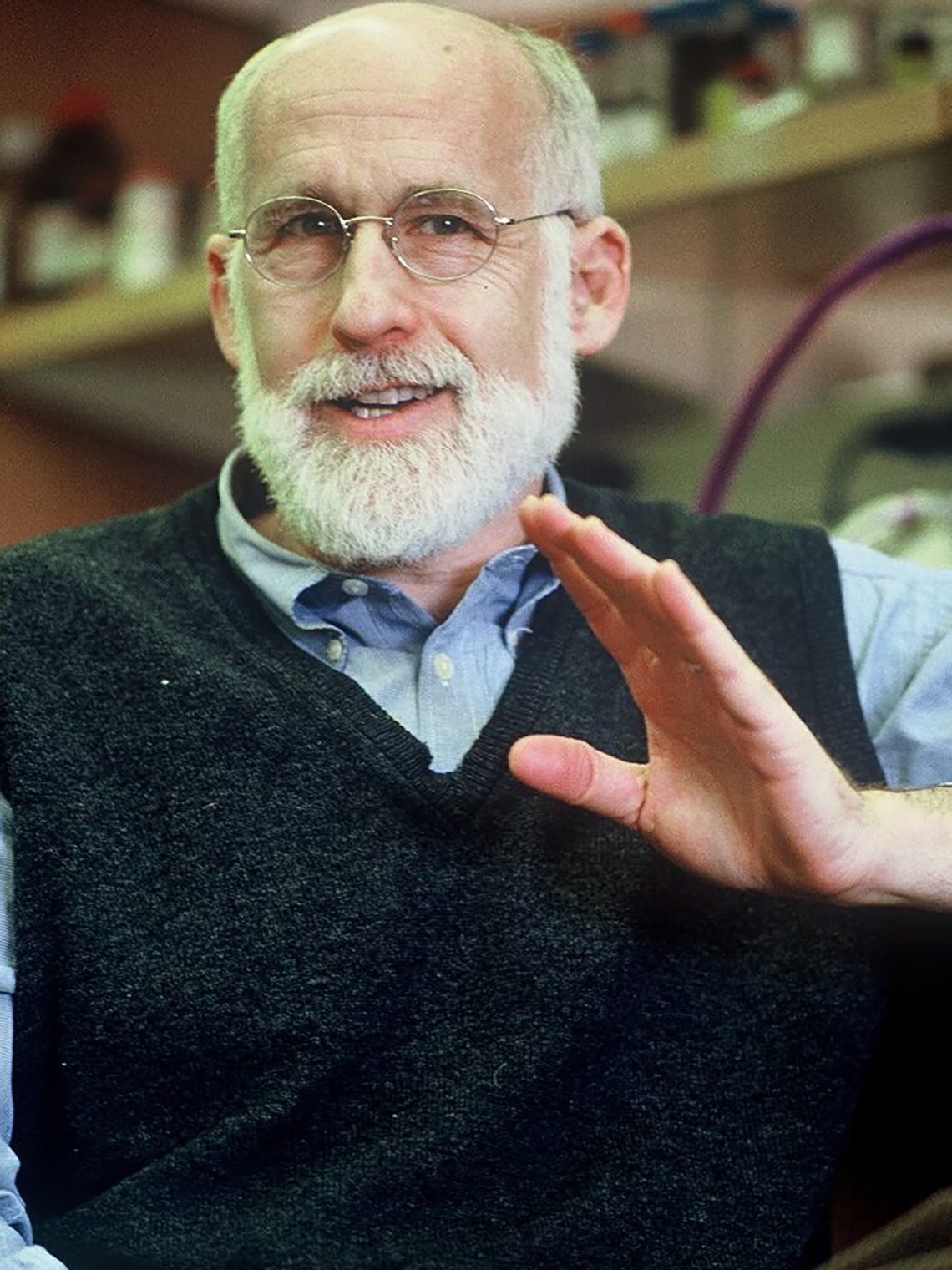

From autism to cancer to the healthcare crisis, Groopman treats his world-spanning, visceral subjects with sensitivity. He writes from an expert position: he is a practicing doctor, a medical researcher, and a professor at Harvard Medical School. We spoke this week about his wide-ranging career, the importance of genetic research, and (of course!) Oliver Sacks.

Nawal Arjini: What brought you to medicine?

Jerome Groopman: It was primarily a desire to be near people and do something in which science was brought to bear. At Columbia I double-majored in chemistry and political philosophy. I wasn’t sure which one to pursue, which one would be most gratifying. To be honest, the Vietnam War was going on, and my draft number was six, out of three hundred and sixty-five. If you went to med school you got a deferment, and that was certainly in the equation.

Did you hope to combine chemistry and political philosophy in some way in your medical career?

Chemistry requires synthetic thinking. You have to bring disparate pieces of knowledge together in order to look for a chemical structure. Political philosophy, to some degree, also involves disparate aspects of knowledge: economics, sociology, history, pure philosophy. I found that in medicine, you don’t have an answer when you start out. You’re looking for clues that are often distributed in different places: family history, as there might be a genetic predisposition; social history, because the person smoked or was exposed to a toxin; the physical examination, where you find that an organ might be disordered. Add to that the blood test, the CAT scan, all of it, but most importantly, the person, the psychology of the person you’re dealing with. It’s the same kind of synthetic process as political philosophy, but in a different dimension.

I imagine that leads quite naturally into writing.

Exactly. When I started out, I would do fifteen drafts before I was brave enough to have it seen by someone. My wife would joke that I spent four hours changing one comma. Writing, especially the kind of writing that I do, brings together narrative, science, sometimes history, and an appreciation for the person who might be at the center of the narrative.

How did you begin writing?

I didn’t begin writing until I was in my mid-forties. I followed a typical academic trajectory where I had a laboratory for research, I had patients, I was teaching medical students, and so on. In my mid-forties, I was taking care of people with serious blood diseases, cancer, and AIDS. There was a lot of suffering. I had absorbed a lot of that suffering. I needed an outlet, some catharsis, and I thought writing might be the way to find that.

The first essay I put together was a series of narratives about different patients, including a very wealthy investor who had been diagnosed with terminal cancer. He had come into my office, banging his fists on my desk, saying, “This is bullshit. I’m not going to die. You’re supposed to be smart. You figure out how to cure me.” I was in a very difficult position because I wanted to consider his will to live, his right to be treated, but on the other hand there was no established treatment for him, and I didn’t want to be a cowboy shooting guns all over the place to protect his own ego. That essay was seen by Tina Brown, who was at The New Yorker then, and she said, “This is hot.” So they published it. Their medical writer at the time had just died. It turned out that Brown wanted more, and they made me a staff writer, which was a great honor.

The greatest influence on me was Oliver Sacks, because he could capture people as people, and he always integrated serious science into his pieces. The two subjects that were most prominent for him, as I once wrote for you, were identity and adaptation: Who is this person, despite their illness? How does that illness interface with their behavior and their decisions, how do people perceive them from the outside, and how do they try to find meaning and adapt to what looks like a disability, but sometimes—not always, but sometimes—gives them hidden strength? Sacks was also a person of tremendous generosity of spirit. He blurbed my first book; I didn’t know him, and not every writer wants to see another writer come into their space. (Not that writers are competitive!) He represented to me both mind and heart.

Advertisement

How do you balance the narrative aspect of writing with communicating the nuances of the science?

I teach a freshman literature course at Harvard, and I try to show the students how to bring the science to life, not just to list facts. The challenge is to make the science accessible and show how it’s linked to the patient’s life. Sometimes the science falls short. In my review of Leland’s memoir, there’s a lot of research about genetics and how genes operate in different settings, but retinitis pigmentosa is an incredibly complicated illness from a genetic point of view. There are so many different mutations that can result in blindness, so how you tackle it, clinically, is really hard.

It’s not impossible, but I wanted the science to be there, to show a glimmer of hope: other forms of blindness are being treated genetically. But as Leland says, he doesn’t know whether this is going to result in a substantial improvement in his condition, it’s just something he holds onto. Even if there are ten people with the same genetic mutation, the illness doesn’t follow the same course in each of them. With retinitis pigmentosa, some people don’t become totally blind for decades. That was enough for Leland to hold onto. I wanted to be honest about the science, but also about how I would look at him as a patient.

How do the different parts of your work—writing, teaching, patient care, research—interact?

Seeing patients inspires laboratory research, because you see the unmet needs. I had patients with hepatitis C, which used to be fatal in a lot of people, and transmissible; I had part of my lab pursue that pathology, but eventually another lab created a treatment that completely cures it.

Does having worked on diseases like hepatitis C, cancer, and AIDS, the treatments for which have gotten so much better over the past decades, leave you feeling hopeful about the progress of medicine?

I’ve gone from witnessing the depths of disability and death, like with AIDS: I saw some of the first people with AIDS in California, in 1982 or so. The average lifespan was six months. They were mostly young gay men, and it was devastating, the infections they got, the cancers they got. Now, with all the new drugs that have been developed, someone who gets HIV is projected to have a normal lifespan. From six months to fifty years: it’s miraculous. There are still plenty of diseases that have unmet needs. But that’s part of what keeps you going: the belief that things can advance in a meaningful way.

You have an unusually public-facing job for a doctor. How do you see the relationship between regular doctors and doctors like yourself? What about the relationship between doctors and public health institutions?

There needs to be a very tight partnership between public health and individual patient care. You need to respect individuality. But the public-health people face a daunting problem, which is to get accurate information to people, to the people who are against vaccines, or who said Covid was just the sniffles while people were dying left and right. Without that, without the work of public health organizations, you’re really swimming against a very tough current, and I don’t envy them that work. There are people I’ve cared for who have misinformation and believe in conspiracy theories, but it’s really tough to change behavior when you deal with it on a societal level.

Are there any major or interesting medical stories that the public doesn’t know enough about?

The idea of genetic treatments. Often when people hear the words “genetics” or “DNA” or “RNA,” they shut down. The challenge is how to make it accessible. There’s a wonderful line in the Talmud that says, “Whoever saves a single life saves the whole world.” There might be only a few hundred people in the whole country who have a particular genetic disorder. It’s not sufficiently appreciated how hard it is to mobilize resources, or share resources, in order to help them.

The National Institutes of Health—I like them a lot. The joke back in the day was that it stood for Not Invented Here. But early sharing of data is crucial. The way to do that is through the instrument of money: if, as a researcher, you’re funded by a government, you should be obligated to post the information you’ve developed as quickly as possible so others can use it. You don’t want to be wrong by publishing prematurely, but that I think would be a way to motivate people to be more cooperative and communicative.

Advertisement