I’m back in El Salvador for the first time in thirty years, and I don’t recognize a thing. There are smooth highways from the airport up to San Salvador, the capital, and even at this late hour, along the stretch of dunes dividing the road from the Pacific Ocean, there are cheerful stands at which customers have parked to buy coconuts and típico foods. But I remember a pitted two-lane road, a merciless sun that picked out every detail on the taut skin of corpses, a hole in the sandy ground, the glaring news that four women from the United States, three of them nuns, had just been unearthed from that shallow pit.

“Is there a monument or a sign marking where the four Americanas were killed during the war?” I ask the driver of the hotel van.

“Yes, up in the university, the UCA, where they died.”

“No, those were the six Jesuit priests, years later, in San Salvador. I mean the nuns, in 1980, here.”

“Oh,” he replies. “I don’t remember.”

That event, the rape and murder of four religious workers on their way from the airport up to the city, was no doubt memorable to people like Robert White, the US ambassador in El Salvador during the last year of the Carter administration. He stood grimly at the funeral the next day, looking like another potential target of a putschist right-wing junta that had gone rogue. Already that year, Óscar Arnulfo Romero, the fearless archbishop of San Salvador, had been assassinated—to loud rejoicing by a ruling class that used to call him “Beezelbub.” Weeks after his murder, orchestrated in the darkest back channels of the regime by the notorious ideologue Roberto D’Aubuisson, the Reagan administration cranked up its military involvement in El Salvador, and dedicated billions of dollars to the junta’s fight against an insurgent coalition of guerrillas—Marxist radicals grouped under the umbrella name of Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN).

The twelve-year-long war would leave as many as 70,000 people dead by its end, but it started before more than half of all Salvadorans alive today were even born, and ended nearly twenty years ago. Why should a young van driver remember? And yet, the El Salvador of today, riddled by worse violence than at any point since the early years of the war, linked inseparably to the United States by an immigrant stream that started during the conflict, haunted always by the memory of the assassin Roberto D’Aubuisson, who went on to found the party that ruled his country uninterruptedly until the most recent election in 2009, is inconceivable without the years of bloodshed.

Salvadorans like to say that if someone bothered to iron their country it would actually be large. But it is tiny, and wrinkled, the lava of long-exhausted volcanoes furrowing and bending the landscape this way and that. San Salvador sits in a valley at the foot of a volcano, and guessing wildly one could say that it now has as many shopping malls as, say, Fort Lauderdale, and plazas and traffic roundabouts too, and tranquil neighborhoods with security guards on every block. It is very green, and even the slums creeping up the hills on the outskirts of the city seem lush to those used to more urban kinds of poverty.

On the very flank of the San Salvador volcano sits the town of Mejicanos, famous for its combativeness during the war. A long narrow street climbs up from it and then winds down and around the sides of a narrow canyon. Following it as it plunges along, one can see that the leafy shadows are dotted thickly with makeshift houses and shacks. Here and there, a knot of skinny men huddle around what looks like a crack pipe, but otherwise the street is silent and empty.

The neighborhood and the road are both called Montreal, and they are notorious. Last year a Montreal public transport bus making the trip to the center of Mejicanos was set on fire as it reached the Mejicanos market. Seventeen people burned to death. The toll included an eighteen-month-old child, but at least a few of the dead are said to have been members of one of the warring maras, ferocious gangs that are El Salvador’s own contribution to the drug trade and the world of transnational crime in which it takes place. Children of the war and the United States in more ways than one, they are responsible for most of the harrowing violence of today. They first began to attract public notice some twenty years ago, when what used to be a furious open conflict gave way to an ever- growing, pervasive sense of menace.

Advertisement

Around that time, Marisa D’Aubuisson de Martínez, sister of Roberto D’Aubuisson, decided to create a project for market women and their youngest children in a neighborhood like Mejicanos. Marisa’s forceful personality and easy laugh are in contrast to the will-o’-the-wisp, mesmerizing quality of her brother, as are her politics: she is a lifelong Catholic activist, a follower of the fearless archbishop her brother murdered. Roberto, who was to die of throat cancer in 1992, moved into electoral politics in the 1980s. As the war wrapped up, Marisa, too, changed, moving away from world-changing utopian dreams in order to focus on more attainable projects. I talked to her one day in the sunny, plain office where she works.

“At that time international aid went largely to macroprojects, but I started to write up something very small,” Marisa said. With international money, she founded an organization called Centros Infantiles de Desarrollo (CINDE) to provide day care for babies and toddlers, primarily for the children of women who make their living selling in the marketplace. Now there are three such centers, including one in Mejicanos, to which preschool and kindergarten facilities were eventually added.1 A few years ago CINDE created a program known as “school reinforcement,” in which older children can do their homework in safe surroundings and with adult guidance. One of them is in Montreal, and it is one of the few places in that neighborhood where outsiders can feel welcome and safe from the maras.

The after-school center is just an open-air hangar attached to two makeshift rooms that are rarely used, because they get oven-hot. On the breezy afternoon when I arrived the children were outside, enjoying an uproarious play break, but when the teacher in charge blew a whistle they returned at once to the open-air work tables and applied themselves to their homework almost voraciously. Everyone there, from the teachers to the volunteer monitors, seemed nearly feverish in their involvement. I interrupted the schoolwork of the older girls—who had ambitious English names like Jennifer and Natalie—to ask one if she came here to learn or to have fun, and she replied instantly and seriously, “I learn and I have fun.” Her grades had improved, up from Cs and Ds the previous year to a steady B average, but she was struggling, she said, with her least favorite subject, math.

Perhaps the general enthusiasm was due to the last-chance quality of the center itself. During a play break I watched a beautiful young girl kick a soccer ball around with her playmates as if she were still a child, but she was tall for her age and already nubile, and I felt almost sick with fear for her, having heard over and over that mareros—gang members—routinely force young girls in their territory into sexual service, a duty that often begins with collective rape.2 Or, on visita íntima day, which throughout Latin America is nominally the day when wives are allowed privacy with their jailed husbands or established partners, older girls may be sent as “wives” to the prisons where gang members are serving sentences. No one knows exactly how often the visita íntima may take place in Salvadoran prisons. As one friend pointed out, anyone who is admitted to some of the more notorious jails has access to the visita íntima rooms. Parents desperate to keep their daughters away from any sort of contact with the maras send them to the countryside to be raised by relatives, but not everyone has rural cousins or parents, and the barrio of Montreal and its dangers were this girl’s unavoidable circumstance.

As it is for the boys. “We have a boy who comes here all the time who is incredibly bright, really special,” one of the teachers told me in a low voice. “But he’s just a step away from joining the maras. He’s so little! Just a muchachito. We’ve talked to him about it, we try not to gloss over reality here, but he’s ready to go. We won’t be able to keep him away.”

I discovered some of the more immediate rewards available to boys who join the maras in the Mejicanos market, downhill again from Montreal. There, the market women, who have no problem at all with math, explained their lives to me in numbers: they pay the municipality thirty-five cents daily rent per each 1.5 linear meters their stands occupy.3 They spend fifty cents in bus fare to get to and from home, multiplied by the number of school-age children. Four dollars worth of produce purchased wholesale plus three dollars to ferry the merchandise back to their stands. The day’s earnings minus four dollars for the next day’s purchases, minus bus fares and taxis, leaves three, on a good day four, dollars to buy food for the family.

Advertisement

Then there is la renta, the daily extortion fee charged by mareros, but no one would do that math for me. Whether the renta around the market is charged by members of the Mara Salvatrucha—also known as the MS-13—gang or by the increasingly powerful rival group, the Barrio 18, was also left unclear. Several minors who belonged to the Barrio 18 were tried and sentenced for setting fire to the bus, but still no one I met, not even the teachers at the CINDE preschool center, was willing to talk about the incident.

I was chatting one afternoon with a particularly lively woman—let’s call her María—who started to tell me how CINDE and the microloan program it manages had changed her life, because she now had a cart in which to trundle her wares back and forth, when two boys who looked to be around fifteen years old arrived at her stand. She cut the conversation short as the kids selected some of her wares and left without any money changing hands. Maria’s eyes flickered with terror when I asked her if she was being renteada, or extorted, by the mareros. “Not really, not really,” she whispered, looking at me pleadingly. “They don’t ask me for money. Not yet. Just…little gifts.”

“We don’t rentear,” José Cruz declaimed loudly, as if for the world. “That is an invention of the press.” He has a great speaking voice, Chinese eyes above high cheekbones, none of the mareros’ trademark face tattoos, a lithe body, and a fantastically authoritative manner. “How are you doing?” he boomed as he walked into the prison visitors’ room, extending a wrist-cuffed hand, and never stopped lecturing from that point on. After our conversation a prison guard came up and, while one of his mates looked on, whispered that as a leader of the Barrio 18 gang Cruz was the de facto head of the penitentiary. It was Cruz, the guard said, who decided who gives press interviews (he did); which prison guards are allowed into the cell area where forty-five to fifty prisoners are confined every night in cells six by six meters large; and who gets punished.

He was very focused: at age twenty-nine he had already served seven years of his homicide sentence and had fifteen left to go, and he wanted to get out on time and alive. “I am a rehabilitable prisoner,” he informed me. He keeps his temper. At night, I heard, he retired early (I assumed he had larger headquarters than most) and slept soundly. After our conversation I was told that under the do-rag, or bandana, that imprisoned gang members wear he did, in fact, have tattoos—two eyes on the back of his head that allow him, he was not the only one to believe, to see his enemies at all times. He had been interviewed, he boasted, by French, Dutch, German, American journalists, you name it, and now he was trying to catch me with his rhetoric—we are victims of society, the rich get richer and the poor get poorer—but nothing he had to say was arresting as his physical presence, or the information whispered by the guard, but widely known outside the prison, that beatings and executions by knifing or beating were a fact of life in the penitentiary of Quezaltepeque.

Unlike the market women in Mejicanos, the guard had no particular reason not to talk: everyone knows that the prison system is bankrupt, and that it is impossible to control a detention system in which prisoners—nearly half of them accused or convicted killers—are stuffed into cells like industrial livestock. In El Salvador there are sixty-five homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, which is more than triple the current rate in Mexico, and significantly higher than the yearly death toll in the second half of the war. In a total prison population of 25,000, a third have never been sentenced. Overcrowding is so extreme that the prison system this year refused to take in more inmates. New detainees are being kept in police holding pens, but given the crime rate and the number of arrests the pens quickly become just as crowded.4

There have been riots and also peaceful strikes by prisoners demanding better conditions, but the men are not high on anyone’s list of priorities. It’s just one of the many catastrophes in El Salvador, where, twenty years after the war that was supposed to save the country—from capitalism or from communism, depending on which side you were on—there are half a million single parents, mostly women, trying to bring up their children safely. The government is bankrupt, the poverty rate is 38 percent, and the economy, which rose slightly from a negative growth rate of–2 percent in 2008 thanks only to an increase in the price of coffee, seems paralyzed.

It would be easy to lay the blame for this social and economic disaster exclusively at the feet of the party founded by Roberto D’Aubuisson—the Nationalist Republican Alliance, or ARENA, by its Spanish initials—which governed the country with evident if not single-minded interest in the well-being of the wealthy for twenty years after the peace accords were signed in 1992. (In 2009, Mauricio Funes, the candidate of the party founded by the former guerrillas, the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, or FMLN, won the presidency.) But there is also the enormous fact of the war itself: the demolished roads and other infrastructure, the collapse of rural society, the rise of urban slums peopled by campesinos fleeing those remote areas of the country that were the war’s principal staging ground, the systematic practice of ruthlessness, the drastic increase in single-parent families, the loss of an educated elite, the huge stockpile of leftover weapons no one kept track of. None of this, however, adds up to a complete or satisfactory explanation for the proliferation of the maras, currently estimated to number some 25,000 members at large, with another 9,000 in prison.

The phenomenon started in Los Angeles, where the children of immigrants who had fled the war had parents no one looked up to and were bombarded with ads for consumer goods they couldn’t have. They grew up in bad neighborhoods and inherited someone else’s enemies and turf wars. Among the second-generation Salvadorans in Los Angeles a significant number ended up creating their own groups to confront the Mexican and Afro-American gangs in whose neighborhoods their parents had settled. Of the two groups currently taking over just about every poor neighborhood in El Salvador, the Barrio 18 gang take their name from the 18th Street gang in Los Angeles, whose members number in the thousands. As for the Mara Salvatrucha, who started it all, the only part of their name everyone agrees on is that “Salva” must stand for Salvadoran.

As US immigration policy has focused on deporting the greatest possible number of undocumented migrants, no matter what their situation, a great many Salvadoran deportees, some of whom grew up in the United States and hardly speak Spanish, have found themselves back in their country of birth. A number of these unwilling returnees are mareros, who either join the local branch of their organization or try to flee back home (that is, to the United States), joining a migrant trail across Mexico used by hundreds of thousands of would-be US immigrants every year. Along the way, the mareros are often recruited by Mexican drug traffickers, who have developed highly lucrative sidelines in white slavery, child prostitution, and migrant extortion. Assault, robbery, and rape are now an expected part of the migrant journey through Mexico.

The most unlucky travelers are kidnapped in Mexico and held for ransom, usually between five hundred and two thousand dollars. If relatives back home cannot come up with the money quickly enough, the kidnap victims are killed. According to Mexico’s National Commission on Human Rights, 11,000 migrants were kidnapped in the first six months of 2010. There are no statistics on the total number of dead, but we know that in August last year seventy-two migrants were kidnapped and killed in a single incident. Six months later another 195 bodies were unearthed in the same municipal district. Mareros were probably among the assassins.

Howard Cotto, subdirector of investigations for the National Civil Police, has been learning about the maras for years. He is the trim, articulate product of the peace accords signed between the ARENA wartime government and the FMLN guerrillas, which included a UN-mandated restructuring of the various murderous police corps into a single force that integrated and trained members of both parties to the war. Another police commander, Jaime Granados, laughingly described the resulting National Civilian Police to me as the homely child no one wants, largely due to its efforts at neutrality. “We’re good police, very good,” he said. “But nobody is on our side.” The police are underfinanced and underequipped (there is one forensic expert for the whole country) and corruption is spreading, but they have managed to retain pockets of efficiency and professionalism, and the international diplomas and certificates that line the wall of Howard Cotto’s office—one is from the FBI—are signs of the commander’s prestige.

Cotto estimates that the gang’s support community in the barrios numbers perhaps eighty or ninety thousand, which together with the number of active and imprisoned mareros add up to about 1.5 percent of El Salvador’s population. Although the maras are on the retail end of the illegal drug trade in El Salvador, he does not attribute their growth to the drug-trafficking bonanza in Central America, now that the region has become the principal corridor for moving South American drugs to North America. “The gangs are clearly a part of organized crime, as are the traffickers of drugs and arms and stolen cars and so forth,” Cotto told me one morning in his sparsely furnished office. “But traffickers build hierarchical organizations around specific interests—white slavery, smuggling, drugs—and the traders lure people in on the basis of that [business]. The gangs do the opposite: they recruit from the bottom up.”

The gangs distribute drugs in the barrio while casting themselves as its defenders, Cotto said.

But in reality, they don’t defend the barrio; they terrorize it. The barrio is the territory where they extort, distribute drugs, kill, and make money. But they don’t live with a lot of luxury; they’re not narcos. Their origins are in the community, and what they fear more than death itself is losing their authority there, because the moment they do that, they’re dead. But it’s an excellent way of living comfortably and giving money to a lot of people; their strength lies in not breaking that chain of money distribution. That’s how they can say [to their underlings], “fight for me.”

Cotto chatted easily under a wintry blast of air conditioning. “[A marero’s] life is very short,” he continued.

They get sentenced to thirty years in no time. But in this country, as they see it, they have two choices: you can be a loser and keep on studying, and let’s see if you can find a job once you’ve graduated, or you can be a powerful man by the time you’re fourteen or seventeen. You can give orders, be in charge of distributing drugs in the neighborhood. You won’t have to give your elders any respect, you’ll be the one who can say to a neighbor, “You’re going to leave this barrio this minute,” and then take over his house. You’ll be able to say to that girl you like and who doesn’t like you, “You know what, whether you like it or not you’re going to be mine, or whoever else’s I decide.”

Cotto has seen a lot of corpses by now: beheaded, dismembered, set on fire. (It is said that the first thing a new marero must do, no matter how young, is arbitrarily kill someone. After that, they’re ready for reprogramming.) But the most upsetting murder scene he ever arrived at was in a mara stronghold, in one of the collective homes the kids call casa destroyer. “I was nonplussed,” he says. “We walked into the house and all the kids were there, in a circle. And there was the dead person. He’d been dead a few hours already, but they hadn’t [disposed of him]. They were just sitting around the corpse, chatting and taking it easy.”

Alexis Ramírez, who joined the maras when he was fifteen, doesn’t look like he could kill people thoughtlessly, although he is serving fifty years for homicide and has forty-eight left to go. He has dark skin, full lips that look sculpted, big black eyes, and looks much younger than his twenty-nine years. I asked him if, when he was free, it hadn’t been dangerous for him to walk down the street covered in tattoos, and he gave a sideways smile. “If you know how to walk it’s not. From corner to corner…that’s how I’ve been all over El Salvador.” And he made a ducking, aw-shucks movement that made me see how he could, in fact, slip and smile his way around many obstacles.

He came, he said, from a nice family; his father, an evangelical, “was always involved in matters of the church,” while his mother “for approximately fifteen years has been persevering in the things of God.” His brothers work in a carpentry shop. His father-in-law recently managed to smuggle Alexis’s wife out of the country, presumably in order to get her away from Alexis’s influence, and the couple lost custody of their two children—now aged five and nine—who are in the care of their grandparents.

He was still in school when he decided to join the maras. “I saw the tattoos [of the mareros in his neighborhood]. I saw the way they behaved toward each other,” he said. “In my neighborhood they didn’t steal from people; they took care of them. I liked all that.”

He had, I pointed out, a fairly dismal life. Didn’t he regret the decision to join?

“When we took the option of being what we are,” he answered, “we knew there was no turning back.” I tried, unsuccessfully, to figure out if that ducking, swaying thing he did was an authentic remnant of what had once been a whole and gentle person, or an ingratiating trick that a thoughtless killer kept stored among his array of weapons.

José Eduardo Villalta, twenty-four, has the word “eighteen,” as in Barrio 18, tattooed in French and English on his arms and fingers, and in Latin numerals and various other codes wherever else a tattoo can fit. He has no charm, but in the course of our conversation it came out that he was originally from the countryside, and that his mother visits him regularly. I asked him to describe how one sets up a milpa, or corn field, and as he was going through the procedures—cutting down, burning, overturning, hoeing, planting—I had a momentary vision of a youth breathing free air. He has most of a fifty-year sentence still ahead of him, and I asked him if he didn’t find that depressing.

“No,” he said firmly. “I feel at ease here. This is my home.”

—October 12, 2011

Research support for this article was provided by The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute.

This Issue

November 10, 2011

Our ‘Broken System’ of Criminal Justice

The Real Deng

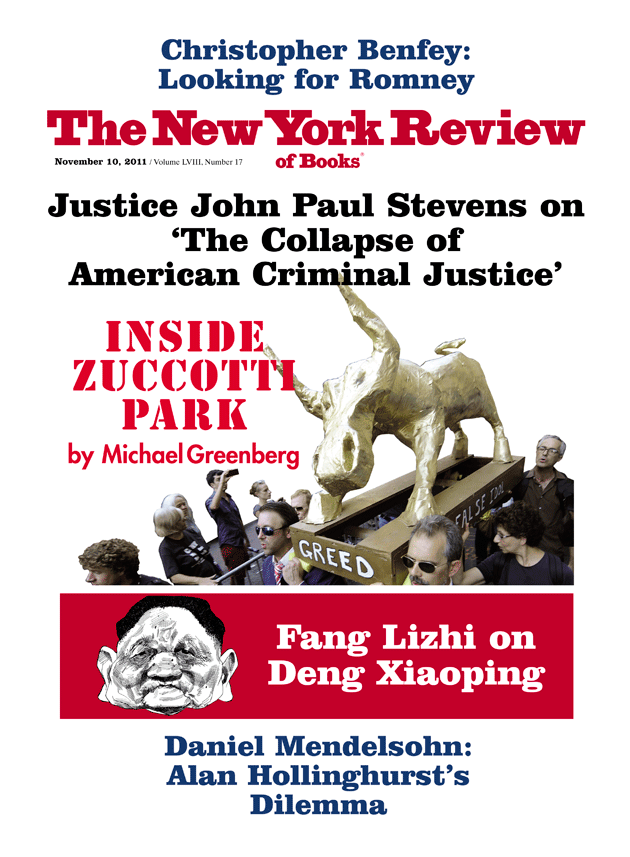

In Zuccotti Park

-

1

The day care centers were canceled this year for lack of funds, leaving only the kindergarten and preschool programs. ↩

-

2

A chilling account of one such rape was published in July by the remarkable Salvadoran online daily El Faro: see Roberto Valencia, “Yo Violada,” available at www.salanegra.elfaro.net/es/201107/cronicas/4922/. ↩

-

3

El Salvador’s official currency is the US dollar. ↩

-

4

Not long after my visit, the head of the penitentiary system dismissed and replaced all the Quezaltepeque prison’s custodians. ↩