The title of Hillary Clinton’s memoir of her unsuccessful campaign for the presidency, What Happened, has no question mark at the end, although many people around the world might reflexively add one. Clinton’s defeat surprised—stunned—many, including, as is clear from her recollections, Clinton herself. The majority of polls of the likely electorate indicated that she was headed for a nearly certain win, although her prolonged struggle for the Democratic nomination against a wild-haired, septuagenarian socialist from Vermont was a blinking sign of danger ahead. A significant number of voters were in no mood to play it safe, and the safe choice was what Clinton far too confidently offered in both the primaries and the general election.

It was not only the polls that led observers astray; their instincts did as well. Many, within and outside the country, had trouble imagining that the American people would elect to the most important position in the land, perhaps in the world, a man who had never been elected or appointed to public office, nor sworn an oath of allegiance to the United States as a member of the armed services, nor shown any serious interest in public service. From the time candidates can be said to have openly campaigned for the office, those aspiring to the presidency have touted their possession of these extraconstitutionally mandated qualifications, and all presidents before Donald Trump had at least one of them. They are “extraconstitutional” because none is a requirement for the presidency. Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution lists only three qualifications relevant to modern times: that the president be a “natural born citizen,” at least thirty-five years old, and a resident “within the United States” for fourteen years.

The historian Jack Rakove observed that the American presidency “posed the single most perplexing problem of institutional design” that the framers faced. “The task of establishing a national executive on republican principles,” Rakove says, “puzzled” them.1 What kind of executive would be suitable in post-Revolutionary America? What type and amount of power should the Constitution give to a person who, in the absence of a vigilant citizenry, might begin to act like a king? And what if the people came to love the president so much that they did not mind—perhaps even welcomed—deviations from republican principles?

Despite these reservations, it was understood by the framers that the president had to be a powerful figure who could symbolize the nation. Just what that meant has been contested. Rakove’s notion that the substance of the presidency had to be “discovered” and “invented” seems exactly right; and the process of discovery has continued, with varying results, over the years.

While adhering to the Constitution’s minimal qualifications, American voters have always had the ability to choose a president who did not fit the norms as they have evolved. They did that in spectacular fashion when they elected a black man, Barack Obama, to the presidency in 2008. It had long been assumed by most Americans that being white was a requirement for the highest office in the land. It would likely never have occurred to the men who wrote the Constitution that they had to specify that the person at the head of the government of the United States—and the symbol of the nation—was to be white. This would have been a deeply felt cultural understanding, and cultural understandings can have significantly more force and staying power than rules of law.

The framers also likely never thought to state explicitly that the president had to be a man. As former British subjects, they knew it was possible for a woman to head the nation as queen, when the king had no male heirs. That did not happen very often, however, and the American Revolution got rid of monarchy and the possibility of queens. Under the new Constitution, presidents would be elected by qualified voters, who would almost invariably be male. For a brief period in the early American republic, New Jersey, in the words of the historian Jan Ellen Lewis, made the “lonely” decision to allow single, propertied women to vote. It was the sole state in which this happened.2

Even if there was a narrow and short-lived precedent for women voting, there is no evidence of enthusiasm for women holding office, appointive or elective. Indeed, when Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin noticed a shortage of individuals qualified to hold office during the second Jefferson administration, he suggested that the president consider hiring women. President Jefferson, taking his role as the symbol of the nation to heart, replied, “The appointment of a woman to office is an innovation for which the public is not prepared, nor am I.”

Advertisement

As things turned out, cultural understandings about the electoral process in relation to gender were more powerful than understandings about it in relation to race. Much to the chagrin—rage, actually—of many white female abolitionists and women’s rights activists, the Fifteenth Amendment gave newly freed black men the right to vote in 1870. Although cultural understandings that promoted white supremacy interfered with the law for decades (and continue today in the form of voter suppression), black men voted and held office during Reconstruction—Mississippi had two black senators, Louisiana for a short time had a black governor, and “an estimated 2,000 black men served in some kind of elective office during that era.”3

It was not until 1916 that the first woman, Jeannette Rankin, was elected to national office. Rankin was elected to Congress from Montana. Women in Wyoming were given the right to vote in 1869. But women of all races had to wait until the twentieth century, with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, for the constitutional right to vote. The question of who would go first in the march of national electoral progress—black men or white women—was asked again during the 2008 presidential primary contest between Obama and Clinton. The answer was the same as it had been in the 1860s.

“This is my story of what happened,” Clinton writes in the book’s first line, acknowledging that her account of the 2016 election will inevitably be subjective. What Happened is her third memoir, and with it she defies the conventional wisdom that would suggest waiting at least a few years after important events to reflect upon them, with an eye toward gaining the perspective that distance is said to bring. Clinton’s choice to write this book now, however, seems fitting because nearly everything about the election of 2016 was unconventional. It brought forth the first woman to mount a serious run for the presidency, a rival candidate strange for the reasons listed above (and many more not listed), and the first inkling that a new form of technology-based espionage had been deployed in an effort to shape the outcome of a US election. Historians can benefit from Clinton’s near-contemporaneous consideration of each of these issues. They will likely find her quick first draft engaging (when she does not lapse into campaign-speak), witty, and useful, even as they take note of her natural self-interest in writing about these matters.

What Happened is necessarily about gender. Clinton’s femaleness mattered so much to her candidacy—how she ran, what she could and could not do, the expectations people had of her, and the expectations she had for herself—that the subject suffuses even the chapters in which gender is not explicitly addressed. It could hardly be otherwise, given the history of women and electoral politics. In “On Being a Woman in Politics,” the first chapter of “Sisterhood,” one of the book’s six thematic sections, Clinton vents. “In these pages, I put to paper years’ worth of frustration about the tightrope that I and other women have had to walk in order to participate in American politics.” There was a basic problem of which she was well aware:

In short, it’s not customary to have women lead or even to engage in the rough-and-tumble of politics. It’s not normal—not yet. So when it happens, it often doesn’t feel quite right. That may sound vague, but it’s potent. People cast their votes based on feelings like that all the time.

Becoming the president of the United States, Clinton believes, is a particularly difficult goal for a woman to achieve. “Women leaders around the world,” she observes, “tend to rise higher in parliamentary systems, rather than presidential ones like ours.” She may have been influenced by the political scientist Farida Jalalzai, whom the Atlantic Monthly commentator Uri Friedman quoted when he wrote, in a postmortem of Clinton’s campaign, that women “are more likely to serve as prime ministers than as presidents, perhaps because in parliamentary systems women can ‘bypass a potentially biased general public and be chosen by the party.’” Friedman goes on to suggest that “to win a national vote in a presidential system, women must contend more directly, and on a larger scale, with sexism and stereotypes.”4 It should not surprise us that requiring candidates to run as potential symbols of the nation would place women at a disadvantage.

The person at the head of the ticket undoubtedly matters in both parliamentary and presidential systems. But the person matters more in a system that encourages voters to fixate on their instinctive responses to a candidate’s personality, rather than on support for a party and its overall policies. This effect is amplified by the media’s tendency to concentrate on personalities over policies, aping the convention that governs Hollywood’s treatment of celebrities: a star’s ineffable qualities are more important than his or her competence as an actor. In such a system, the candidate must be acceptable—likable—across a wide swath of the voting population,5 and capable, in Clinton’s words, of “speaking to large crowds, looking commanding on camera, dominating in debates, galvanizing mass movements, and in America, raising a billion dollars.” It is an enterprise based on seduction.

Advertisement

Women can obviously do these things, but how are they received when they do them effectively? A woman operating in the US’s political system, as Jalalzai suggests, will necessarily encounter age-old understandings about femininity and masculinity that have remained in place to a greater extent than many care to acknowledge, and that remain undisturbed by firsthand experiences with the candidate. On the other hand, Clinton says, in parliamentary systems

prime ministers are chosen by their colleagues—people they’ve worked with day in and day out, who’ve seen firsthand their talents and competence. It’s a system designed to reward women’s skill at building relationships, which requires emotional labor.

One suspects that Clinton is right in suggesting that in another place, in another system, her qualities would have made her the head of her party and, ultimately, prime minister.

Even though it was not the only reason she did not become president—the media’s excessive focus on her e-mails and James Comey’s bizarre and devastating actions in the week before the election both did their part—it matters greatly to considerations of Clinton’s loss in 2016 that the United States has never elected a woman president, and it is naive to think otherwise. History and culture tell us why no woman has ever occupied this office, and why putting a woman in the country’s ultimate position of power might have been difficult for a good number of men and women voters to do—especially for many whites after the culture-shaking experience of having had a black president. It is not just the presidency. According to statistics compiled by the Inter-Parliamentary Union in 2017, the United States “lags far behind many countries” in women’s overall participation in the national government, ranking 101st out of 193.

The US’s lackluster record in electing women to national public office must be acknowledged, not just for what it says about Clinton, but for what it says about the likely experiences and fortunes of women who run for president in the future. Even had Clinton won it would be appropriate to pay attention to her treatment as a female candidate. Talking about the part gender played in her defeat is not to make excuses, as has been charged whenever the harmful double standards applied to her are pointed out. And it is far too easy to say that Clinton was simply the “wrong” woman, a tactic often employed to short-circuit discussions about gender and the election.

There is no reason to doubt that any woman who had been the first to run for president with the backing of a major party would have encountered some of the gender-based scrutiny Clinton faced, and that female candidates in the immediate future will shoulder some of it as well. The journalist Ezra Klein has observed that Elizabeth Warren, a politician very different from Clinton in style, temperament, and political orientation, has begun to receive the same kind of gender-based treatment that Clinton faced. “We routinely underestimate,” he wrote this past fall,

what it means that our political system has been constructed and interpreted by men, that our expectations for politicians have been set by generations of male politicians and shaped by generations of male pundits.6

Another journalist, Jill Filipovic, even more adamantly linked the recent allegations of sexual misconduct by various media figures to the presidential campaign:

Many of the male journalists who stand accused of sexual harassment were on the forefront of covering the presidential race between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. Matt Lauer interviewed Mrs. Clinton and Mr. Trump in an official “commander-in-chief forum” for NBC. He notoriously peppered and interrupted Mrs. Clinton with cold, aggressive, condescending questions hyper-focused on her emails, only to pitch softballs at Mr. Trump and treat him with gentle collegiality a half-hour later. Mark Halperin and Charlie Rose set much of the televised political discourse on the race, interviewing other pundits, opining themselves and obsessing over the electoral play-by-play. Mr. Rose, after the election, took a tone similar to Mr. Lauer’s with Mrs. Clinton—talking down to her, interrupting her, portraying her as untrustworthy. Mr. Halperin was a harsh critic of Mrs. Clinton, painting her as ruthless and corrupt, while going surprisingly easy on Mr. Trump. The reporter Glenn Thrush, currently on leave from The New York Times because of sexual harassment allegations, covered Mrs. Clinton’s 2008 campaign when he was at Newsday and continued to write about her over the next eight years for Politico.7

These revelations, which also reignited stories of sexual misconduct by Bill Clinton and by the current president, have made it clear that gender-based negative attitudes and actions do not just affect the individual women at whom they are aimed; they impede the progress of women overall. The misogyny of major participants who helped shape the 2016 election must be a part of any serious historical analysis of what happened in the campaign.

Other factors—her name, her personal history, and her campaign strategy—also worked against Clinton. Voters had every right to chafe at the notion that in a nation so large and blessed with talent as the United States, two of the people who emerged as likely standard-bearers for each party were named Bush and Clinton. Jeb Bush, scion of the Bush dynasty, was quickly dispatched and Hillary Clinton was left to bear the brunt of the public’s hostility toward establishment candidates. She had served four years in the Obama administration in the high-profile position of secretary of state and been subjected to harsh criticism for foreign policy blunders, both real and imagined. Many disaffected Democrats felt that she was too close to Wall Street because she took corporate money and gave speeches before financial institutions, some of whose members now run the financial system of the United States. In the eyes of a crucial number of voters, Clinton symbolized a hated neoliberal status quo.

The status quo for many Americans—leaving aside those who the journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates persuasively argues wanted to vote for a white man to uphold white supremacy8—was one of economic stagnation, generalized anxiety about the future, and anguish over the loss of young people to opioid addiction in depressed areas of the nation. Bernie Sanders, whom Clinton describes as “outraged about everything,” and Donald Trump, who knew how to develop themes on social media better than all of his competitors, appealed to people who believed that the country’s future depended on sharply altering the course of history.

And then there was Clinton’s image of herself as the meticulous, responsible choice. “Sweating the Details,” the title of one chapter, is important in politics, but an inspirational and easily digestible story is more effective in a campaign than seeking to impress with facts and details, as much as we might wish otherwise. As Mario Cuomo famously said, politicians “campaign in poetry” but “govern in prose.” Only if their poetry is good enough will they be allowed to govern.

Perhaps the most revealing passage in What Happened is Clinton’s statement that she has “always identified with the older brother” in the parable of the Prodigal Son, an admission that highlights both her Methodism, something she played down during most of her political career, and her sense of who she is and how she has been seen:

How grating it must have been to see his wayward sibling welcomed back as if nothing had happened. It must have felt as if all his years of hard work and dutiful care meant nothing at all.

Indeed. How grating it must have been after all of her hard work for the Democratic Party, including prodigious fund-raising, to be challenged by Sanders, who after decades in politics joined the party only during the primaries. How grating it must have been, after her dutiful care and attention to policy questions, to lose the presidency to Trump, who disdained discussing policy at any level other than the most general. Dutifulness faltered in the face of passion:

In my more introspective moments, I do recognize that my campaign in 2016 lacked the sense of urgency and passion that I remember from ’92. Back then, we were on a mission to revitalize the Democratic Party and bring our country back from twelve years of trickle-down economics that exploded the deficit, hurt the middle class, and increased poverty. In 2016, we were seeking to build on eight years of progress. For a change-hungry electorate, it was a harder sell. More hopeful voters bought it; more pessimistic voters didn’t.

Finally, there is the schizophrenic response to Clinton. Regularly hailed as one of the most admired women in the world, she has also been the object of an intense, unremitting hatred that, for some, appears to know no boundaries. She is said to have murdered someone—her husband’s deputy White House counsel, Vincent Foster—and ordered the executions of others. She has been pronounced “the Antichrist.” Clinton addresses both of these ways in which she has been viewed, and is clearly more perplexed by the hatred than the admiration. What person other than one in the grip of crippling self-doubt—which Clinton is definitely not—thinks herself or himself worthy of deep hatred?

One could have been implacably opposed to everything Clinton stands for and have worked overtime to ensure her defeat in this past election and in 2008 without actually hating her. Something more is clearly going on here, and it is not all about her shortcomings as a politician and a person. Can hating Hillary Clinton as a politician be separated from hating Hillary Clinton as a woman? More specifically, in how many minds were those thoughts separated during the 2016 election?

There is no question that a segment of the population, male and female, hates and disrespects women and finds it hard to take them seriously when they move outside of traditional roles. This is doubly true of women past a certain age, who are supposed to become invisible. And here was this woman, well past the age of visibility, insisting on being seen and heard! Journalists spoke of hating to hear the sound of her voice. Clinton notes this reaction to her use of the most primary means by which politicians communicate—speaking:

Historically, women haven’t been the ones writing the laws or leading the armies and navies. We’re not the ones up there behind the podium rallying crowds, uniting the country. It’s men who lead. It’s men who speak. It’s men who represent us to the world and even to ourselves.

That’s been the case for so long that it has infiltrated our deepest thoughts. I suspect that for many of us—more than we might think—it feels somehow off to picture a woman President sitting in the Oval Office or the Situation Room. It’s discordant to tune into a political rally and hear a woman’s voice booming (“screaming,” “screeching”) forth. Even the simple act of a woman standing up and speaking to a crowd is relatively new. Think about it: we know of only a handful of speeches by women before the latter half of the twentieth century, and those tend to be by women in extreme and desperate situations. Joan of Arc said a lot of interesting things before they burned her at the stake.9

One suspects that this kneejerk and, in most cases, unconscious animosity added an extra measure of feeling to whatever legitimate policy disputes many observers had with Clinton—hate topped off principled opposition. And this hate seemed to spread over the course of the campaign to voters and commentators who would not, perhaps, have come to hate Clinton on their own. Because human beings are social creatures, expressions of contempt are hard to contain in just one individual. People who do not feel it may try to understand why others have had such an extreme and personally debilitating response. Eventually, they may come to assume that the object of hatred must deserve it.

Clinton ends her memoir at the place where her public life began: Wellesley College, where she famously gave an address at her commencement in 1969. Listening to the 2017 Wellesley student speaker, Tala Nashawati, Clinton is captivated by the young woman’s comparison of herself and her classmates to “flawed emeralds” that are often “better than flawless ones” because their “flaws show authenticity and character.” Authenticity and character are two attributes that Clinton’s most ardent detractors insist she does not possess, defining her solely in terms of her flaws. Her joy at Nashawati’s reclamation of the word “flaw” is touching and instructive. After all this time, Clinton feels the need to make the case that she is, after all, a human being.

This Issue

February 8, 2018

To Be, or Not to Be

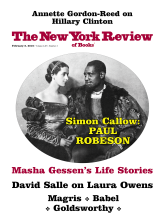

The Emperor Robeson

-

1

Jack N. Rakove, “The Political Presidency: Discovery and Invention,” in The Revolution of 1800: Democracy, Race, and the New Republic, edited by James J. Horn, Jan Ellen Lewis, and Peter S. Onuf (University Press of Virginia, 2002). ↩

-

2

Jan Ellen Lewis, “Rethinking Women’s Suffrage in New Jersey, 1776–1807,” Rutgers University Law Review, Vol. 63, No. 3 (Spring 2011), pp. 1017, 1018. ↩

-

3

Eric Foner, “Rooted in Reconstruction,” The Nation, November 3, 2008. ↩

-

4

Uri Friedman, “Why It’s So Hard for a Woman to Become President of the United States,” The Atlantic, November 12, 2016. ↩

-

5

Clinton won the popular vote by nearly three million; it was our creaky eighteenth-century constitutional structure that tripped her up. But the stubborn chosen narrative, set in stone back in the 1990s, was that, unlike her husband, Hillary Clinton was not that most prized thing in American politics: likable. ↩

-

6

Ezra Klein, “Political Journalism Has Been Profoundly Shaped by Men Like Leon Wieseltier and Mark Halperin and It Matters,” Vox, October 27, 2017. ↩

-

7

Jill Filipovic, “The Men Who Cost Clinton the Election,” The New York Times, December 1, 2017. Glenn Thrush has since been reinstated at the Times, but not on the White House beat. ↩

-

8

Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The First White President,” The Atlantic, October 2017. ↩

-

9

During her UK book tour, Clinton discussed the campaign in a public conversation with the historian Mary Beard, whose most recent book, Women and Power: A Manifesto (Liveright, 2017), discusses, among other things, the millennia-old hostility toward women speaking in public. See “Hillary Clinton Meets Mary Beard: ‘I Would Love to Have Told Trump: “Back Off, You Creep,”’” The Guardian, December 2, 2017. ↩