Wilton Barnhardt may not yet be a household name, but he is a fascinating writer, and Lookaway, Lookaway, his fourth novel, may be the one to get people’s attention. It certainly ought to be. Barnhardt is one of those writers who does not easily fit into the categories we’ve gotten used to. He is a male writer who writes, most often, about women. He’s been the director of the creative writing masters program at North Carolina State and has taught at numerous other colleges and universities, yet his work has none of the traits of the small, intense, overly worked products typical of so many MFA programs. He is a southerner who has not, until now, written about the South (his first novel, Emma Who Saved My Life, took place in New York City; the second, Gospel, rambled from Chicago to London to Ireland to Italy to Greece to Israel; the third, Show World, was set in Los Angeles).

Lookaway, Lookaway has the canny flair of the best contemporary novelists, but here it is put in the service not of stylish bravado but of the magnificent, obsessive reading experience of the loose, baggy monsters of the nineteenth century. The book is neither loose nor baggy—it is composed with great care and delicacy—but it has about it a span, a completeness, a fullness, and a richness that we associate with novels from that century.

An uncompromising satire of the nostalgic “legacy” of the South, the sentiment that causes states to fly the Confederate flag, this novel is also an emotional and layered reflection on a family. Barnhardt knows the eccentricity of the South and the way a culture can be twisted by its past, but more important for a novel that is more than a tract, he has a true understanding of the eccentricity of even the most conventional-seeming family. Like Trollope, the nineteenth-century male writer who best understood women, Barnhardt writes about women with comfortable familiarity. And like Trollope, who clearly was an inspiration, he knows the world is never free of politics. In this novel, Barnhardt approaches the worlds of politics, society, family life, sexual identity, and economic insecurity without naiveté, but without the knowing cynicism that is the mark of lesser satirical novels. His seriousness of purpose is joined to a joyous sense of absurdity, and the warmth and specificity of each of his southern ne’er-do-wells infuse this bright, insolent satire with both sweetness and sadness.

The two of Barnhardt’s earlier novels that I’ve read, Emma Who Saved My Life and Gospel, were beautifully written, both of them; they were, also, a bit loose and baggy in exactly the way this new novel is not. Emma had an appealing modesty and charm, but it was often asked to heft onto its shoulders a somewhat ill-fitting, weighty scheme: all of 1970s New York City with its period peculiarities of theater, art, real estate, and STDs. The story of a young actor who comes to make it in the Big Apple, the novel is a little too personal to be sweeping and a little too sweeping to be personal.

Gospel, Barnhardt’s second novel, is a far more ambitious book, breathtakingly ambitious, really—a tale of the possible discovery of an unknown manuscript, a first-century gospel written by the disciple Matthius, the hapless brother of the great Jewish historian Josephus, a manuscript that might historically, anyway, disprove the divinity of Jesus. There is intrigue, there are fragments of the manuscript itself, there is the delightfully droll voice of God, which pops up now and then to comment with benign exasperation on Barnhardt’s other, less omniscient characters. There are also footnotes, clusters of them, full of unexpected bits of scholarship, engaging martyrdoms, hagiographies, schisms, and general early church mayhem. But the ambition of the book breathes a little too hotly and the story, again, struggles to keep up with the profundity of its goals. Both of these books were impeccably researched and written with wit and intelligence. But somehow they did not quite live up to their own expectations. Their characters were simply not as interesting as the writing that described them.

In Lookaway, Lookaway, however, Barnhardt has found his people, wonderful, crackpot, exasperating people. He has given them a story seamlessly composed, emotionally textured, bitter, touching, and funny. It is a happy reminder of what an unlikely, endearing, and precious phenomenon the novel can still be. The momentum of the story (a superb, scandal-filled trajectory of comic tragedy) is so great, the prose so lucid and elegant, that it is only when you finish that you realize this has not been the straightforward tale you were sure you were caught up in, but a spiral of stories, a vortex of comic circles that swirl you down not to an Inferno, but instead back into your own American backyard, where Barnhardt sets you down, very gently, to feel a distinctly southern heat.

Advertisement

The Johnstons of Charlotte, North Carolina, are the subject of this family saga—their history and their deceptions. They are tastefully, hopelessly entwined in the southern past, it seems. Joseph Beauregard Johnston, descendant of Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston, once the golden darling of Duke University, ever since called Duke, became a flourishing lawyer in the 1980s with political ambition and possibility. But he has given it all up, given up every pursuit but an obsessive interest in the Civil War. For years now he has done nothing but collect what one aunt calls “Civil War bric-a-brac”: dueling pistols, maps, cannonballs, swords. His study smells “of an ever-welcoming past, of lost causes and unvanquished honor.” Every year, Duke plans and leads a reenactment of an 1864 battle, albeit a laughably meager and trivial one, known as the Skirmish at the Trestle. Duke plans to make the site of the Skirmish, such as it was, a memorial park to honor what his brother-in-law describes as “the zeroes of brave men who fought alongside the U.S. 21 Bypass.”

The novel begins with a sensuous moment suspended between the southern past and the future as Duke’s youngest daughter, Jerilyn, caresses her debutante gown, “a tulle cloud, something right out of an antebellum cotillion.” Even a young girl’s beginning, her debut, is mired in the past. But this novel is no nostalgic bodice ripper. Bodices are, indeed, ripped, and the book is exhilarating and suspenseful, but Lookaway, Lookaway, as the title implies, is at its heart a story about secrets and lies and the social, emotional, and even literary deformity that secrets and lies leave behind.

Jerilyn, cute and well brought up, hardworking at school, is headed for Chapel Hill where her ambition is to snag an eligible society boy via what she calls Operation Sorority. Her mother has forbidden sororities altogether; she will not have her daughter “waste thousands a semester inebriating yourself and abandoning your studies at Chapel Hill.”

But in this, her first act of rebellion, the obedient daughter is determined. “She would turn the page on decorum-blighted Jerilyn Johnston.” She not only joins a sorority, she joins the wildest, druggiest, sluttiest of them all, Sigma Kappa Nu. “The Sigma Kappa girls had morals that would shame a Babylonian in my day,” her mother tells her. “Their mothers were wild as hyenas, too.”

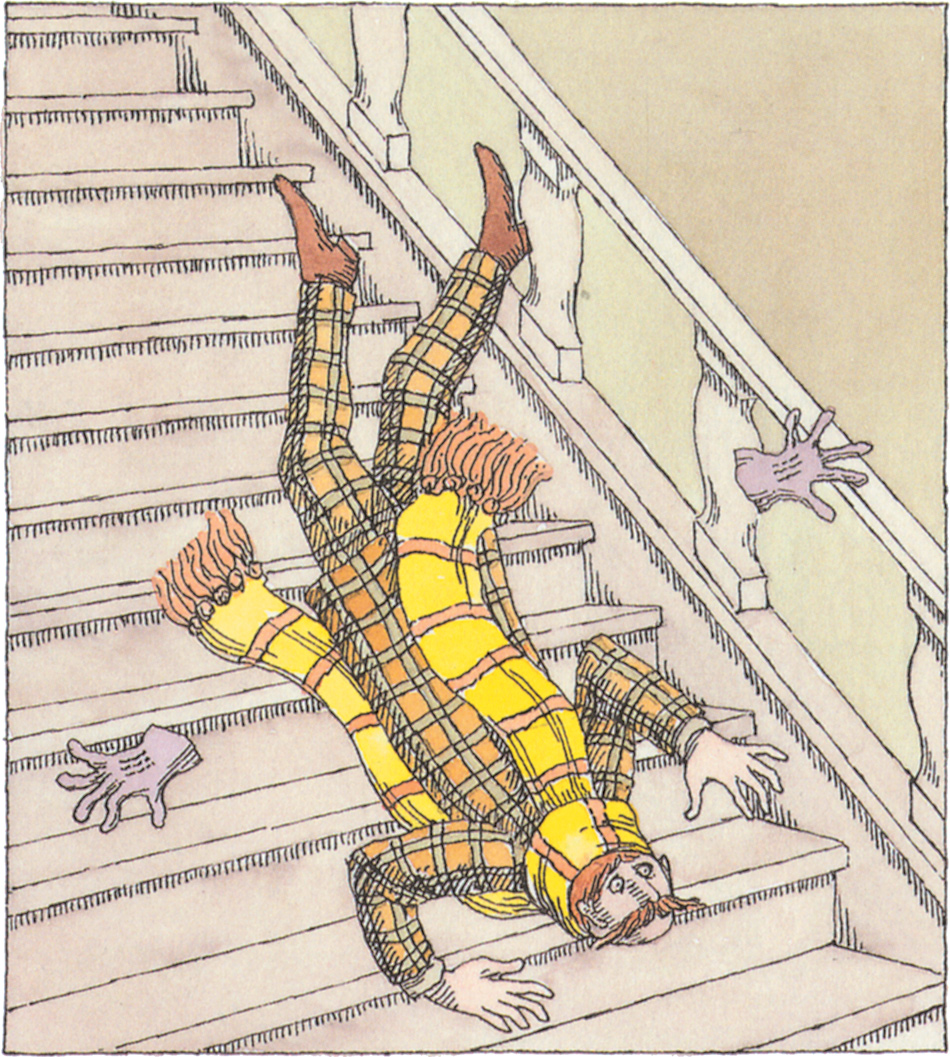

The description of Greek partying at Chapel Hill is intentionally over-familiar. There are sexually abused sheep, cocaine, crass boys and crass girls, bewildered innocents trying to keep up. Interspersed are quick satiric moments that flash, as disturbing and transient as distant lightning. Here is the plumber at the sorority house trying to explain the blocked pipes:

“You have to…” The man, who could be anybody’s grandfather, looked concerned, perhaps for the plumbing, not so much for the girls. “You have to… You have to chew your food, miss. Get the girls to digest their food. You can’t just swallow it for a little while and throw it up into the toilet.”

Or the girl who offers her father’s plastic surgery skills at a Sigma Kappa Nu discount:

“My dad can get rid of all of that upper-arm fat,” Georgina said…. “Not to mention up your cup size.”

“Puh-leeease tell me,” Cortney said, “that your own dad didn’t do your boob job.”

He did.

This is exactly the environment Jerilyn is searching for, the cliché sorority: she wants to “immerse herself in this too shallow pool,” and she soon has her chance—a drunken, coke-fueled frat party at which the Sigma Kappa Nus would “be in super-slut mode…and then get out at ‘maximum tease.’” Jerilyn’s experience is a little less nuanced: she is raped.

And we leave her, a hand across her mouth, a drunken frat boy “doing the thing she didn’t want him to do.” The next chapter moves abruptly to her Uncle Gaston. The switch, so emphatic, so clean, is almost as startling as the rape. This is not Jerilyn’s story, we realize, not hers alone. This is not just a college satire, but the story of an entire family, and now we meet the obese and bitter alcoholic uncle.

After two serious and critically acclaimed novels, Gaston Jarvis wrote a cheesy Civil War best seller whose heroine, Cordelia Florabloom, is now his nemesis. “His series was up to Book Number Eight, two decades from the first one, a span four times the length of the War Between the States itself.” Cordelia has added to his life an enormous fortune, a drinking problem, several hundred pounds of pale flesh, and a cult following of blue-haired matrons and tottering old men dressed in full Confederate regalia. Gaston thinks of himself, almost fondly, as a man of “excess, immoderation, petulance. He was especially good at petulance.”

Advertisement

Gaston met Duke in college and worshiped him. They became close friends, bonding on bourbon and dreams of the future. It was Gaston who introduced Duke to his future wife, Jerene Jarvis, Gaston’s sister.

Barnhardt tells each chapter from a different character’s point of view, and Jerene’s is Chapter Three, but she is there from the beginning. She is the smooth, taut comic thread that holds the book, and the family, together like a steel cable. Both Jerilyn and Gaston think about her as a pillar of propriety, but every time Jerene opens her mouth, we see she is much more: she is a splendid monstress. Her family sometimes wonders if she has a heart, but we see early on that it is Jerene who is the heart of this book. She is irresistible, like that emblematic southern female, Scarlett O’Hara, possessed of the same supremely selfish spirit that keeps up the spirits of those around her.

But where Scarlett was fire, Jerene is ice. Where Scarlett broke the rules, Jerene enforces them, down to the direction the stems of a bride’s flowers should face as she walks down the aisle. (“I’ve counted at least twenty breaches of tradition, and today’s lapses in good taste are…oh my land, without number, without number.”) What they have in common is a remarkable moral agility, a nimble pragmatism and unfettered ruthlessness on behalf of the family name. Rushing to her daughter’s side after the rape, Jerene asks what the boy’s father does for a living. When Jerilyn cannot answer—she barely knows the boy’s name—Jerene calmly advises her:

Darling, in the future, you may not invite to bed any young man about whom you do not know his father’s profession, his eventual means, his status in this world. That is a one-way ticket to the mobile-home park.

When Jerilyn feebly defends her sorority, her mother sets her straight:

Many of the girls here are whores. Their mothers were probably trash, too, whatever their pedigree. You can direct the men who can’t behave themselves to those girls who’ll spread their legs gladly. It hardly matters what they do, it only matters what you do…. Jeriflower, let me clarify your mission here at the University of North Carolina.

Jerilyn is to learn how to do something she enjoys until she finds a proper husband, then it will be time to trade on her “good looks and good name for an even better life than we have, darling. So your daughter can do as she pleases.”

In the meantime, though, there is this rape. Jerene blandly offers two choices: going to the police to “let them insert some kind of kit into you,” then going to trial and spending money on lawyers that could be better used “sending you to Europe or buying clothes for a job interview”; or, choice number two, “chalk this up to a misunderstanding and never think about it again.” And when Jerene says never think of it, she means it:

I have no intention, Jerilyn, of paying for ten years of therapy as you relive and relive it, and—oh whatever you see on Oprah these days from people who can’t buck up and move on. There’ll be no hating yourself and turning to drink and pills….

Jerene is the supreme bucker-upper. And it turns out she has had quite a bit to buck up from. She grew up trying to dodge a drunken, physically abusive father, trying to please a spiteful, demanding, emotionally dessicated mother, trying to outwit and leave behind a teenage pregnancy. Slowly, in glancing references, we are allowed to glimpse what Jerene has been up against, and her weird, brittle energy and striving begin to look a lot like strength of character. Strength of warped character, but nevertheless.

Jerene is devoted to her family legacy, by which she means some paintings she inherited. Her real family legacy, all generations of it, is far more complicated. When Annie, her oldest daughter, refused to have a debut so many years ago, Jerene appealed to her sense of duty “to the generations before and after.”

“You think a debut and all this society stuff is bullshit,” she began. Annie certainly was surprised to hear her mother say it, booolshit, with her melodic cadences. “Well, I agree with you. You want to be a rock ’n roller or some kind of revolutionary? I have news for you: there’s bullshit in those worlds too. In every walk of life, there are senseless rules, payoffs and shakedowns, quirks, unjust rituals…. You want to go work in a women’s shelter and give away all your debutante money? Go see what kind of dreadful politics and chicanery reigns in those charitable organizations…. I know from my involvement in years and years of committee work that the booolshit you are too good for is lying thick on the ground in all aspects of life.”

Jerene is smart, the smartest of the bunch, and terrifyingly unsentimental. Every bit of her intelligence is needed to keep her family where she wants it: prominent in Charlotte society. The rest of the Jarvis/Johnston clan are just not as good at handling the booolshit.

Annie remains a politically self-righteous daughter, rebelling against her parents long after they have lost interest in her now middle-aged radical ranting, marrying the wrong men, and blaming her weight for everything wrong in her life. Jerene’s oldest son, Bo, is a mildly pompous Presbyterian minister with less faith than he would wish and far less charisma than his parishioners would like. Bo is married to a straightforward, plain-talking young woman who wants only to feed the poor, church politics be damned, while Bo leans more and more toward exactly the hierarchical and career-improving part of church life.

The younger son, Josh, is a gay guy without ambition of any kind who works in a clothing store. His best friend, Dorrie, an African-American lesbian, accompanies him to every family function, listening with quiet contempt to the antebellum nostalgia, though she, too, takes pride in her bloodlines, which run back to New Orleans in the seventeenth century. Jerene’s sister, Dillard, is a sad sack suffering from every condition for which a medicinal remedy is advertised on television.

Then there is the Jarvis grand dame, Jeannette Jarvis, placed in a luxurious retirement home with the services of a deluxe hotel because her children thought she had only a few months left to live. That was four years ago. Jerene and Dillard can no longer afford the fees. Gaston, who has plenty of money, will not contribute one penny to his mother’s upkeep. “You see now,” Jerene tells her, “the long-term disadvantage of allowing your children to be your buffer against a brute of a husband.”

Jeannette is a poisonous narcissist, but through Barnhardt’s narrative generosity, even she gets her say, recalling her

realistic fears of falling headlong out of Society and back into the peasantry, the white trash, to have once been something and then to go back to nothing again.

It turns out, however, that even the patina of southern society she worked so hard to obtain is booolshit:

“Jeannie,” your daddy would tell me, “everybody down South got rich doing something they shouldn’t have.” I can name you the first families of the Carolinas who got rich on smuggling or selling to the British in the Revolutionary War—or the Yankees, mind you.

The cream of southern society started out as bootleggers, she says, or carpetbaggers, buying up land in the Depression, hiring goons to run off the squatters, nightriders to burn “the colored folk out of their shacks.” The precious Jarvis family legacy that Jerene is so proud of is not exempt:

It is naive to think anybody that has money got it without doing something really bad because it is much easier to be poor—that, my girl, is the natural state of things. Money runs out, money gets spent. To have so much of it that it doesn’t run out or get spent means something…unpleasant had to happen somewhere along the way.

The Jarvis unpleasantness is unpleasant, indeed—a long-standing and vicious charade. When Jerene realizes how much of the family mythology she has been disseminating is just that—mythical—her mother reassures her:

You didn’t know they were lies, Jerene. And people like those kind of lies down here. They’re good, entertaining lies—I suspect history is eighty percent those kind of lies.

With this Gothic family birthright, the Jarvis/Johnston family dinners are, not surprisingly, exquisite disasters. Gaston won’t attend even Christmas dinner if his mother will be there, so they come on alternate Christmases. It being his year, he arrives with a case of excellent wine and the fatted goose is immediately surrounded by bitter arguments and sullen grudges and ultimately a shot fired from an 1854 dueling pistol that changes everything. Yet in some ways, thanks to Jerene, even the scandal of a wife shooting her husband changes nothing. Jerene—implacable, all powerful, sharp, and piercingly funny Jerene. She is the tragic hero of the novel.

But so is the South itself, rising and falling and rising again, the Old South clinging to the heels of the New South. Barnhardt has much to say about Dixie, all of it with the love and disgust we save for those we love the most:

Southerners. Such literate, civilized folk, such charm and cleverness and passion for living, such genuine interest in people, all people, high and low, white and black…[yet] how often cities had burned, people had been strung up in trees, atrocities had been permitted to occur…. How could one place contain the other place?

It’s a question Barnhardt cannot answer, only illustrate.

When Gaston and Duke are students, Gaston plans, in the grandiose way of the young, with Duke’s grandiose encouragement, to write an important novel about the South. “Faulkner, Duke declared, had masterfully written about the post-Reconstruction South—there was no need to ever visit any of that again, for a white writer, at any rate. But what of the way we live now?” Gaston has no interest in the New South, which he sees “sinking into the monoculture of the United States, deracinated. No, it needs the grandeur of an earlier era.” And the book must be about a southern family as it rises and falls:

“They must not simply rise and fall,” Duke had said. “They have to embody the central conundrum of the South.”

“You mean, race?”

“There’s something fatal from what the slave trade fostered, a kind of barbarism side by side with the civility.”

This “something fatal” runs through the book like a quiet underground river, polluting as well as irrigating a culture that has not yet lost itself entirely in the “monoculture” of the country. There are no moral lectures in Lookaway, Lookaway; there aren’t even any lessons. But there is passion. It is a work that hides its craft but never its beauty, that is ambitious but never pretentious, that does not sacrifice nuance for power or power for nuance. The book’s careful, formal composition is invisible as you read, and it’s a beautiful read, sad and savagely funny, one place inexplicably contained in the other.