If this collection of Bertolt Brecht’s poems in English were half its length, it would be great; if a third, spectacular; if a quarter, indispensable. The book it replaces, the 1976 Methuen Poems 1913–1956, edited by Ralph Manheim and John Willett (and mostly translated by Willett and by Michael Hamburger, though there are thirty-five contributors in all), can, at a featly 627 pages, be picked up and carted around and read and held in the mind. This new translation, six hundred pages longer and in a bigger, outsize format (one that resists flipping and browsing), just about can’t. The gigantism perplexes me.

Do we really have such gargantuan appetites for (mostly small) poems? It seems to take an unduly long time in the new collection, translated and edited by Tom Kuhn and David Constantine, before one reaches familiar ground: the ballad of the serene parenticide Jakob Apfelböck, called “Apfelböck or the lily of the field,” is on page 166 (24 in Manheim/Willett); “Remembering Marie A.” on page 220 (35 in Manheim/Willett); “Poor B.B.,” one of the great twentieth-century poems, which Brecht wrote in piquant circumstances at the age of twenty-four on the night train from Berlin—which was in 1922 still resistant to his appeal—to his long-since-outgrown hometown of Augsburg, on page 250 (107 in Manheim/Willett).

Nor is this just a matter of some peculiar familiarity fetish; the first time I encountered a little run of poems I enjoyed and thought were worth reading (which is surely how a big book like this sinks or swims), it was after page 50. The Psalms of 1920 are magically disobliging things, full of celestial surliness: “Our dwelling place was a black hut by the river. Often and grievously the horseflies bit her white body. I read the newspaper seven times, or I said: Your hair is the colour of dirt. Or: You are heartless.” Nor should one suppose the Kuhn/Constantine has simply eaten the whole of Manheim/Willett; there are things in the latter bafflingly not included in the former, great things, too: the seven-page apocalyptic jeer called “Late lamented fame of the giant city of New York,” a poem I often think about and always look for, never more apposite than now; one of the best of the subtle and thought-provoking “theater poems,” called “Speech to Danish working-class actors on the Art of Observation”:

You, actor

Must master the art of observation

Before all other arts.

For what matters is not how you look but

What you have seen and can show us. What’s worth knowing

Is what you know.

People will observe you to see

How well you have observed.

Or a tiny (and very early!) existential rien called “Born Later”:

I admit it: I

Have no hope.

The blind talk of a way out. I

See.

When the errors have been used up

As our last companion, facing us

Sits nothingness.

“Der letzte Gesellschafter”—the German for “our last companion”—comes unbidden. I find it rather strange to imagine the new editors thinking their book of 1,200 pages is the better for not having these wonders.

In the ruck of poets, I see Brecht as always having faced the other way: they are inoffensive linemen; he practices judo. He was a born contrarian, made all the more so by his experience and the habit of dialectics. “From the very start,” as he says in “Poor B.B.,” he showed a hatred of depth, a hatred of beauty and spirituality, a hatred of sentiment, a hatred of fake velvet and ten-cent words. He disdained these standbys of most other poetry as valueless, stupid, ineffectual. Asked, as a young poet himself, to judge a contest for young poets, he made no award but said he would like to ban sleeves (to shake something out of one’s sleeve is a German expression for doing something effortlessly and fatuously). Poetry isn’t a numinous waft to Brecht, it’s a targeted effect. He offers a liking for thought and an awareness of the shape of thought, the correction of popular idiocies and foul politics, a willingness to contradict, to mock, to doubt. He is agile in his positioning, admirable in his detachment, dependable in his sobriety. His favorite book? Don’t laugh, he said, the Bible.

Slight, surprising shifts in logic or phrasing are hugely, disproportionately, unforgettably effective. The style is economical, the manner the personal/impersonal of folk poetry: “When the wound/No longer hurts/The scar does”; “Carefully I test/My plan, it is/Good enough, it is/Unrealizable”; “It is night./The married couples/Take themselves off to their beds. The young women/Will bear orphans” (from the “German War Primer”); “Their mothers gave birth in pain, but their women/Conceive in pain”; a host people (the Swedish Finns) is described as “mute in both its tongues,” or, better, in Michael Hamburger’s old translation, with intentionality, “silent in two tongues.” Such qualities culminate in the famous late poems, such as “Changing the wheel”:

Advertisement

I am sitting by the side of the road.

The driver is changing the wheel.

I don’t like where I was.

I don’t like where I am going to.

Why do I watch the changing of the wheel

With impatience?

(Again, I like the Hamburger translation better: “I do not like the place I have come from./I do not like the place I am going to.”) Or “The Solution,” which goes, in its entirety:

After the uprising of 17 June

On the orders of the Secretary of the Writers’ Union

Leaflets were distributed in the Stalinallee

Which read: that the people

Had forfeited the government’s trust

And only by working twice as hard

Could they win it back. But would it not

Be simpler if the government

Dissolved the people and

Elected another one?

To Brecht, a poem—say, the poems on the theater, the sonnets on books, the reflections on current events and on his own life—comes to be simply the most stringent and economical mode of presenting an argument. Not the least attractive aspect of him is that he remains subversive, modest, trenchant; he doesn’t crow, doesn’t bully, doesn’t tub- or chest-thump. There is always wit, and often delicacy; you see him taking care where he places his feet. In the poem “Letter to the workers’ theater,” he describes himself accurately as writing “without digressions, in spare language/Placing my words cleanly, choosing/Every gesture of my figure with care, as one/Reports the words and deeds of the great.”

“He made suggestions,” he proposes as an epitaph for himself, and the poetry is a suada, a plea, or a series of suadae—correct, purposeful, well intentioned but ringingly unsuccessful. It didn’t overturn the German bourgeoisie, didn’t defeat Hitler, didn’t sink capitalism, and didn’t prompt his East German masters to rethink their dim project. The lack of success is important, and is a reason to read him, not the opposite. Poetry doesn’t take the cause of the victor. A little four-liner leading off Brecht’s final collection, Buckow Elegies (unpublished in his lifetime), goes:

If there were a wind

I could put up a sail.

If there were no sail

I’d make one of sticks and canvas.

Note that when the speaker tells this political parable, there is still no wind, and the vessel, if there is a vessel, is still becalmed (neither circumstance receives any commentary), but Brecht to the last remains committed to his singular, meliorist, somehow heroic, homemade endeavors. He was always much more Hamlet than Fortinbras.

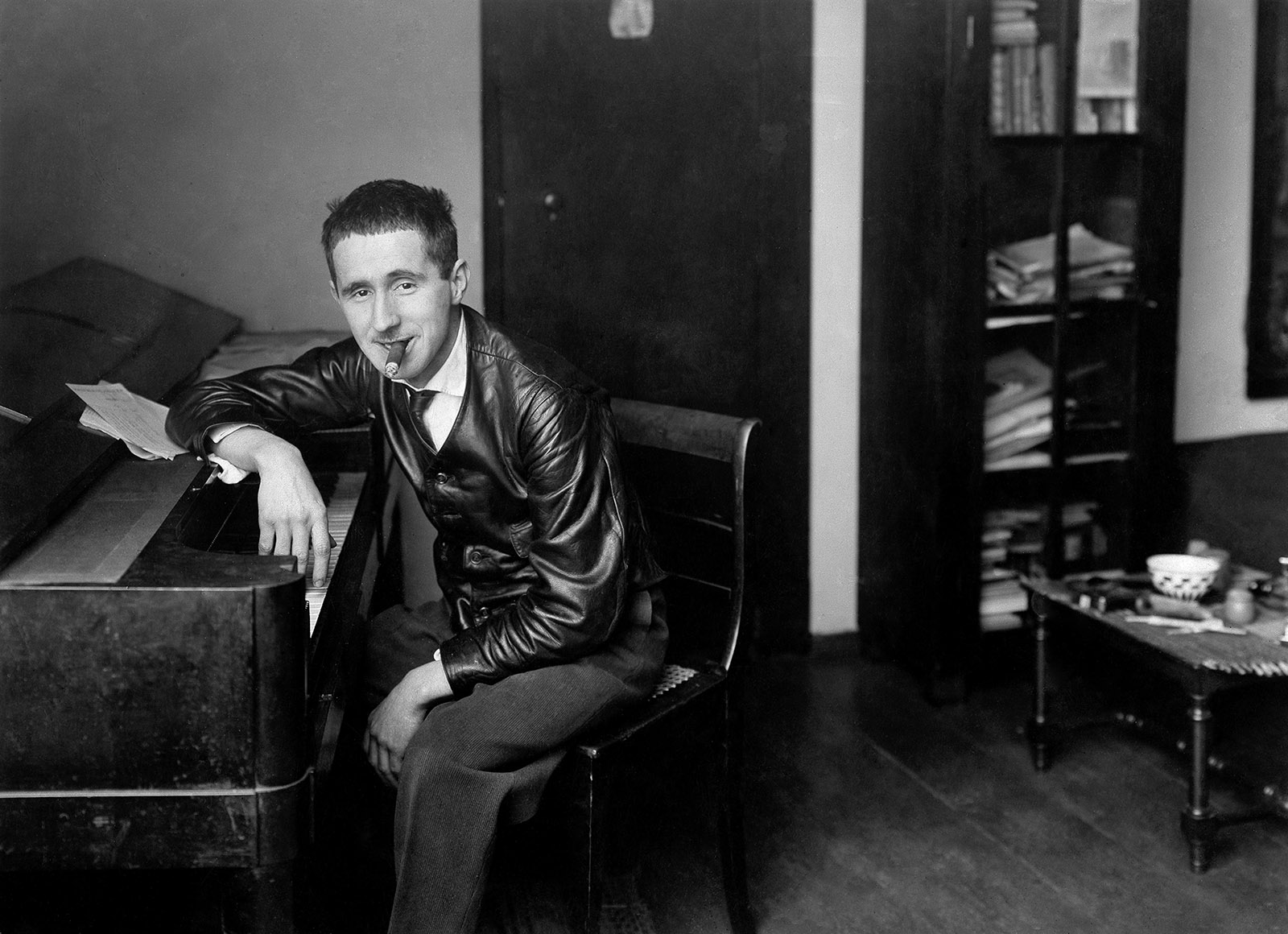

Brecht’s biography exhibits the range and vicissitudes required of the twentieth-century poet, the one constant being prodigious, almost continuous work. Like his concept of “epic theater,” the life seems a succession of opposing tableaux. The idyllic childhood, brought to an abrupt conclusion by the early death of his mother and the conscription of his friends in World War I. The provincial upbringing in Bavaria, cock of the walk in Augsburg, where he rapidly fathered three children with three different women; then the unavoidable but difficult move to the “cold Chicago” of Berlin. The years of honorable and (mostly) dishonorable, Machiavellian striving; the award of the Kleist Prize in 1922, when he was still in his twenties. The rackety, scandal-ridden, publicity-hungry 1920s; the indestructible domestic set-up with the actress Helene Weigel. The huge—but knife-edge—success of The Threepenny Opera in 1928 and Brecht’s subsequent perverse determination to make only the most unwatchable doctrinaire shows thereafter.

The wildly original and enduringly interesting theater ideas (“Showing must be shown,” as the poem title has it) evolved over decades, from first principles, and largely in the absence of any theaters. The purchase of a house in Bavaria in 1932 (“Seven weeks of my life I was rich”) and the overnight flight to exile in Denmark following the Reichstag Fire. The alternations of power and powerlessness, charisma and neglect, happy collaboration with a succession of gifted (and usually female) actors and writers, and a desolation that left him almost depressed (though he might just be the only undepressed poet there has ever been). The dramatic flight up through Scandinavia (“High up in Lapland/Towards the northern ice sea/I still see a little door”) and across Stalin’s Soviet Union to Vladivostok and the last steamer (the SS Annie Johnson) crossing the Pacific before Japan entered World War II, and the terrible flat calm of Hollywood: “Every morning, to earn my bread/I go to the market where lies are traded/In hope/I take my place amongst the sellers.”

Advertisement

The writing of one play after another in the 1930s and the final granting of his long-standing wish for a theater to manage, as implied in the proud, though always provisional-sounding, poem “1954, first half,” reversible and subtractable, as all lists are: “I saw the lilac in Buckow, the marketplace at Bruges/The canals of Amsterdam, Les Halles in Paris./I enjoyed the friendship of the lovely A.T./I read the letters of Voltaire and Mao’s essay on contradiction./I put on the Chalk Circle at the Schiffbauerdamm.” Ending his days as the uneasy state poet in the state of his dreams (not!), the Communist GDR, with his writings published in the Federal Republic (West Germany), his plays produced in Milan, his money parked in Switzerland, and the nationality of his passport—Austrian, if you please. Who can hope to have a simple, straight life in such crooked times? But there is something also representative about it. It is the life of a twentieth-century writer, not all that different from the lives of Achebe or Baldwin, Bei Dao or Brodsky, Herbert or Breytenbach, Neruda or Tsvetaeva: talent the motor, the anchor, the cargo; a work on the horizon; everything else (even language) negotiable.

All this—and much more—is reflected, sometimes obliquely, sometimes straightforwardly, sometimes excerpted, sometimes bunched together, in the poems. This is where Brecht records Franz Wedekind’s funeral and Alfred Döblin’s “10,000th birthday,” the pendulous belly of Charles Laughton and the actor’s garden overlooking the Pacific (“It seems/There’s not much time in which to complete it”). He writes love poems of every stripe, from cynical to sad to sweet (these were in Love Poems, released by the same translators in 2014—the single, so to speak, from the album now under review). He writes poems of advice, criticism, demurral. He writes poems to stabilize or situate himself. That’s probably what Brecht meant by the otherwise puzzling sentence given much prominence in the Willett/Manheim introduction: “The thing is that my poetry is the strongest argument against my play-writing activities.”

The plays, obviously distanced, obviously deliberate, obviously fictive crucibles, ethical-political in intention, obviously like nothing else—we’d known about those since the international Brecht boom of the 1950s. It was a matter in 1976 of revealing Brecht the poet (the introduction is even called “Disclosure of a Poet”) in his full excellence and variety to an ignorant and unprepared world, since translations to that point had been too few and too bad. The Anglo-American world now may still be ignorant, but it cannot be called unprepared—or maybe the other way around—yet there remains a distance, an apprehension. It may be that the idea of a poetry so built around cleverness, so diagrammatic, fails to find favor; it may be Brecht’s theoretical and political baggage (one never really warmed to the Alienation Effect, and has little sympathy for an old buttoned-up Communist); it may be his perceived detachment from the traditional murk of poetry (we are still addicted to the old gravy browning); it may be an unappeased irritation with translation.

Brecht has a knack of writing ordinary German and meaning it that makes him extraordinarily difficult to translate—maybe (surprisingly) the hardest of all the twentieth-century Germans. Of Rilke the similes survive, even if they baffle as they dazzle; of Trakl something gaudy and barbarous; of Celan the twist of an opaque pain; of Benn the human mutter. In Brecht, simple words (kalt, fahl, früh, böse) and plain statements are asked to bear an awful lot of weight. The great poem “An die Nachgeborenen,” written in 1938, a confession of inadequacy to coming generations, has a stanza that goes:

Die Kräfte waren gering. Das Ziel

Lag in großer Ferne

Es war deutlich sichtbar, wenn auch für mich

Kaum zu erreichen.

So verging meine Zeit

Die auf Erden mir gegeben war.

Not one word sticks out, sounds pretentious or hollow, even though the plural Erden is archaic. Abstraction and concreteness, the personal and impersonal, are held in exquisite balance. The whole thing has a gravity and stateliness of centuries. The stanza, in Tom Kuhn’s English version, “To those born after,” goes:

Our powers were feeble. The goal

Lay far in the distance

It was clearly visible even if, for me

Hardly attainable.

Thus the days passed

Granted to me on this earth.

Here, there’s just one odd- or off-sounding word after another: “powers” (what powers be these? magic powers? dark powers? height of his powers?), “feeble,” “goal” (though perhaps the fault is with the article), “thus” (always a little high-smelling in English), “granted.” The poem, which in German sounds universal, sounds in English equivocal, vague, even a little coquettish. The lines—and hence the action in them—have an uncertain tempo (“days,” when it comes, is a surprise), and hence an uncertain weight. Edwin Muir, you think, does this kind of ominousness much better. The Manheim/Willett translation (it’s unsigned, and hence collaborative) goes:

Our forces were slight. Our goal

Lay far in the distance

It was clearly visible, though I myself

Was unlikely to reach it.

So passed my time

Which had been given to me on earth.

This seems preferable to me all over. A lot of translating is the avoiding of weakness, or the needless display of weakness; hence no “the goal” and no “thus”; the active construction in the middle with the emphatic “I myself” followed by the (very English!) understatement of “was unlikely” is cleverly done; and “time” and “given” are better than the more portentous “days” and “granted.” The last line has altogether more force and purpose. (This is something one sees a lot more of in the rhyming poems; the lines are allowed to go at will; they become something like bouts rimés.) Similar tendencies are observable throughout the poem.

In other stanzas Kuhn makes more words (“Yet I do eat and I drink” for “And yet I eat and drink”), and his diction produces a sort of watery overcomplication (“A conversation about trees is almost a crime/Because it entails a silence about so many misdeeds!”—entails? misdeeds?—for “A talk about trees is almost a crime/Because it implies silence about so many horrors”; or “To hold yourself above the strife of the world and to live out/That brief compass without fear” for “To shun the strife of the world and to live out/ Your brief time without fear”). His conclusion doesn’t have the requisite firmness:

And yet we know:

Hatred, even of meanness

Makes you ugly.

Anger, even at injustice

Makes your voice hoarse.

(The second person—which should not be in play here anyway, as the poem is in the form of an address, and so “you” was used earlier correctly, and, more important, will be needed later—is a bad mistake.)

Kuhn’s version of the poem goes on:

Oh, we

Who wanted to prepare the land for friendliness

Could not ourselves be friendly.

You, however, when the time comes

When mankind is a helper unto mankind

Think on us

With forbearance.

The Manheim/Willett version ends:

And yet we know:

Hatred, even of meanness

Contorts the features.

Anger, even against injustice

Makes the voice hoarse. Oh, we

Who wanted to prepare the ground for friendliness

Could not ourselves be friendly.

But you, when the time comes at last

And man is a helper to man

Think of us

With forbearance.

Kuhn’s “think on” and “mankind” and “unto” stand revealed as forced and unnecessary and a little histrionic—all, of course, damaging to the poem.

Another poem that I’ve long adored, very different, so different that the two editions end up putting it at opposite ends, is “What Orge wants,” or, in Manheim/Willett, “Orge’s list of wishes.” (Orge is a friend of Brecht’s youth, one Georg Pfanzelt.) In Lesley Lendrum’s rollicking Byronic version it sets out:

Of joys, the unweighed.

Of skins, the unflayed.

Of stories, the incomprehensible.

Of suggestions, the indispensable.

Of girls, the new.

Of women, the untrue.

Of orgasms, the uncoordinated.

Of enmities, the reciprocated.

Of abodes, the impermanent.

Of partings, the unexuberant.

(Note how much “Brecht” is contained, prospectively or retrospectively, even in this jolly doggerel.) David Constantine does it altogether more circumspectly and constrainedly:

Of joys, the full-blown.

Of skins saved, one’s own.

Of stories, the unintelligible.

Of counsels, the unusable.

Of girls, the new.

Of women, the untrue.

Of orgasms, the not together.

Of enmities, the one another.

Of sojourns, the not-here-to-stop.

Of partings, the not-over-the-top.

Where Lendrum hurdles each rhyme enthusiastically and triumphantly, Constantine in the modern manner wangles around them like someone mimicking the double helix. This, too, is something one sees much more of in the book, a rather sheepish or defensive rhyming, rhyming that may even go unnoticed first time around, but can be pointed to later. When I took out my copy of Jan Knopf’s 2000 Suhrkamp edition of Brecht’s Gedichte, I was quite startled by the general level of exuberance and inventiveness. His spiritedness has gotten lost somewhere.

It’s never good news when something new isn’t as good as something old, particularly when the old thing is being replaced by the new one. I’m sure, over the long length of the book, there will be many more pluses and minuses. The Psalms, as I say, read well, and a couple of the simpler, briefer sequences brushed up nicely, such as the “German War Primer” in the Svendborg Poems; and “The Reader for City Dwellers,” like a little existential undercover spy sequence, especially #9, but also lines like “We don’t know what’s coming/And have nothing better to offer/But you, we don’t want anymore,” or “Let go of your dreams/That exceptions will be made for you./What your mother said/Was not binding.” The notes and brief texts between sections (in an otherwise rather fussy and oversegmented book) are good. If you don’t mind halfhearted smut (the originals are spirited), you will like some of the “pornographic” sonnets; I think the best joke is that Brecht signed one of them “Thomas Mann,” an unlikely ascription to the vague heterosexual and father of six.

I have every expectation that when a 200- or 300-page selection is made from this collection—what the film people call “exploiting the rights” to it—it will be an important book, and something everyone should have. That is really the one Brecht readers (and nonreaders) have been waiting for, and are still waiting for. But for now, to experience Brecht, listen to some of the Kurt Weill or Hanns Eisler settings, read Stephen Parker’s outstanding biography, and teach yourself German.

This Issue

December 20, 2018

Damn It All

Prodigal Fathers

In the Valley of Fear