1.

Conventional wisdom holds that the most enticing way to introduce architecture to a lay audience is through the human element that animates this most social of all art forms. Nowhere is that inducement clearer than in books that deal with the private lives of famous architects, which are far more likely to engage general readers than recondite technical treatises or the abstruse theoretical cogitations that have long dominated academic architectural publishing.

Domestic architecture in particular frequently arouses deep personal emotions between designers and clients, sometimes with life-changing consequences, and thus is catnip to savvy publishers. For example, in 1903 the Chicago electrical engineer Edwin Cheney asked Frank Lloyd Wright to design a house for him and his family in suburban Oak Park, which led to an affair between the architect (a married father of six) and Cheney’s beautiful, headstrong wife, Mamah Borthwick (the mother of their two children). The errant couple went on to live together without benefit of divorce and remarriage, which caused a national scandal that culminated in 1914 with the murder of Borthwick and her offspring at the hands of a psychotic servant; the ensuing notoriety undermined Wright’s career for three decades.1 This overfamiliar saga was rehashed yet again in Paul Hendrickson’s Plagued by Fire: The Dreams and Furies of Frank Lloyd Wright (2019), which added little to what we already knew.

In post–World War II America, the architectural liaison dangereuse that generated the most press coverage (as well as prurient speculation) concerned Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Dr. Edith Farnsworth, respectively the designer of and the client for the Farnsworth house of 1945–1951 in Plano, Illinois, which is inevitably included on lists of the twentieth century’s most exceptional dwellings. During the building’s long, slow realization, their once warm (and, in the opinion of several observers, intimate) relationship cooled so much that they wound up in court to dispute the job’s financial resolution, though at the beginning theirs seemed an ideal pairing of Olympian artist and adoring acolyte.

Hero-worship of artists is always risky, and Farnsworth’s expectation that Mies would be a tractable architect now seems heedlessly misconceived. Although he had built relatively little before he came to the US a decade earlier, both his pre-war European projects and postwar American schemes clearly displayed disdain for bourgeois comforts of the sort that Farnsworth complained were absent from the house (even though this was a custom commission that she approved down to the smallest detail). Mies’s austere design ethos demanded a renunciation of physical and psychic ease, a desire for which remained prevalent even among those who favored progressive design over traditional revivalism. This led to the vogue for Art Deco and Streamline Moderne—two commercially successful adaptations of European modernism welcomed more eagerly by Americans than Mies’s reductive International Style, which was championed by the Museum of Modern Art from its founding in 1929.

Two years after the Farnsworth house was completed, it was roundly disparaged in House Beautiful magazine, then a principal arbiter of middlebrow domestic taste. Its xenophobic editor, Elizabeth Gordon, saw European modernism as an alien import that imperiled nativist values. In an essay of her own, part of the magazine’s 1953 broadside “The Threat to the Next America,” Gordon displayed McCarthyite cunning by equating advanced modern architecture (which had been quickly embraced on the West Coast and influenced residential construction all across the country at a time of unprecedented suburban development) with totalitarianism. Her reactionary stance was humanized by her portrayal of Farnsworth as “a highly intelligent, now disillusioned, woman who spent more than $70,000 building a one-room house that is nothing but a glass cage on stilts.”

But if anyone was qualified to expound on the relationship between design and dictatorship it was Mies van der Rohe. In 1938 Mies, the last director of the Bauhaus (which he had disbanded five years earlier under Nazi pressure), reluctantly quit Germany, where his professional prospects were nil. This was not because of any hesitancy on his part to accept commissions from the Hitler regime, which he solicited to no avail, but because his severe Modernist architecture—stigmatized by the Nazis as “Bolshevist”—was the antithesis of the Führer’s preference for monumental Stripped Classicism in the public realm and a völkisch vernacular in the everyday sphere. Deliberate to a fault, the habitually indecisive Mies was impelled by this career impasse to make the luckiest move of his life.

He reestablished himself not in New York, Los Angeles, or Cambridge, where many of his refugee compatriots had found rewarding work, but in Chicago. There his no-nonsense approach to design fit in perfectly with the city’s preferred mode of clear modern structural expression—as promulgated by audacious pioneers from the mid-nineteenth century onward: William LeBaron Jenney, William Holabird, John Wellborn Root, Louis Sullivan, Daniel Burnham, and other leaders of the so-called Chicago School—of which Mies’s highly rationalized “skin-and-bones” architecture gave a strong contemporary reinterpretation.

Advertisement

Furthermore, his unexecuted visionary schemes of the 1920s for steel- framed, glass-walled skyscrapers (technically impossible to execute at that time) would find fulfillment in the birthplace of the tall building, which conclusively signaled the tectonic shift in architectural innovation from pre-war Europe to postwar America. Mies’s salary as head of the architecture school at Chicago’s Armour Institute of Technology (later renamed the Illinois Institute of Technology) and master planner for its new South Side campus allowed him to wait out World War II and lay the groundwork for his personal practice once civilian construction resumed. Thereafter, Mies’s reinvigorated and vastly expanded career would confirm him as among the two or three most influential architects of the twentieth century, and by far the most successful of the many European architects who escaped Hitler.

In 1913 this taciturn son and grandson of Catholic stonemasons from Aachen married the upper-middle-class Ada Bruhn, daughter of a nouveau riche Berlin industrialist. By the time she bore him three daughters he had tired of family life, and their marriage was effectively over after five years, though he never sought a divorce. (“A no-divorce was convenient for him,” Mies’s daughter Marianne Lohan believed. “It gave him freedom,” as well as an excuse for never remarrying.) In the mid-1920s he began a thirteen-year affair with Lilly Reich, his chief interior design collaborator, but when he departed for America he abandoned all five women to fend for themselves in Germany during World War II.2

On New Year’s Eve, 1940, Mies met Lora Flanegin Marx, a vivacious Chicago divorcée and sculptor whose ex-husband, Samuel Marx, was a fashionable architect and furniture designer. These two hearty drinkers hit it off instantly and stayed together despite sporadic breakups until his death, but there would be other women in his life, too. At a dinner party in 1945 the sixty-year-old architect was seated next to the forty-two-year-old Edith Brooks Farnsworth. Daughter of a rich Chicago lumber-and-paper executive, she was intelligent, well educated, unmarried, and harbored artistic yearnings. She had taken a degree in literature at the University of Chicago but then studied violin in Italy with Mario Corti, a much older virtuoso with whom she apparently had an affair. But fearful that she wasn’t good enough for a top-flight concert career, she switched to medicine and became a respected nephrologist.

On the night Farnsworth first encountered Mies, she asked him if some young associate in his office might design for her a simple weekend house for between $8,000 and $10,000. It was to be built on a nine-acre wooded riverside site some sixty miles southwest of Chicago that she’d recently bought from Robert McCormick, the archconservative owner-publisher of the Chicago Tribune and a leader of the pre-war isolationist America First movement. Never one to miss an opportunity, Mies immediately agreed to do it himself, with one proviso. As he later testified, “I told her I would not be interested in a normal house, but if it could be fine and interesting, then I would do it.” In the gap between what he said and what she heard, there yawned an abyss of misunderstanding that would ultimately engulf them both. One of Mies’s employees remembered that Farnsworth had urged his boss to “‘build it as if you were building it for yourself.’ I don’t know what was said and what was understood, certainly I had understood that he would be using it.”

It was during one of Mies’s periodic separations from Marx—she could no longer tolerate their codependent binge-drinking sprees and entered Alcoholics Anonymous, which he refused to do—that he began a dalliance with Farnsworth that seems to have lasted only a year or so. Her sister thought she “was mesmerized by [Mies] and she probably had an affair with him,” but such matters cannot be verified without the confirmation of the principals, which neither ever gave.

2.

The result of this serendipitous encounter was the Farnsworth house, a white-steel-framed, glass-encased flat-roofed oblong that measures twenty-eight by seventy-seven feet and hovers almost weightlessly five feet above the ground on eight slender posts. Mies’s arresting apparition distills the concept of shelter to an almost irreducible Platonic essence, which he famously described as beinahe Nichts—nearly nothing. Yet achieving such pinpoint perfection required concentrated effort and enormous expense.

Although the amount of personal interaction a client has with an architect can vary greatly from project to project, by any standard Farnsworth injected herself into the design process to an extraordinary degree. In Broken Glass: Mies van der Rohe, Edith Farnsworth, and the Fight Over a Modernist Masterpiece, the nonfiction writer and novelist Alex Beam insists that by 1948, a year after the two first met, “she was Mies’s client, but not a girlfriend, mistress, or lover.” Throughout their six-year project she spent an inordinate amount of time obsessing over it, both by herself and in his presence. She and Mies made frequent trips to the building site at her behest, and she visited his Chicago atelier so often that one assistant recalled, “She used to come to the office just about every other Thursday” and “almost every Saturday afternoon.”

Advertisement

The Farnsworth house is the subject of Beam’s book, a current exhibition in the building itself, a recent scholarly article, an off-Broadway play, and a forthcoming Hollywood film, which says as much about the intense focus that surrounded its exacting realization as it does about its turbulent backstory. The renewed attention to this small, 1,500-square-foot structure—revered though it has always been by experts—is further noteworthy because of a concurrent revisionist appraisal of Farnsworth herself.

A notable text in this shifting perspective is the architecture professor Nora Wendl’s essay “Uncompromising Reasons for Going West: A Story of Sex and Real Estate, Reconsidered.”3 In it she objects to Farnsworth being characterized as an embittered, jilted spinster and her legal proceedings against Mies as retribution for his breaking off their alleged affair, rather than an expression of her legitimate grievances about its excessive cost. (This was finally calculated by Mies’s office at $79,000—the equivalent of about $800,000 today—about ten times what Farnsworth had initially told him she could spend.)

Wendl attributes the stereotype of Farnsworth as a vengeful Fury to an unverified remark cited in an unsigned Newsweek editor’s note soon after the designer’s death: “Mies and Dr. Farnsworth were good friends and Mies once cracked that Dr. Farnsworth’s discontent occurred because ‘the lady expected the architect to go along with the house.’” In an unfinished autobiography Farnsworth betrays a lingering animus when she writes of Mies, “Perhaps it was never a friend and a collaborator, so to speak, that he wanted but a dupe and a victim.”

The Newsweek quotation made it into Mies van der Rohe: A Critical Biography, the architectural historian Franz Schulze’s definitive life-and-works, which was published in 1985 and reissued in a revised edition (with Edward Windhorst) twenty-nine years later.4 Schulze portrayed this architect/client dynamic as an unfortunate mismatch between the smart, accomplished, but irredeemably unhappy Farnsworth and the pragmatic, self-centered, and ever-opportunistic Mies. In terms that some today would denounce as “lookist,” Schulze wrote that Farnsworth was “no beauty. Six feet tall, ungainly of carriage, and, as witnesses agreed, rather equine in features, she was sensitive about her physical person.” It remains unclear if Mies’s biographer saw her appearance as a factor in her failed relationship with the architect.

Schulze’s visual description of Farnsworth, accurate though first-person accounts may confirm it to be, is less important than the haughty way she behaved toward those she deemed beneath her intellectually or socially, which was unattractive by any definition. In Broken Glass Beam convincingly shows, through extensive quotations from interviews and trial transcripts, that she was acerbic, intolerant, snobbish, dismissive, and demanding. “She had a very sharp tongue,” reminisced one of the Plano neighbors she befriended, “and she was quick to be critical of almost anybody even if you were sitting there.” Beam is hardly unsympathetic to Farnsworth, whom he does not see as a furious woman scorned. Yet his depiction is at odds with Wendl’s view of her as a victim of double standards, blatantly sexist attitudes, outmoded social restrictions, and insidious institutionalized inequality.

Beam presents Farnsworth as an unfulfilled woman who had the financial means to repeatedly switch professional pursuits—by turns performing classical music, practicing medicine, and translating Italian literature into English—in perpetual search of some elusive satisfaction she could never find. But was she a victim of sexist circumstance, the entitled recipient of privilege that fed her high self-regard, or some blend of both? The most insightful and nuanced answers to those questions can be found in the architectural historian Alice T. Friedman’s chapter on the Farnsworth house in her brilliant Women and the Making of the Modern House: A Social and Architectural History (1998). Although Friedman gives full voice to the inhibiting pressures to which women of Farnsworth’s generation, especially unmarried women, were subjected, she is careful not to overemphasize that factor to the exclusion of the very personal forces at play in this instance:

Neither Farnsworth’s conflict with the architect nor the unprecedented design of the Farnsworth House was simply the result of her being a woman. Many works of architecture, built for a variety of clients and purposes, have similar histories: there are often persistent and unresolved questions about power, professional status, money, and, ultimately, about who is in control of the project….

What is unusual in this case…is that questions of gender and sexuality were explicitly focused on by the participants, and that they came to assume an unusually prominent and complex role in the design process.

Not the least of Farnsworth’s laments about her house was its merciless lack of privacy; she felt that its glass walls exposed her to public view like a fish in an aquarium. That factor—central to the scheme from the beginning—is emblematic of Mies’s constitutional indifference to the desires of others, an outlook reflected as much in his designs as in his private life. Even the presumed power of her controlling the purse strings on the commission eluded Farnsworth, and as Friedman writes, the problem was at least in part generational:

Edith Farnsworth may have been a successful doctor, but the fact that she was also a single woman made her more dependent on the architect both personally and professionally. Ambiguities about their roles, not simply as architect and client but also as man and woman, blurred the boundaries of their relationship, which was especially problematized by the attitudes and prejudices of 1950s America.

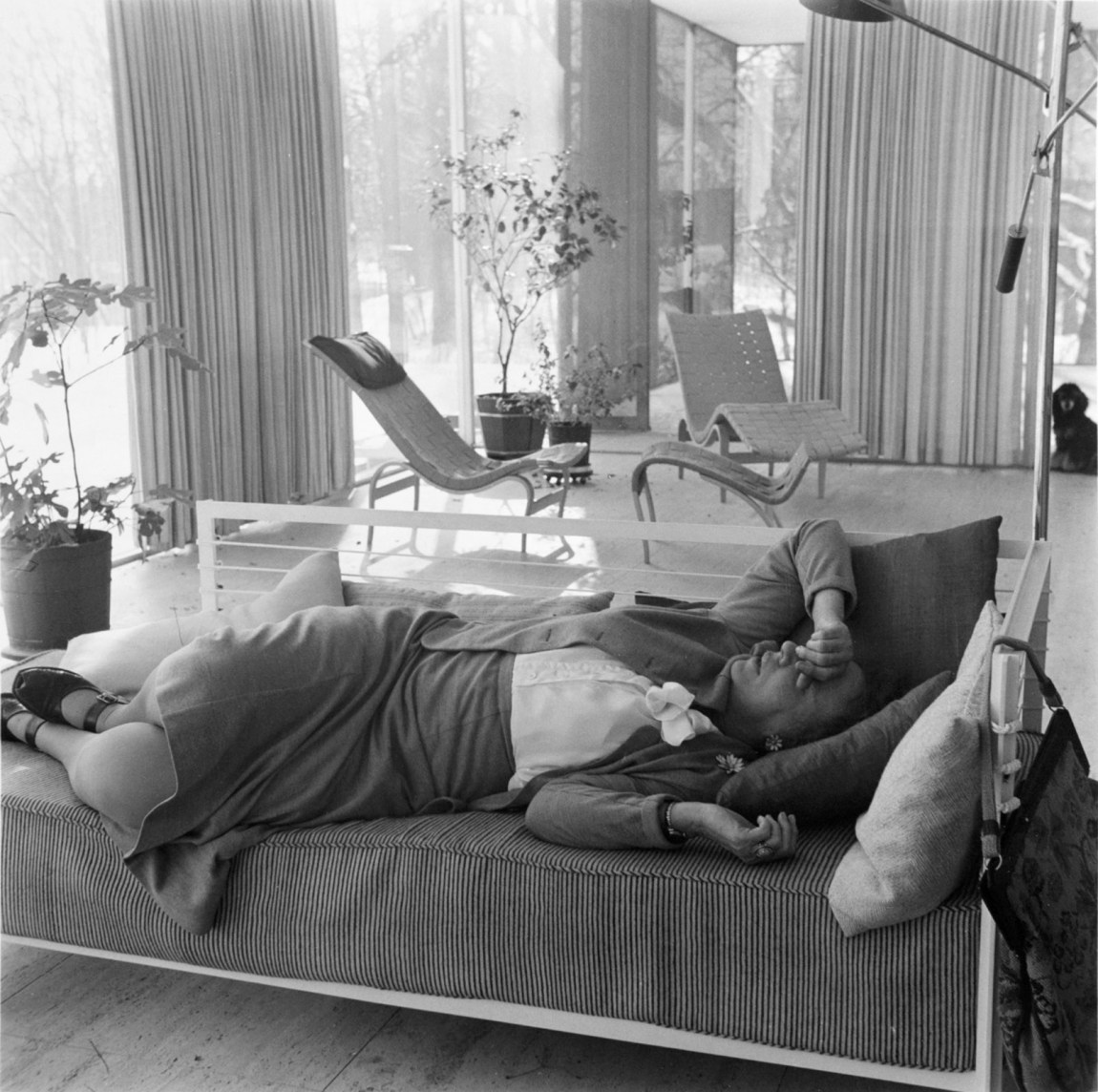

Tangible evidence of Farnsworth’s more positive reevaluation is on view at the Farnsworth house, where the structure’s barely defined open-plan interiors have been temporarily refurnished in an evocation of the relaxed décor she devised contrary to Mies’s wishes. Informed by period photographs of the house taken during her years there, curators approximated Farnsworth’s attempts to soften its hard edges as she simultaneously tried to uphold the fundamental Modernist principles that drew her to Mies in the first place.

In contrast to the chilly machine aesthetic associated with the International Style, Farnsworth’s decorative taste gravitated toward Scandinavian Functionalist interiors of the 1930s and 1940s by such architects as Alvar Aalto, Arne Jacobsen, and Finn Juhl. While she owned it, the house featured interwar Nordic furniture classics including Bruno Mathsson’s bent-beechwood Pernilla chaise longue—distinguished by its springy, gazelle-like outlines—and a similar lounge chair by Jens Risom. These curvaceous forms were complemented by rough-textured Moroccan rugs, an imposing Tang Dynasty ceramic horse, WASPy family heirlooms, houseplants galore, and, on the broad travertine-paved terrace, a pair of Chinese marble “foo dog” (actually lion) sculptures. The warm aura established by Farnsworth—who favored organic materials and sinuous lines, all in an earthy palette of off-white, beige, brown, ochre, and green—was completely different from the mechanistic precision of Mies’s glass, steel, and leather furniture. It was likewise antithetical to the stringent consistency that Philip Johnson achieved in his contemporaneous and more celebrated Glass House of 1945–1949 in New Canaan, Connecticut, a bald-faced plagiarism of the as-yet-unbuilt Farnsworth house (the plans for which Johnson saw in Mies’s Chicago office soon after they were devised); Johnson furnished his house with sparse quadratic arrangements of Mies’s pieces.

3.

Mies’s preconstruction estimate for the Farnsworth house was $40,000 (around $475,000 in current value), but costs are difficult to predict with experimental architecture, and when the total ballooned to $79,000—a 97.5 percent increase—the client refused to pay the architect, who in 1952 took her to court to collect the difference. She countersued, claiming that the house was unlivable because he was incompetent. During the six-week legal proceeding Farnsworth dismayed her friends by lying under oath at least twice. When she asserted that she’d never been shown blueprints for the house, one of Mies’s attorneys inconveniently produced a photo of her and the job captain as they examined plans for the kitchen. She also falsely insisted that she’d not been apprised of escalating costs: a 1950 Mies office memo, titled “Increase in Cost and Informing Dr. Farnsworth,” recorded that by then the estimate had risen to almost $68,000. As the project architect, Myron Goldsmith, wrote at the time, “Mies had great difficulty in telling Dr. Farnsworth but when he did, I think we were very surprised that she took it calmly.”

After much embarrassing publicity for both plaintiff and defendant, the case was decided in Mies’s favor. He never again communicated with Farnsworth once he received her $2,500 settlement check four years after the trial ended. The amount was far less than the nearly $13,000 plus court costs that the adjudicator recommended he receive, but the architect accepted it, one suspects, just to end the ordeal. She continued to decry the house’s many functional deficiencies, especially its lack of air conditioning (something she might have demanded at the outset) and its heedless siting on a floodplain, which led to repeated water damage. Nonetheless, she kept it for another decade and a half, until a new bridge brought traffic close to her live-in vitrine. She then sold it to the British property developer Peter Palumbo, who painstakingly restored it and used it as a vacation retreat until 2003, when a group of Chicago donors gave it to the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

At the end of the 1960s, Farnsworth had a dispute with administrators at Northwestern University Medical School, where she taught nephrology, and also locked horns with a powerful faculty member, the notorious right-wing bigot Dr. Loyal Davis, Nancy Reagan’s adored stepfather, which prompted her to retire from medicine at age sixty-five. Now her long-cherished literary ambitions came to the fore. With the proceeds from the sale of her Mies house she bought the fifteenth-century Villa le Tavernule in the hills south of Florence. According to the critic Giorgio Delia:

Attracted by Italy, chasing the myth (very dear to the Anglo-American culture) of Florence, perennial cradle of the Renaissance, she settled there in the hope, perhaps the illusion, of constituting, or becoming part of a coterie of writers and intellectuals.

This she intended to do by translating Italian literature into English and acting as a scout for Regnery, the Chicago publisher known for its books on right-wing politics, including titles by William F. Buckley Jr., Whittaker Chambers, Robert Welch (founder of the John Birch Society), and more recently Dinesh D’Souza, Laura Ingraham, and Donald Trump. Regnery was a good match for her conservative views. As an American friend recollected, “She was quite paranoid that the Italian Communists were trying to steal her water supply. She thought the American government was full of Communists, too.”

In a pattern that perhaps began with her early mentor Mario Corti, Farnsworth developed a professional crush on Eugenio Montale, a leading figure on the Florentine literary scene, as she translated his poetry. His international fame soared when in 1975 he won the Nobel Prize in Literature, and her obsession with him soared too. As with Mies, she soon imagined that he reciprocated her feelings. “He’s in love with me, can’t you see that?” she insisted to one friend, who later commented, “I couldn’t see it at all.”

The widower Montale encouraged Farnsworth, maybe inadvertently, when he wrote to her, “I just want to tell you that I CARE DEEPLY FOR YOU and that I am so grateful that you exist,” but behind her back he was scathing. “Farnsworth is too remote and rants too much, with much derision,” he reported to a colleague. “She thinks she is a great violinist.” Yet the starstruck American remained oblivious to reality and gushed to her sister, “Imagine meeting your soul mate at my age!”

What Farnsworth called “my tired and depressed life” ended in 1977 at age seventy-four after a brief illness. She was buried in Chicago’s Graceland Cemetery next to her parents, just a few hundred feet away from her architect.

In 2010 a play about the pair, June Finfer’s Glass House, was staged at New York’s Public Theater to tepid reviews. And last year The Hollywood Reporter announced that Farnsworth House, a biopic to be directed by Richard Press, had begun preproduction. Ralph Fiennes was cast as the architect, with Elizabeth Debicki set to play his client. One can be fairly sure, however, that the filmic Farnsworth House will not focus primarily on cost overruns, internal heat buildup, lack of storage space and privacy, or other practical problems of occupying Mies’s human terrarium, but rather on the all-too-human ambiguities that make its creation such an archetypal love/hate story.

-

1

See my “Wright in Love,” The New York Review, November 20, 2008. ↩

-

2

Reich died there in 1947 and Mies’s wife in 1951. Their youngest daughter, Waltraut, a curator at the Art Institute of Chicago, died in 1959, aged forty-two. The two others survived Mies, who died in 1969 at eighty-three: Marianne (mother of Mies’s architectural collaborator Dirk Lohan) lived until 2003, and the eldest, Dorothea (an actress known as Georgia Herterich) died six years later in Berlin at ninety-four. ↩

-

3

Thresholds, No. 43 (2015). ↩

-

4

See my “Building and Nothingness,” The New York Review, June 12, 1986. ↩