At the end of The Gift, a memoir of H.D.’s American childhood unpublished in her lifetime, she appends a chapter set in the present, London, 1943. An air raid takes her household by surprise, and she describes what it’s like in her fifth-story flat in Lowndes Square with “terrific shattering reverberations of the great guns.” Annie Winifred Ellerman, her partner (better known by her pen name, Bryher), switches off the lights, closes all the doors, and turns on a small lamp only after the blackout curtains are drawn:

The noise was so terrible now that I could not hear what Bryher was saying, but she was saying something. She got up from her chair and took a few steps across the red and grey patterned rug and she stood by my chair. I did not move. The chair would go down too, as if we were both in a lift, an elevator, and we would keep on going down and down. But now the floor was level and I was not going down.

But she did go down—very deep, in fact, into the past, into her psychic depths, for the final chapter makes it clear that proximity to death opened a creative vein.

Hilda Doolittle was born in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, in 1886 and died in Zurich in 1961, but for the duration of both world wars she was a Londoner—barely even leaving the city for the comparatively safer countryside. The first war was a personal, a psychic, catastrophe: she lost her father, her brother, and a baby—after which her marriage foundered. The second war brought on a creative storm. She wrote The Gift, dedicated to her mother; Tribute to Freud, with whom she had undergone analysis in the 1930s; and three long poems collected under the title Trilogy, sometimes referred to as her “war trilogy.”

“The past is literally blasted into consciousness with the Blitz in London,” she wrote in 1944. It was frightening but overwhelmingly euphoric. Writing to May Sarton about Virginia Woolf’s suicide, she couldn’t believe that Woolf would turn her back on the world “just when…one longs to be able to live to see all the things that will be bound to happen later…. Times were NEVER so exciting.” As she wrote in The Gift:

It had been worthwhile. It had been worthwhile to prove to oneself that one’s mind and body could endure the very worst that life had to offer—to endure—to be able to face this worst of all trials, to be driven down and down to the uttermost depth of subconscious terror and to be able to rise again.

The scene in her apartment as the bombs dropped has the mood of a séance—dark room, dim lamp, the anticipation of doors flying open, “pushed out by the repercussion of the blast.” All her life, in addition to her devotion to poetry and ancient Greek, H.D. maintained a fascination with the occult: astrology, tarot, spiritualism. After attending lectures on mediumism by Hugh Craswell Tremenheere, Lord Dowding, an RAF officer who helped win the Battle of Britain (he claimed to have communicated with his dead pilots), H.D. started pestering him with letters asking to join his “circle.” Having been rebuffed several times, she insisted that she too was hearing from RAF casualties. Not long after the war ended, she had a total physical and mental collapse and was sent to a Swiss sanatorium.

In her 1984 biography of H.D., Herself Defined, Barbara Guest vividly imagines a scene in the British Museum tearoom in 1912: Hilda Doolittle shows her new poems to Ezra Pound, who, enthralled, invents Imagism on the spot. He singled out her poem “Hermes of the Ways” and signed it with her new nom de plume: “H.D. Imagiste.” “Would that today the excised poem with its corrections might rest in the Berg Collection in New York,” Guest writes, “alongside Pound’s similar selective corrections and deletions to ‘The Waste Land’ of Eliot.”

Guest’s intention was to restore H.D. to the first rank of modernist poets, just as H.D. worked to restore the female figures of myth to their rightful place at the center of our oldest stories. H.D.’s poetry eschews colloquial realism—or, as her acolyte Robert Duncan put it, respectability. It creates a closed world. It demands a certain comfort level not only with the personae of Greek poetry but with Celtic and Egyptian religion, Christian saints, heresies, and cults. (Hermes Trismegistus, anyone? Mithra’s tomb?) You could say that Eliot and Pound got away with myth and anachronism; Stevens created closed worlds too. H.D. goes all in for hermeticism. It was she whom William Carlos Williams was thinking of when he wrote in his preface to Kora in Hell, “Hellenism, especially the modern sort, is too staid, too chilly, too little fecundative to impregnate my world.”

Advertisement

It’s true. H.D. doesn’t sound modern—she sounds timeless. While one of the ironies of modernist verse was that much of it was archaeological in method—think of Eliot delving into The Golden Bough or Pound excavating Greek lyric—H.D.’s version doesn’t let in the rank air of the industrial city, twentieth-century politics, contemporary vernacular. It eschews pathos and, at least in the Imagist poems, evokes something languid and passive, subject to the assaults of pagan nature:

Fruit cannot drop

through this thick air—

fruit cannot fall into heat

that presses up and blunts

the points of pears

and rounds the grapes.

And yet it is this poem, “Heat,” recited by a schoolteacher—one Miss Keough, in 1930s Bakersfield, California—that electrified a teenage Robert Duncan and showed him his vocation; he worked on a poetic treatise titled The H.D. Book for almost thirty years, trying to account for her lyric power. The rhythmic force of H.D.’s spare and sensual poems was learned from Emily Dickinson, the Pre-Raphaelites, and the Greek Anthology. If it appeals primarily to initiates, no matter: there are enough of the initiated through the ages to recognize one of their own.

The great salutary effect of reading H.D.’s novels and memoirs—many brought out late in life or posthumously—is to restore her to her era. For all her intense communing with the past and other worlds, it is this dimension, the extraordinary life lived in extraordinary times, that captivates. It is something to have been at the vanguard of early-twentieth-century poetry and film in London: an analysand of Freud’s, a friend of Havelock Ellis and D.H. Lawrence, and, frankly, the lifelong kept woman of a (female) English millionaire.

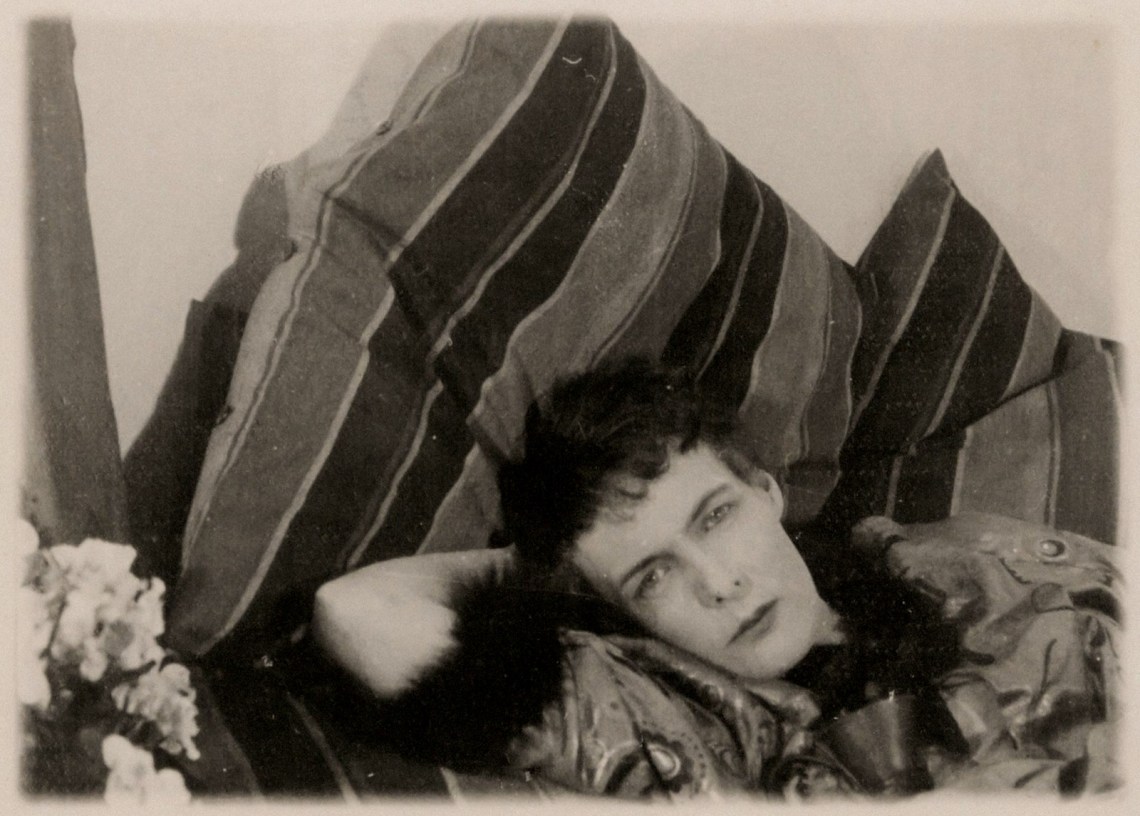

It all could have been otherwise: she was born the daughter of an astronomy professor at the University of Pennsylvania. (Her mother was a pianist who had given up her vocation when she married.) As she recounts in The Gift as well as HERmione, a roman à clef of her youthful love triangle with Pound (to whom she had been briefly, and ambiguously, engaged) and her lover Frances Gregg, H.D.’s upbringing was in many respects stifling. A woman of striking beauty (even the camera captures it), she was made to feel too tall, too intense; she stooped and adopted a pose of diffidence. Pound was instrumental in freeing her from her parents and fastidious Bryn Mawr and blasting her to Europe.

It’s one of the most riveting stories in American poetry: they met at a Halloween party in 1901. She was fifteen, from Upper Darby; he just sixteen, from nearby Wyncote but already a first-year undergraduate at Penn. He had “Gozzoli bronze-gold” curls and wore a green Tunisian robe, every inch the flamboyant troubadour the world would come to know. In HERmione, Pound’s alter ego George Lowndes is forever entwined with the color green, and green with Pennsylvania: when he makes love to Hermione Gart she imagines the room is a bower of moss and trees. (H.D.’s “first kisses” were with Pound in the woods.) Both George and Pennsylvania are immersive and ambivalent and threatening:

“This is the forest primeval, the murmuring pines and the hemlocks,” (George intoned dramatically; she knew why she didn’t love him) “bearded with moss and with garments green, indistinct in the twilight.” She knew why she couldn’t love George properly. George gone tawny, hair the colour of vermillion seaweed, wash of vermillion over grey rocks, the sea-green eyes that became seagrey, that she saw as wide and far and full of odd sea-colour, became (old remembered reincarnation) small and piglike. George being funny is piglike. His eyes are too small in his face. His teeth are beautiful but when he is being funny he unnerves one. George back of George, George seen through a screen door, George gauzed over by lizard-film over wide eyes, George seen with perception was wavering tall and Gozzoli-like with green jerkin. Almost this is the forest of Arden.

Here H.D. creates a thicket of prose, looping with repetitions like a lost person walking circles in the woods, to imitate the claustrophobia she feels: “Pennsylvania had her. She would never get away from Pennsylvania.”

Yes and no; her destiny was Europe, but it was Pound who drew her there; she distanced herself from him (and his politics) but kept him in her orbit; she accepted his nickname for her, Dryad, and when late in life she wrote a memoir of him, End to Torment, she appended to it Hilda’s Book, the poems he wrote for her between 1905 and 1907. As excruciating as any teenager’s love poetry but notable for its Petrarchan pastiche (after all, this is Ezra Pound), Hilda’s Book gets one thing absolutely right: in “The Tree” he laments that they could have been the faithful couple Philemon and Baucus, whom Apollo turns into two trees to keep them united after death; instead H.D. chose to be Daphne, his ever-elusive laurel.

Advertisement

In H.D.’s novel, George Lowndes calls her Undine, not Dryad; the undine is a water sprite, and H.D. was rightly afraid of submerging her identity in his. (He “would have destroyed me and the center they call ‘Air and Crystal’ of my poetry,” she wrote in End to Torment, hence the broken engagement.) But there was a similar danger in her other affair, with bisexual Frances Gregg—Fayne Rabb in HERmione. The trancelike rhythms and repetitions of the sentences immerse the reader in the febrile, obsessive quality of adolescent passion:

Words with Fayne in a room, in any room, became projections of things beyond one. Things beyond Her beat, beat to get through Her, to get through to Fayne. So prophetess faced prophetess over tea plates scattered and two teacups making delphic pattern on a worn carpet. Pattern of little plates, of little teacups (Fayne as usual had had no lunch) and people and things all becoming like people, things seen through an opera glass. The two eyes of Fayne Rabb were two lenses of an opera glass and it was Hermione’s entrancing new game to turn a little screw, a little handle somewhere (like Carl Gart with his microscope) and bring into focus those two eyes that were her new possession. Her Gart had found her new possession.

Gregg was also a would-be writer, two years older than H.D., extremely thin with piercing blue eyes and a boyish beauty. They met shortly after Pound left Philadelphia for Europe in 1910, leaving a gulf in H.D.’s emotional life that Gregg quickly filled as a long-desired feminine twin-self. (H.D. had five brothers but no sisters.) When Pound returned, he scoffed at their liaison, calling them witches, yet an “explosive three-way entanglement ensued, with Frances falling in love with Ezra and H.D. continuing to be in love with both of them.” H.D.’s parents sent her to New York to force a separation from Gregg, but after five months H.D. returned, and both women, supervised by Mrs. Gregg, set off on the ocean liner Floride to join Pound in London.

HERmione, like many of H.D.’s works, is a game of names. As a stand-in for Hilda, Hermione refers to the Shakespearean heroine who is the victim of tyrannical passions, and when shortened to “Her” becomes anonymous and amoebic—a pronoun in search of an identity. Alluding to a lesbian code of “wild hyacinths” in a climactic moment of the novel, Hermione sees Fayne’s love as a trap: “I will be caught finally, I will be broken. Not broken, walled in, incarcerated. Her will be incarcerated in Her.” The genius of that mimetic, palindromic line—will walled in by two Hers—pivots on the multiple meanings of “will”: if a verb, the first Her is a subject and the sentence grammatical; if a noun, it turns passive and the grammar falters into a fragment.

In London Pound introduced the women not only to literary society but to their future husbands. And thus another chapter began. Donna Krolik Hollenberg’s new biography, Winged Words, divides H.D.’s life into neat chapters, a grid in which to contain a many-faceted subject: marriage to the fellow poet Richard Aldington, World War I, a stillbirth (in the 1910s); separation, pregnancy with another man’s child, and alliance with her partner and benefactress Bryher; a further affair with the bisexual filmmaker Kenneth Macpherson and the various ménages that ensued (in the 1920s); Freudian analysis in the 1930s; World War II and prolific literary output thereafter, in London and then Switzerland, where Bryher sent her to recover from the war.

This is a very bare outline of a very tangled interpersonal web. Like that other well-known literary cluster in Bloomsbury, with which H.D.’s circle sometimes overlapped, everyone loved in triangles, if not quadrilaterals. One of H.D.’s best novels, Bid Me to Live, offers a fictionalized account of the lively and painful games they played circa 1917, when she gave permission for Aldington, who was frequently away on military duty, to pursue an affair. She found it agonizing, but when a couple shows up—D.H. and Frieda Lawrence in real life—she is drawn into their force field and into creative battle with Lawrence. Like HERmione, it’s a bit of a highbrow potboiler.

In both books, it’s notable that eros is essentially a conduit to one’s own genius. These recognizable types argue monstrously, smoke, drink, talk in circles, and drive one another crazy with opacity in the guise of—forgive the buzzword—transparency. Less looping and repetitive than HERmione, Bid Me to Live offers some of H.D.’s sharper observations, with descriptions of Lawrence verging on sunburnt satyr or smiling werewolf, while his wife looks on “with the justifiable pride of a barn-yard hen who has hatched a Phoenix.”

But readers, not satisfied with fiction, will want to know the ins and outs of a creative woman’s life. How did H.D. manage to be a mother and so prolific and also drift through various fascinating entourages? The answer of course is money—Bryher’s money. When H.D.’s marriage to Aldington faltered, she sought comfort in Cecil Gray, a musician and writer in their circle, and ended up pregnant. Bryher muscled Gray aside and adopted the child, Perdita, after marrying Robert McAlmon, another bisexual writer, for appearances. Perdita, now surnamed McAlmon, was thus saved from illegitimacy and also had the benefit of two mothers—one who was high-strung, poetic, and often unavailable, and another who managed her upbringing.

Bryher did not endear herself to everybody; she was autocratic and manipulative, and undoubtedly her adoption of Perdita was tactical. She was possessive of H.D., though the sexual aspect of their alliance was short-lived. Nor was she a muse: H.D. did not write about Bryher in the highly charged way she wrote about Gregg, Pound, or D.H. Lawrence. They only once cohabited over an extended period. Mostly they led separate lives, but they never parted ways: Bryher’s wealth and belief in H.D.’s genius proved stabilizing. Without Bryher there would have been no H.D. as we know her today.

The many details I must gloss over for brevity’s sake can be found in Hollenberg’s dogged, academic biography, but readers looking for an electrifying narrative should seek out Barbara Guest’s Herself Defined. One of the problems with Hollenberg’s flavorless prose is that it is unable to convey sympathy—either as advocate or as skeptic—and one needs a helping of the biographer’s good faith to accept some of H.D.’s dottier theories and practices. She looked at herself as a “hieroglyph” to decode, and this led her to obsess tediously over dreams and sigils—images such as a serpent wrapped around a thistle, or a “jelly-fish experience” relating to a “womb-brain.”

There are the séances and rapt attention paid to tarot and astrology, attempts to reconcile “feminine” and “masculine” aspects of identity through mystical projections. Pages and pages of speculation in Hollenberg’s affectless account feel tendentious and inconclusive and ultimately vapid. In the chapter dealing with H.D.’s analysis in Vienna, Hollenberg gives us, poker-faced, one psychoanalyst’s account of writer’s block as a dancer’s “magic phallus”: “The dancer is frozen in terror at her unconscious hatred of her mother and desire to have what her mother had, ‘from milk to children and the father’s penis.’” I was unconvinced.

Guest, with greater fluency and immediacy, traced H.D.’s mysticism to her childhood as a Moravian Christian, the descendant of a pacifist sect that originated in Bohemia in the fifteenth century. (The poet-philosopher Novalis was also one; H.D.’s poetry can sit comfortably beside his.) The persecuted Moravians, led by Count Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf of Saxony, found sanctuary in Pennsylvania, naming their settlement Bethlehem. For her first decade, in the constant company of close kin and fellow churchgoers, H.D. was cocooned in a way of life that organized itself around symbols and found expression in music especially. (Thomas Mann details the musical practices of Pennsylvanian Moravians in a spellbinding passage in Doctor Faustus.) When her father took a job as the director of the Flower Observatory at Penn, she was jettisoned from the magic circle in Bethlehem to a drab and secular suburb.

Sometime between 1949 and 1951, H.D. wrote about Zinzendorf and his followers in The Mystery, a bridge work between her wartime books and her late epics, Helen in Egypt and Hermetic Definition. The war—though it eventuated her removal to a Nervenklinik—proved more of a wellspring than eros had ever done. It led her back to her childhood and a renewed appreciation of her origins, especially her mother; it returned her to her mother’s religion and its avowal of universal love and peace. It provided the stimulus for the most interesting idea for poetry that she ever had: an epic about Helen, not Homer’s Helen but Euripides’ and Stesichorus’s Helen, the one who was spirited away to Egypt to wait for her husband’s return from the Trojan War, whose rumored liaison with Paris never happened, who was slandered and never served as the occasion for bloodshed. Stesichorus’s palinode—that is, a counter or negation of a previous ode—could be the perfect emblem for H.D.’s poetry, or any woman’s poetry effecting historical reversals.

Helen, as it happens, was her mother’s name. Like Bethlehem, it had personal as well as mythic significance. H.D. was trained early on, by religion and by music, to spot correspondences and to look beyond appearances, as she wrote in an early story: “Behind the Botticelli, there was another Botticelli, behind London there was another London…” Echoing this thought later, in HERmione, she rhapsodized:

She did not know that Pennsylvania bears traces of a superimposed county-England and of a luscious beauty-loving Saxony. She could not know that the birdfoot violets she so especially cherished had far Alpine kinsfolk, that the hepaticas she called “American” grew in still more luminous cluster at the base of the Grammont, along the ridges of the Jura, in rock shelves above Leman and the Bodensee.

Of this poetic, perceptual, historical way of knowing, less mystical than simply highly attuned, I was, yes, completely convinced.