“Poetry,” Ida Vitale remarks in the essay included in her new collection, “like death, perhaps, is surrounded by explanations.” Now living again in Montevideo, Uruguay, where she was born in 1923, Vitale can take poetry’s prestige for granted. Over the past century or more Latin America has commanded a world stage: the writings of César Vallejo, Jorge Luis Borges, and Pablo Neruda, among others, hardly require explanation or defense. Her own cohort, the Generation of 1945 (the “Generación Crítica”), was instrumental in keeping Montevideo abreast of cosmopolitan developments in literature, theater, and critical theory. Vitale has received numerous prizes in Uruguay, Mexico, Spain, and France, as well as the rank of Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters of France in 2021. Yet her first selection of poems in English translation (over seventy years’ worth of work, presented in reverse chronological order) contains just one brief manifesto, “Poems in Search of the Initiated,” registering a delicate protest against the diminished readership for poetry:

The challenges awaiting a less confident reader may include unusual verbal constructions, not worn out by use, and a richer vocabulary. These are not impossible to face. The pleasure of enthusiastic decipherment releases a mysterious energy that moves not only the pages of poetry, but also the world’s great prose.

Mystery, Vitale notes, is “that which is reserved for the mystai, the initiated,” and “on the other hand…leads us to the idea of ministry.” But in a democratic age—or, more accurately, an age when democracy is teetering toward authoritarianism—“the initiated” evokes the specter of an elite despised on all sides: “rarefied poetry for the few, almost for specialists.”

Vitale rejects this charge. In addition to poetry, she has published essays in newspapers and journals, taught and translated, served on international prize juries and conference panels in Cuba and the Soviet Union. “Her personal political leanings,” writes her translator, Sarah Pollack, “aligned with those of the Uruguayan Communist Party until the beginning of the 1970s.” After the 1973 coup that installed Juan María Bordaberry in a military dictatorship, she and her second husband, the poet Enrique Fierro, went into exile in Mexico City for ten years. They returned to Montevideo when the dictatorship fell, and from 1990 to 2016 resided in Austin, Texas, where Fierro taught literature. Vitale’s peripatetic life has yielded a worldly and philosophical body of work.

If she senses that poetry needs an apologia, it is not because her poems are particularly hermetic. Take this poem from her 2002 collection, Reducción del infinito:

Sums

horse and horseman are already two animals

—J.D. García Bacca

One plus one, we say. And think:

one apple plus one apple,

one glass plus one glass,

always equal things.

What a difference when

one plus one is a Puritan

plus a gamelan,

a jasmine plus an Arab,

a nun and an escarpment,

a song and a mask,

once again a garrison and a maiden,

the hope of someone

plus the dream of another.

This is a poem about errancy and abundance, treated with a light, even buoyant touch. The assortment of Puritans, gamelans, Arabs, and nuns should make us smile, perhaps reminding us of another exuberant poet who delighted in noun pileups: the Wallace Stevens of “People are not going/To dream of baboons and periwinkles” in “Disillusionment of Ten O’Clock.” The particulars of the world are multiple and irreducible, but because these aren’t equal things, one person’s hope has an uneasy relation to another’s dream.

What starts out with arithmetic simplicity and certitude slips in a very short space into complexity and negotiation. For, as Vitale notes in “Dream,” “dilemmas are reborn in dreams.” In her afterword Pollack writes:

Unlike many of her Latin American contemporaries whose poetics are associated, however reductively, with various trends and movements like the avant-garde, colloquialism, political poetry, (feminine) subjectivity, or eroticism, Vitale’s singular writing…doesn’t fit so neatly into a single category.

But isn’t it the fate of the nonindigenous poet in the western hemisphere to be acutely aware of her own mongrelism—in life as in art? Descended from Sicilian immigrants, Vitale writes:

Sicily, the Trinacria,

unknown source

with three capes:

I will die

without taking dark memories

to your land…

Arabs and oranges

and songs

and ruin….

This “unimaginable/destiny/transgressed” provides the negative capability out of which her poems spring. In “Exiles” she writes:

They’re here and there: passing through,

nowhere really.

Every horizon: wherever an ember beckons.

They could move toward any crack.

There is no compass, no voices.

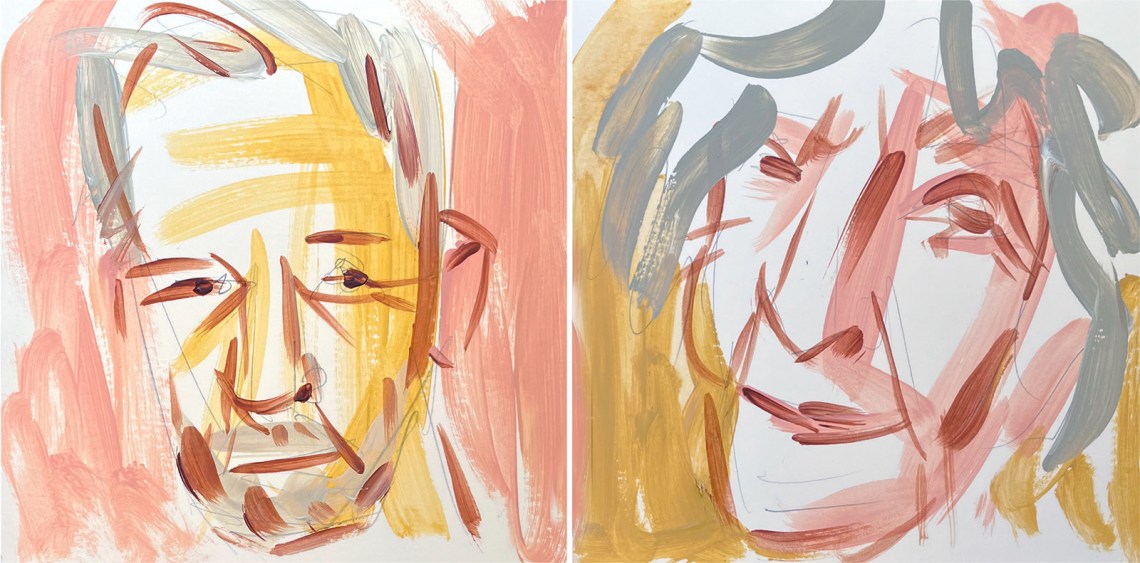

Vitale’s expatriate imagination gravitates toward avian metaphors. (Her author photo, taken by her daughter, Amparo Rama, shows her with a songbird perched on her finger, her wizened figure alert and birdlike in a garment whose pattern suggests a Cretan labyrinth.) In “Nostalgia for the Dodo,” she writes, “Yes, I’m nostalgic for the dodo, and more,/for the countless extinctions it condenses.” In “Falconry,” a word “is wandering around lost/like a young bird, without a nest yet,/without center or argument/or spell on which to land.” Mockingbirds, doves, grackles: they paradoxically define an environment and exemplify the principle of migration. A poem itself is a kind of “paper bird,” “miraculous origami,/paper feather-light,” that survives by traveling long distances by instinct, the unfolding of an inner map. Even the phrase “miraculous origami” (“origami milagreado”) enacts its own implications (from the Latin implicāre, “to fold about itself”), with its repetitions of ri/mi/mi/, ga/grea, bracketed by open o’s.

Advertisement

Vitale’s poems are short—rarely more than a page or two—as if, having perched for a moment on our attention, they have determined not to overstay their welcome. Their ludic play, as we see with “origami milagreado,” combined with a light (gentle, not jovial) tone, returns us to the concerns evident in her essay: “The allusiveness, the metaphors, the nuances” that poetry offers “require more mental effort. Imagine the work gymnasts dedicate to their bodies to master them satisfactorily! Mastering that ambitious form of language also has its rewards.”

“Mystery,” my dictionary reminds me, also carries an obsolete English meaning of handicraft or trade. Vitale’s poems aren’t mystical effusions; they are made things. She may overstate it when she says that poetic devices “require more mental effort”; the key, rather, is openness to experience. I keep going back to her author photo, a modern sacra conversazione, with that one finger (dactyl) proffered for the bird’s (poetic) feet—encapsulating her plea for patient readers.

Halfway across the globe in Opole, Poland, Tomasz Różycki has related concerns: “Meanwhile, there aren’t enough seats/for so many authors who hope/to get noticed by the one and only Reader tonight.” That’s the ironic set-up of “First Crisis of the Reader,” an imaginary book tour in which it is the reader—perhaps the last reader left—who is besieged by a throng of competing writers. The reader has all the power: “Reading—he smirks—should be done rarely/and reluctantly.” This send-up of our cutthroat era of overproduction is very much of a piece with the poetry of his Slavic predecessors—Zbigniew Herbert, Wisława Szymborska, Adam Zagajewski, Joseph Brodsky:

And aren’t I losing writing, losing conversation,

word after word, right now? In art, it’s easy

to shine—too easy to become state champion.

The elusive reader may also be a stand-in for the other absent witnesses to a life—dead parents, expired gods. “I wish you were here” is a refrain in the book, drawn from poems by Brodsky and Stanisław Barańczak but most familiar to our ears from Pink Floyd’s rock classic—Różycki, his translator Mira Rosenthal once said, synthesizes New York School urbanity and Eastern European gravitas.

Irony is the spice of poetry. Herbert’s renowned “From Mythology” imagined a tribe that carried statuettes of salt in their pockets, representing “the god of irony.” Różycki’s irony can be caustic (“some people are so poor the only thing they have/is money, money”), or it can be sublimely political:

At last, a fifth wave tips the boat of refugees

into the Mermaid Bay, today so murky,

and the ocean, with its love of children, takes them

on an odyssey, to lay them down in the end

on the sands of Lampedusa, Ithaca, Avalon.

This time, the gods and goddesses keep watch

discreetly on their monitors in split display.

They cheer them on, these Greek and Trojan castaways.

But when one god, from boredom, clicks the channel,

it tips the scales, and then the sea eternal

brings someone back to life on a rocky beach.

Now he sits behind barbed wire, near the freeway,

chewing dry bread and waiting for asylum

to be granted in the land of Latium…

Here, classical references are turned on their head: the refugees from devastated Troy (in contemporary Turkey) who went on to found Rome are contrasted with today’s refugees from North Africa and the Middle East; the Sirens who beckoned ships toward destruction in the Odyssey live on in “Mermaid Bay”; when the fickle gods save someone from shipwreck, he isn’t greeted, like Odysseus, by a solicitous Nausicaa, although the land’s “daughters of fire-red hair descend,/they say, directly from the horned god Faunus.” Faunus, the Roman variant of the Greek god Pan (“all”), supposedly derives his name from the word for “merciful.”

Różycki was born in 1970 in Opole, where his family was resettled after displacement from Lwów following World War II, when the borders of Poland and Ukraine were redrawn. He is now the leading poet of his generation, and To the Letter is his latest book to be rendered into English. Rosenthal, who has been translating Różycki for two decades, writes that his family “kept pre-war Lwów alive in idealized memories, a kind of mirror world.” His poem “Mirror” seems to speak directly to the experience:

Advertisement

A throw of dice can easily upend one’s luck,

just toss them long enough, isn’t that right?…

Perhaps an epoch

is not quite long enough, nor a single lifetime,

for pattern and order to emerge from numbers.

Better to look from far away….

Indeed, from this distance—well into the twenty-first century—a pattern of uprooting does emerge, looking more and more impersonal. Różycki, who has taught French literature and translated Mallarmé’s Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard, takes in stride the new metaphysical order ushered in by physics and statistics in such poems as “White Dwarf,” “Vacuum Theory,” and “Chaos Theory.”

After all, one need only glance back at Vitale’s “Exiles” to apprehend in an instant how commonplace this condition is. Her paper birds could be poems or passports; Różycki’s bird in “The Crisis of the Polish State” is a migratory thrush that encompasses Europe:

But think what kind of route

it’s flown to end up here—past those depraved

hunters of birds in the groves of Cyprus, past Russian

fighter jets in Syria, dioxin clouds above Ploesti,

the pesticide-polluted Danube, tainted waste by the tons

in forests lining the Oder—through all this debris

just to soar over to Poland, where a rubbish faction

has just sprung up in Warsaw.

To the Letter was written in 2015, the year of a parliamentary election won by the right-wing Law and Justice party, and Różycki’s thrush serves as a warning:

So, thanks for coming and

proclaiming your dominion with such amorous

song in the night above this boggy land

where Jews have vanished.

And as a Polish Keats might say to his nightingale: “Count me among your serfs.”

The book’s Polish title, Litery, means “letters”; Rosenthal’s decision to translate it as To the Letter is a nod to the playfully recursive nature of Różycki’s lyric metaphysics. The idiom in English suggests a fine punctilio, dotting one’s i’s and crossing one’s t’s; but if your alphabet has nine letters with diacritical marks, then this exactitude grows antic, sprouting metaphors. “In the Cave” asserts “our mongrel love, not for a people but a language/of marks, cascade of consonants, signs of incongruity.” And “Squiggle,” dedicated to Brodsky, dwells ruefully on an alphabet that “has grown a whole cluster/of tails…/the bristles they grow, how they wake up pregnant”—alluding to Brodsky’s “A Part of Speech,” in which “when ‘the future’ is uttered, swarms of mice/rush out of the Russian language and gnaw a piece/of ripened memory which is twice/as hole-ridden as real cheese.”

“An Act of Speech” is also a Brodsky homage. Where Brodsky wrote, “I was born and grew up in the Baltic marshland/by zinc-gray breakers that always marched on/in twos. Hence all rhymes, hence that wan flat voice,” Różycki responds:

By now it’s clear what I’ve inherited—

this great open plain that suddenly gives way

to the steppe without warning, just beyond

the river, traces of campfires, bottles, charred remains.

To the Letter, then, should also be read as an apostrophe: a love letter to the language, the one remnant of history that a poet, calling on his forebears, need not be ashamed of. Rosenthal deserves special praise for rendering Różycki’s wordplay, musical density, and metonymic dazzle into powerful English:

For who can mold

a string of signs so that even a rolled-up paper

gun can open fire, bringing down the ghost

with a round of explosive sound, a flash of meter?

This reader jumped in her seat. Our famous somatic metaphors for the effects of reading—Kafka’s ax, Dickinson’s trepanned head, Housman’s shaving cut—belie the notion that this is all just mental gymnastics. Like Vitale’s “origami milagreado,” Różycki’s poem as “rolled-up paper/gun” is a handmade, fragile, but potent technology for survival.