1.

Art Nouveau—the phantasmagoric “new art” that emerged in the twilight of the nineteenth century and flourished during the dawn of the twentieth—quickly wrapped itself around the popular imagination with all the tenacity of the winding vines that became its predominant motif. Although it remains one of the oddest and most recognizable manifestations of the Modern Movement, historians have never been able to fully explain its anomalous nature or consign it to a neat place in accounts of cultural “progress.” Now, more than a century after its short-lived heyday, a new generation of scholars is finally offering insights into its varied origins, its far-flung diffusion, and its deeper meanings.

Art Nouveau (a catchall term for the variously named but closely related styles that had a pervasive impact on architecture, painting, and sculpture as well as applied design of every kind, from jewelry and typography to furniture and infrastructure) burst onto the European scene around 1880. Soon its undulating lines, swirling excesses, and propulsive forms could be found everywhere, from the billowing butterfly-like costumes of the avant-garde dancer Loïe Fuller (who at the 1900 Paris Exposition had her own theater pavilion, designed by the eminent Art Nouveau architect Henri Sauvage and crowned with a larger-than-life-size statue of its star attraction) to the Brussels palaces that the style’s most adept architectural talent, Victor Horta, designed for nouveau riche Belgian oligarchs. Its extraordinary applicability, from high art to utilitarian design, was but one of its innovative characteristics. Furthermore, this novel aesthetic caught on so completely because it presented modernism garbed in the raiment of pure pleasure, not the hair shirt of social obligation or moral uplift. It was also more than a bit vulgar and on occasion blatantly sexy, qualities that have never dampened mass appeal.

Implicitly antiestablishment and insinuatingly revolutionary, Art Nouveau spoke to the period’s endemic unease about a new century that would surely be nothing like the old one. The style’s wavering contours conveyed sensations of constant movement, persistent instability, uncertain boundaries, and inevitable change. By the time its popularity began to wane—around 1910, when it was replaced by a reactionary resurgence of Neoclassicism—the globe had been figuratively encircled in its seductive embrace.

Sixty years ago Art Nouveau came to be seen once again as excitingly rebellious by the proponents of a youthful counterculture who emphasized its joyous sensual abandon. That can be discerned in such Sixties favorites as the tornadic ceramic-inlaid architecture of the Catalan Antoni Gaudí, the kinky black-and-white drawings of the British Aubrey Beardsley, the refulgent multicolored glassware of the American Louis Comfort Tiffany, the curlicued bentwood furniture of the Austrian Thonet brothers, and the radical white-on-white interiors of the Scottish couple Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, all of whom again found acclaim after their reputations had languished through decades of posthumous oblivion.

The Museum of Modern Art’s decision in 1958 to permanently install one of the French architect Hector Guimard’s cast-iron Paris Métropolitain station entrances of circa 1900 in its Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden—where the patinated metalwork of its sinuous vegetal forms harmonized perfectly with nearby bronzes by Rodin, Matisse, and Picasso—presaged the worldwide Art Nouveau craze that was about to begin. Undoubtedly the revival was also given a considerable boost by MoMA’s well-attended 1960 exhibition “Art Nouveau: Art and Design at the Turn of the Century,” the first full-scale survey in the US, which brought together more than three hundred objects and later traveled to Pittsburgh, Los Angeles, and Baltimore.

Another hugely influential exhibition of that decade was the Beardsley retrospective that appeared at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum in 1966 and then in somewhat modified form the following year at Huntington Hartford’s Gallery of Modern Art in New York. This fall a smaller but no less exquisite selection of the artist’s works was shown at New York’s Grolier Club to mark the sesquicentennial of his birth in 1872. The seventy pieces in “Aubrey Beardsley: 150 Years Young” were drawn from the collection that the bibliophile Mark Samuels Lasner has given to the University of Delaware and, as the landmark 1967 exhibition also did for me, offered stunning evidence of how much this perversely imaginative and demonically driven genius accomplished in his twenty-five years of life, cut tragically short by the tuberculosis that plagued the entirety of Beardsley’s brief but brilliant career.

One ubiquitous decorative appurtenance of the Love Decade was the Czech Art Nouveau artist Alphonse Mucha’s 1898 poster for Job rolling papers, featuring a Rapunzel-haired temptress holding aloft a lit cigarette that could easily be confused with the joints that were smoked in so many of the dorm rooms where reproductions of this hypnotic graphic hung. It seems no coincidence that a major erotic fixation of the Me Generation was hair—“shining, gleaming, streaming, flaxen, waxen” (to quote the title song from Hair, the 1967 “American tribal love-rock musical”)—as it also had been for many turn-of-the-century artists. One such enthusiast was Beardsley, whose densely detailed 1896 illustrations for Alexander Pope’s early-eighteenth-century mock-heroic poem The Rape of the Lock cloaked hair fetishism in the elaborate fripperies of the Rococo style.

Advertisement

That early-eighteenth-century offshoot of the Baroque was lighter and more playful than its ponderous precursor and is considered Art Nouveau’s closest spiritual antecedent. They were indeed similar in their rhythmic use of lilting S curves and reverse-S curves, as well as their evocation of patterns drawn from the natural world—shells, leaves, boughs, roots, and tendrils—and a shared preference for fully integrated design schemes from the largest scale to the smallest detail.

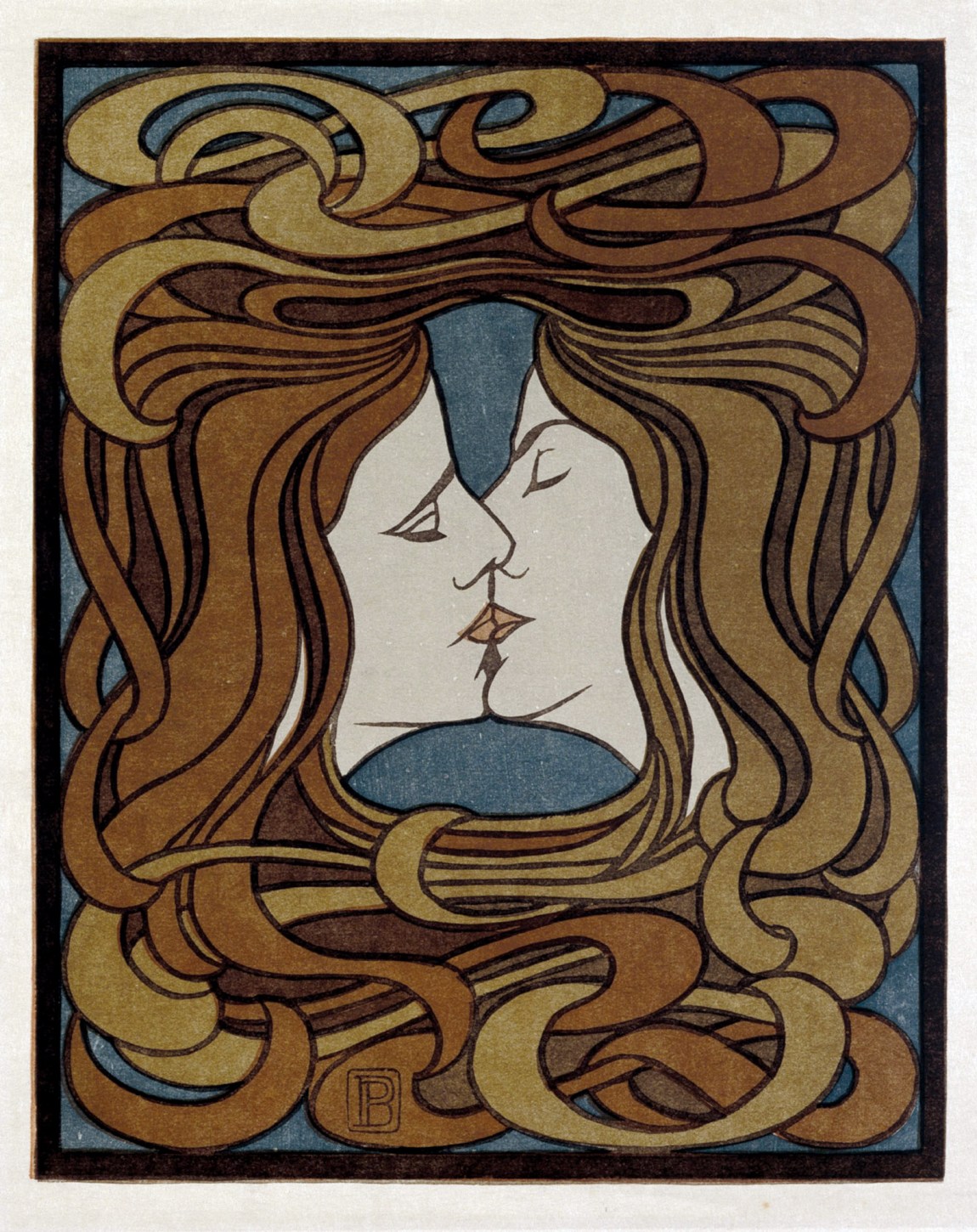

Another celebrant of voluptuous hair was the protean German architect and designer Peter Behrens, whose narcissistic woodcut The Kiss (1898) presents a pair of look-alike gender-indeterminate lovers joined at the lips amid an enveloping vortex of luxuriant tresses. This six-color print encapsulates the stylistic essence and psychological undertones of Art Nouveau so effectively that MoMA chose it for the frontispiece of its 1960 exhibition catalog.

2.

A new wave of interest in Art Nouveau is apparently now upon us. One sign of it is the rapturous critical reception of the Guggenheim Museum’s 2018–2019 tribute to the latest retrieval from the dustbin of art history: the mystically inclined turn-of-the-century Swedish artist Hilma af Klint. Some now claim that her visionary nonobjective paintings of circa 1906 made her the unacknowledged inventor of abstraction, a distinction that has usually been accorded to Wassily Kandinsky, whose Untitled (First Abstract Watercolor) dates to 1910. The renewed regard for Art Nouveau is likewise reflected in an increase in publications that differ markedly from those of a half-century ago. Back then, as John Richardson made clear in these pages with his withering review of Robert Schmutzler’s Art Nouveau, these were mostly superficial assessments, prone to silly aperçus such as this:

In Paris and Nancy [Schmutzler wrote], Art Nouveau developed a decidedly worldly character and, not infrequently, had a luxurious quality that even suggests the demimonde. Guimard’s Metro entrances arouse in us expectations of the abode of Venus deep down in a mountain rather than a democratic subway; they seem to lead straight to Maxim’s, the interior decoration of which is still unrivaled as a restaurant interior.1

Today’s more thoughtful authors eschew the Gaîté Parisienne frivolity of those earlier treatments and instead delve into Art Nouveau’s long-concealed substrata, specifically the societal anxieties, disturbed psychic states, and questions of personal identity that not only informed the style but also speak to apprehensions about our own unsettled present and worrisome future. And though some of the artworks illustrated in these books may be quite familiar—including such risqué perennials as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s 1891 advertising poster for the cancan dancer La Goulue and Edvard Munch’s bare-breasted femme fatale Madonna of 1895—the new publications also roam much further afield than their frothy forerunners.

This is true not least in a geographical sense, since the spell of Art Nouveau extended well beyond the well-trod triad of Paris, Brussels, and Barcelona and became a truly global sensation. As an art history graduate student, I used to mock the revered architectural historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock’s typical (and sometimes plodding) country-by-country progress through various styles. He’d sooner discuss Gothic Revival in Andorra, I’d joke, than deliver socially insightful overviews of the sort I craved. But when it comes to Art Nouveau, his approach now strikes me as not so bad, for although this was an international phenomenon, with certain principles that can be identified in the movement as a whole, it diverged in its details from country to country.

For example, much has been made of the effect that Islamic architecture had on early European modernism, particularly the vernacular North African structures that inspired the cubic, white-walled, flat-roofed houses of Adolf Loos, Le Corbusier, and others. But in Art Nouveau the influence went both ways. One crossover is the little-known tomb of Sheikh Zafir Effendi in Istanbul, built in 1903–1904 to the designs of the leading Italian Art Nouveau architect Raimondo D’Aronco. He gave its stylized Islamic detailing a contained feeling akin to that espoused by the Vienna Secession, the breakaway coterie that produced Jugendstil (youth style), Austria’s version of Art Nouveau. And the Vienna headquarters of that group—Joseph Maria Olbrich’s windowless, gold-domed Secession Building of 1897–1899—was dubbed “the Mahdi’s tomb” by local wags because of its supposed (though nonexistent) likeness to the mausoleum of the Sudanese Islamic cleric Muhammad Ahmad, an anticolonialist rebel known by the messianic honorific Mahdi.

Another fascinating rediscovery is the Russian art patron Princess Maria Tenisheva’s collaboration with the artist-architect Sergey Malyutin, whose Church of the Holy Spirit was built in 1903 at her Talashkino artists’ colony near Smolensk in western Russia, not far from the border of present-day Belarus. The wildly exaggerated proportions of this otherwise traditional onion-domed Russian Orthodox structure bring to mind a wonky over-the-rainbow cottage from that American masterpiece of Art Nouveau book design, L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), with illustrations by W.W. Denslow.

Advertisement

The British art historian Anne Anderson’s Art Nouveau Architecture provides a good general introduction to the topic for nonspecialist readers. It includes an unusually large number of excellent color illustrations, although the brevity of her text sporadically crosses over into the perfunctory. She too extends her purview past the already well-known centers of Art Nouveau activity and brings in long-overlooked outliers like Arte Nova in Portugal, Hungary’s Magyar Szecesszió, and the various Romantic Nationalism styles that arose, with distinctive local mutations derived from folkloric traditions, across Scandinavia and the Baltics.

Art Nouveau’s influence reached as far as Japan, which during the last decades of its Meiji period (the imperial reign that promoted rapid Westernization and ended in 1912) proved receptive to a style that had drawn a number of its principles from classical Japanese aesthetics—the flattening of spatial depth, the dark outlining of figures, abrupt cutoffs of the picture plane, and a tendency toward extreme stylization being the most evident.

As part of its invaluable Texts and Documents series, the Getty Research Institute has just brought out a collection of twenty-six previously untranslated essays by the Belgian architect and theorist Henry van de Velde, one of the founding figures of Art Nouveau. His writings on William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement are especially valuable in illuminating the relationship between those successive British and Continental developments, and having his insightful contemporary texts available in English is another sign of the scholarly seriousness with which Art Nouveau is now being considered.

Hector Guimard: Art Nouveau to Modernism is the catalog of a retrospective that has just opened at the Cooper Hewitt and will travel next summer to the Chicago museum founded by Richard H. Driehaus, a billionaire hedge fund manager and collector who died in 2021. (In New York it has the title “Hector Guimard: How Paris Got Its Curves.”) The show draws heavily on Driehaus’s major assemblage of Guimard material as well as works that were given to the Cooper Hewitt by the architect’s widow, the American-born artist Adeline Oppenheim Guimard, a member of the Oppenheim banking and brokerage family. (They married in 1909 and emigrated from Paris to New York in 1938 because of her Jewish heritage.)

One of the catalog’s most fascinating essays, by Sarah D. Coffin, documents Mme Guimard’s strenuous efforts to shore up her husband’s waning reputation and then to memorialize his career in the decades between his death in 1942 and hers in 1965, with shrewdly judged bequests of his works to MoMA, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and other American institutions. As opposed to artists’ widows whose attempts to control their spouses’ legacies have had a baneful effect on their historical standing, she is a textbook example of how to do it right.

All the books under review contain much fresh material that significantly expands our understanding of Art Nouveau, confirming both its broad distribution and its diverse authorship, as well as revealing it to have been far more complex and nuanced than previously believed. Best among the new publications is Art Nouveau: Art, Architecture and Design in Transformation by Charlotte Ashby, a lecturer at Birkbeck College, University of London. Her command of the subject is hinted at in the book’s twenty-page bibliography and is further borne out in her skillful syntheses of ideas from those many sources. But even more impressive are her imaginative leaps. In a chapter titled “The Power of Nature” she discusses a weird and seldom reproduced 1894 watercolor, A Pond, by the Scottish artist Frances Macdonald (a sister of Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh):

In it we see the fusion of nature, science and the spiritual and the rendition of the prevalent theme of the female figure as a personification of nature, this time authored by a woman…. Macdonald’s work is strangely incorporeal, despite the fact that sexual reproduction is a central theme. The symmetry of the curving wings of the women and trailing tails of their hair and the tadpole/sperm surrounding them suggest vaginal imagery. The purple and pinkish-tan colours used are also evocative of human anatomy rather than the blues and greens one might expect of a depiction of pond life….

The overt depiction of sperm, thinly disguised as tadpoles, demonstrated the artist’s familiarity with scientific imagery. The watery medium of A Pond is in fact a reflection on the origins of life in primeval and reproductive fluids. The curiously sexless female figures reveal a challenging reading of the costs to women exacted by the act of sexual reproduction, as the emaciated bodies of the women contrast markedly with the plump, grinning sperm. The ambiguity of the image defies resolution. Are the women mythical water nymphs, dragonfly nymphs sharing their pond with a group of tadpoles or is it in fact human sexual reproduction that is being depicted? The opacity of much of the imagery employed by the Macdonald sisters through their careers was central to their resistance to patriarchal assumptions surrounding both the reality of women’s lives and the representation of women.

Looking beyond the purely formal aspects of Art Nouveau, Ashby’s book confronts several issues that have come to the fore in cultural studies in recent years, including sexual identity, feminism, colonialism, the natural environment, and the art market. Rather than following a conventional chronological format and attempting to cram in as many works as possible, she instead concentrates on a series of well-chosen thematic investigations that have the narrative liveliness of a good lecture, while the entire book coheres as a seamless though selective survey of the movement from start to finish.

The author’s interest in the social implications of Art Nouveau was preceded by the UCLA art historian Debora L. Silverman in Art Nouveau in Fin-de-Siècle France: Politics, Psychology, and Style (1989). This classic study pays close attention to the late-nineteenth-century recognition of the importance of psychology. In Silverman’s epigraph to one trenchant chapter, titled “Psychologie Nouvelle,” she quotes the French physiologist Jules Héricourt’s observation, published in La Revue scientifique in 1889, that “the unconscious activity of the mind is a scientific truth established beyond any doubt…. Even in daily life, our unconscious mind remains under the direction of the unconscious,” an indication that such ideas were current in advanced French circles well before Sigmund Freud popularized them in the early 1900s.

3.

The late-nineteenth-century interest in the intuitive sources of creativity unexpectedly found a direct outlet in art and design that subverted government-sponsored institutions such as the École des Beaux-Arts, which had imposed restrictions on the parameters of artistic expression. As a result, Art Nouveau was distinguished by hallucinatory imagery that teemed with wraithlike figures, fantastical creatures, and exotic flora, set among vaguely defined, mistily delineated spaces that evoked the elusive but haunting illogic of the dream state. These factors all aligned with the otherworldly spirit of Symbolism, the interdisciplinary cultural movement that had its origins in literature, especially the poetry of Baudelaire, Verlaine, and Mallarmé, which exalted forbidden yearnings and uninhibited fantasies of all sorts.

Those charismatic poètes maudits captivated an entire generation of visual artists, including the French Symbolist painters Gustave Moreau (renowned for his lurid visualizations of Salome, a biblical theme that was even more sensationally illustrated by Beardsley in 1893–1894 for Oscar Wilde’s drama) and Odilon Redon (whose bizarre iconography anticipated Surrealism by half a century). Their Belgian counterparts included Fernand Khnopff, who had a penchant for creepy-eyed sirens, and James Ensor, orchestrator of the monumental tableau Christ’s Entry into Brussels (1889), a searing, jam-packed satirical masterpiece that prefigured the chaotic vitality of Expressionism.

But highest in popular renown today among Art Nouveau artists is the Norwegian loner Munch, the undisputed master of urban anomie and existential dread. His fame is owed mainly to that peerless simulacrum of emotional terror, Shrik (The Scream). First created in 1893, with several subsequent versions made by the artist, it has attained an aura of overexposed kitsch akin to that of the Mona Lisa. Nonetheless it still qualifies as a major landmark of Art Nouveau thanks to its neurotically quivering composition, which is built up from skeins of thin, curving lines in contrasting colors that transmit vibrations of almost palpable unease.

In truth, as a visit to the Spanish architect Juan Herreros’s new Oslo museum dedicated solely to Munch’s art (which opened with little fanfare in October 2021 because of the Covid pandemic) will make all too obvious, he was a highly uneven painter, although a printmaker of consistent genius. However, his finest pictures—such as Evening on Karl Johan Street (1892), which depicts a ghostly nocturnal promenade of stunned-looking Oslo burghers who resemble a drugged phalanx of well-dressed zombies—capture a communal state of modern alienation unequaled by any of his contemporaries.

The titillating allure of Symbolism extended to music as well. Among its chief exponents was the French composer Henri Duparc, today remembered, if at all, for his meandering minor-key art songs, a genre once a standard component of classical vocal recitals (and hilariously lampooned two generations ago by the English-Canadian musical comedian Anna Russell in her chanson send-ups such as “Je n’ai pas la plume de ma tante”). Duparc was one of several composers who wrote settings for Baudelaire’s poem “La Vie antérieure” (The Former Life), a highlight of his collection Les Fleurs du mal. But none of those efforts surpassed the revolutionary compositions of Claude Debussy, whose 1894 symphonic poem Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, an ecstatic erotic reverie, was aptly chosen as background music for the Victoria and Albert Museum’s memorable 2000 exhibition “Art Nouveau, 1890–1914,” the largest retrospective ever held on the subject.

The strong emphasis that the Symbolists and their followers placed on their personal experience of the inner life—self-absorbed, even solipsistic to an almost pathological degree—has become the most accepted way of understanding Art Nouveau. Countering that tendency and building upon her pathbreaking book on French Art Nouveau, Debora Silverman has established a larger political setting in “Art Nouveau, Art of Darkness: African Lineages of Belgian Modernism.” In this remarkable three-part series of essays she makes a number of provocative claims that sometimes seem somewhat far-fetched but in the main are quite convincing and convey an astonishing boldness of interpretive vision.2 Here is a topic that fairly begs for book-length publication.

Silverman addresses underestimated considerations that help explain how Belgium—a cultural backwater since Rubens, international superstar of the Baroque, passed from the scene, and an independent political entity only since 1831 (previously it had been part of the Netherlands)—could become an economic powerhouse by the end of the nineteenth century. This transformation resulted from the ruthless exploitation of Africa’s vast Congo region by Belgium’s King Leopold II. He personally owned what was called the Congo Free State—a hideous misnomer considering his brutal subjugation and enslavement of its indigenous peoples—and looted billions in raw industrial materials from it.

Those abundant natural resources found a ready market in Europe and the United States, where Henry Ford was a major customer for Congolese rubber, used for the Goodyear automobile tires that he put on his cars, as well as for other mechanical components. Silverman has unearthed a damning visual indictment of that symbiotic relationship in a 1906 issue of the French satirical weekly L’Assiette au Beurre titled “The Congo Free Graveyard.” It contains a political cartoon that imagines the Belgian monarch importuning a befuddled-looking Uncle Sam with the promise “I will give as much rubber as you require to render your conscience ‘elastic.’” Behind them a dead Black infant is nailed to a prison door labeled Congo, above a sign that warns, Entry to the public forbidden.

Although Belgium has recently experienced its own version of Black Lives Matter, with monuments to Leopold II toppled in much the same way that statues of Confederate generals have been pulled down across the US, the parallels between this dark chapter in Belgian history and the concomitant flourishing of Art Nouveau there had yet to be so directly and damningly linked. Whereas Art Nouveau was known in French by several jocular epithets—such as le style nouilles (the noodle style) and le style Métro (for Guimard’s Parisian subway commission)—Silverman suggests that another nickname, le style coup de fouet (the whiplash style), is most sharply interpreted when applied to Belgian Art Nouveau because of the long leather scourges that were used to flagellate enslaved Congolese laborers into bloody submission.

She sees those hallmark whiplash motifs, which appear in metal handrails, plaster moldings, and many other Art Nouveau architectural and decorative details, as far from coincidental and not at all innocuous. After all, in the Classical tradition it was not unusual for upper-class domestic interiors from Roman times onward to incorporate decorative details that honored the owner’s source of wealth. In eighteenth-century Britain, grand country houses of agricultural magnates often featured chimneypieces embellished with sheep’s heads, chairs with cloven-hoof feet, or walls with plaster reliefs embossed with sheaves of wheat.

Silverman proposes that the schematized tropical vegetation so common in fin-de-siècle Belgian design comprises another triumphalist trophy of the murderous colonial enterprise that enriched the country’s avaricious king and his financial cronies at the cost of an estimated 10 million Congolese lives. This acknowledgment of the dark deeds that financed art that ostensibly advocated individual freedom promises at last to ring down the curtain on a long-cherished but farcical notion. Art Nouveau was not a merry three-decade saraband in which a celestial chorus line of chiffon-clad bacchantes led humankind into an epoch of limitless possibilities for all. We might better understand it as a grand delusion that concealed as much as it revealed.

This Issue

December 22, 2022

Naipaul’s Unreal Africa

A Theology of the Present Moment

Making It Big

-

1

See John Richardson, “Art Nouveau,” The New York Review, November 5, 1964. ↩

-

2

West 86th: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture (Bard Graduate Center, 2011–2013). ↩