This article is part of a regular series of conversations with the Review’s contributors; read past ones here and sign up for our e-mail newsletter to get them delivered to your inbox each week.

In our April 4 issue, Daphne Merkin immerses herself in My Name Is Barbra, Barbra Streisand’s “970-page, indexless brick of a memoir.” From this feat of self-mythologizing emerges “an extended, complex portrait of a woman gifted early on with an extraordinary talent combined with an unyielding drive, fueled by a mixture of insecurity and audaciousness (although the latter never seems to have been hampered by the former).”

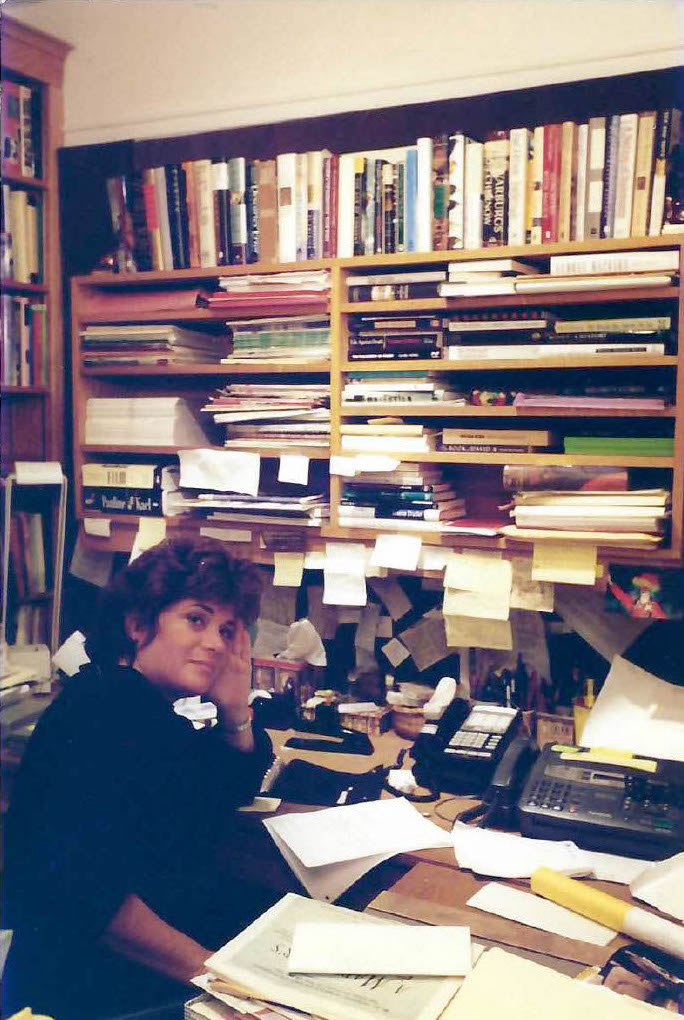

Merkin’s criticism, which often melds a confessional style with extensive reading and intellectual engagement, found a home for many years in publications ranging from Elle to The New Republic to Tablet to The New Yorker. In an essay last year for the NYR Online, she reminisced about the bygone days when glossy magazines were full of writing that took itself seriously while maintaining a certain lightness of touch. In a review from 2021, she looked at how motherhood and writing can coexist (or can’t). Her memoir, This Close to Happy, is a frank recounting of her struggle with depression, and in her recent novel, 22 Minutes of Unconditional Love, a magazine editor recounts a complicated erotic relationship with an older man.

This week we corresponded about divas, songstresses, and pandemic socializing.

Lauren Kane: In 2020 T: The New York Times Style Magazine ran an issue featuring three “divas”: Dolly Parton, Patti LaBelle, and, of course, Barbra Streisand. What does it mean to be a diva? How has that changed? Are there still divas, in either a retro or contemporary sense of the word?

Daphne Merkin: To be a diva, as I see it, is to be larger-than-life—someone who has ascended beyond any one single category that defines them. In some ways, it’s an old-fashioned term and concept, and I’m not sure it easily applies in the age of social media, where celebrity is more casual and has a greater global reach. It seems to me that a certain nostalgia adheres to divaness, an aura of self-conscious glamour: it makes me think of Sunset Boulevard, Marlene Dietrich, and the golden age of the Oscars. I don’t, for instance, think the term applies to Taylor Swift, despite her enormous audience, just as decades ago it didn’t apply to an actress like Ingrid Bergman. All the same, I think there are a few divas left, including several younger ones: Madonna, of course; Beyoncé and Lady Gaga are also examples. Sandra Bernhard, for some odd reason, fits the diva mold. And there is still Streisand, rising above them all in her triumphant eighties.

Anecdotally, Streisand seems to have a charisma that made her attractive to men, despite some of them commenting that she wasn’t a conventional beauty. What do you think that quality is?

I don’t think sexual attractiveness ever comes solely from looks, although in general it does go with a certain level of straight-out good looks, as with Elizabeth Taylor. But it often has to do with playfulness or even slyness. One can be an acclaimed beauty, like Vivien Leigh, and still exude little erotic allure. There’s an elusive quality to it, having to do with an inner sensuality rather than a projected sexiness, and yet it’s very apparent when someone has it. I would say that Ann-Margret (if anyone reading the Review remembers her) had it—one has only to watch her in a film like Carnal Knowledge—and Natalie Wood, despite her vivid prettiness, didn’t. Then there was Angie Dickinson, who oozed sexuality, and Marilyn Monroe, who radiated an almost pneumatic come-hither-ness that went beyond her obvious physical assets.

Coming closer to the present (I grow old, I grow old, as my references clearly demonstrate), there are Scarlett Johansson, Lizzo, Kristen Stewart, and Angelina Jolie. And from a generation before, Diane Keaton. As far as Streisand’s allure goes, I think she hinted at her sexual interest in various men, and it made for a roundabout, come-get-me message that went nicely with her jolie laide looks, which were suggestive of beauty rather than being spot-on beautiful.

You say that when she sings, Streisand “wears the song” rather than “letting it lead her.” What qualities make for a really exceptional singer? You mention Patty Griffin and Iris DeMent—who are some other favorites?

I think great singers seem alone on a stage, holding on to the raft of a song for dear life, singing straight at you. Other favorite singers of mine include Kathleen Edwards, Shawn Colvin, Tiff Merritt, Sinéad O’Connor, Natalie Merchant, Martha Wainwright, Aimee Mann, Rosanne Cash, the McGarrigle sisters. There’s also Lucinda Williams, but there is something stylized about her delivery, breathy and languorous as it is, that gets tiresome.

Your piece alludes to a kind of self-indulgence in Streisand’s memoir—almost a thousand pages, nary a shred of modesty. What do you think she was trying to accomplish?

Advertisement

Streisand’s memoir is as open and honest as a control freak’s memoir can be. She wants it both ways—to let us into her thoughts and feelings, but also to manage her disclosures in such a way that we can’t make any assumptions about her that she isn’t already aware of. We can’t, in other words, think we know her because she isn’t to be known. She eludes the reader’s grasp in the welter of information she provides, words tumbling after words, all of it adding up to a slightly manic narrative that seems intimate while maintaining its distance.

During the pandemic you wrote several pieces for us about social trends: the return of the phone call, getting dressed up for no reason other than to make yourself feel better. Have you noticed if these trends have persisted or died off? Was the pandemic in some instances socially restorative? Did we lose that?

I do think the pandemic was (paradoxically) socially restorative for many of us, allowing us to connect in a more leisurely and less reflexive fashion. I, for one, was happy to welcome phone conversations back into my life; I had missed them. Meeting a friend in Central Park seemed like a triumphant overcoming of obstacles, an occasion to be celebrated. In addition to the physical isolation that Covid imposed, it also offered a ready avenue into existential musings on the meaning of life, the imminence of death, the aloneness at the center of social intercourse. With the end of the pandemic, phone calls have largely disappeared and the impulse to dress up for no reason at all has abated.

Your last review for us dealt largely with the question of writing and motherhood. How has motherhood shaped your career?

I’m not sure motherhood has shaped my career so much as informed it. Before I had my own daughter, I had been a very involved aunt to twenty nieces and nephews. I was aware of the strong pull of being around young children and the effect it had on me, losing myself in their pleasures and dilemmas. In all candor, being a mother elicited an ambivalence in me that I didn’t have about being an aunt because of the commitment that came with it, the need to be there always and forever, which induced some claustrophobia (as did my marriage). But it also brought into perspective things that might otherwise have loomed large—took the edge off my ambition, such as it was.

I had never wanted or had it in me to devote myself undistractedly to writing or editing or reading, and I was happy to attend to the large distraction of having a child. As I wrote in that review of several books about motherhood and writing, I never felt that being a mother forced me to cut back on the attention I paid to a literary career. I still believe, as I wrote then, that having more than one child (which I didn’t, for a variety of reasons) might have made my writing time all the more to be honored instead of frittered away, as I am sad to say is often the case.

What are you reading right now?

I’ve just finished a new biography of Carson McCullers, which in turn sent me back to some of McCullers’s novels, like The Member of the Wedding and The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter. I had loved them when I read them in my twenties, but this time around I found both of them slightly irritating in the lushness of the descriptive prose and the unwavering focus on freaks and freakishness. For a depiction of oddness and outsiderness, I prefer the writing of Jane Bowles, especially Two Serious Ladies. I also read a l-o-n-g novel by Nathan Hill called Wellness (terrible title), which I enjoyed and admired for its ambition, although I could have done without the section on algorithms, about which I’m still mostly in the dark. I also read not long ago the multivolume Cazalet Chronicles, by Elizabeth Jane Howard, which are quite dazzling in their sustained ability to create a world that is persuasively its own. Then there are the latest issues of the TLS, The Atlantic, The New Yorker, The Literary Review, and our very own NYRB.