A young woman from Reno, an artist (and motorcyclist), comes to New York and the Seventies downtown art scene, and is promptly dubbed “Reno” by one of the art scene people. That’s the starter motor for Rachel Kushner’s novel. Reno is intelligent. She is shy and bold. She is attractive. She has a winning gap between her front teeth. She wants to do her art. She has brought the American West east. Here she is, alone in New York, a bit at a loss. She is looking for her story. She is the story, or rather hers is the voice that tells about many of the events in the book and inspires much of the dialogue of the other characters. She connects what’s in the novel to connect.

The other principals are Sandro Valera (fleeing his distinguished Milanese family whose factory in Milan makes Moto Valera motorcycles) and his friend Ronnie Fontaine, with each of whom Reno has an affair, and to both of whom, but especially to Valera, Reno joins herself, heart and head. Both fellows work as nighttime security guards at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, or did in the recent past, and of course there’s a scene in the empty after-hours museum examining a Greek statue of a slave girl, with meanings attached. Both men are artists. As to whether Reno is an artist. As to whether any of these artists are artists. Ah well. I’m sorry to say that these lively combustible characters, quite fun, talkative, talkative, up to all kinds of stuff, whose names are mixed in with the names of real artists of the period (such as Robert Smithson and, for heaven’s sake, Morton Feldman!), these fictional artists and art world types are not really persuasive, even when they supply pages of pleasure.

The book begins with a flashback to World War I, with an Italian soldier at the front yanking the headlight off the motorcycle of a buddy who a moment before has crashed and died, and using the headlight as a cudgel to knock down a German soldier charging toward him. The Italian soldier is T. P. Valera, Sandro’s father, as a young man. At intervals during the course of the novel, the story of the father is told, how he made his fortune with rubber (and therefore tires) produced by what you could call slave labor in the jungles of the Amazon, leading to a company and a factory in Italy, and prestige and power.

The father as a youth, well before the war, falls in with a spirited gang of kids in Rome who hang out at a particular café and make proclamations about life and art and politics, and blast around town on their primitive early motorcycles, and whose attitudes and activities and aggression are meant to bring to mind the Futurists and forecast the fascism to come. It doesn’t convince. Not quite. Not really. Are they also meant to foreshadow, however dimly, the virulent, violent Red Brigades, seventy years in the future, and in the future of this novel? One of the problems of the book is that while lots of people in it have lots to say about many things, important things included, the things they say never sound like what real people might say, like real thoughts or real speech. The book keeps being entertaining (except for the really bad bits) and keeps being unconvincing.

The Flamethrowers has been praised in many places for the vivacity and invention of its language, for the bulging vitality of its characters, for the landscapes and settings and action, urban and otherwise, Italy, America, Nevada, New York, over a hundred years of action and story. Why not! All true. Deserving praise. But to me the novel too often sounds like the stylized voice-over narration of film noir, sardonic, self-conscious, very American, the sound of Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Fred MacMurray in Double Indemnity. Which can be very entertaining when it’s Chandler or Hammett but when it’s not can seem awfully artificial. Talk, talk, and talk. A bunch of arty tough guys, male and female, talkative American Noël Cowards—everybody has something smart to say.

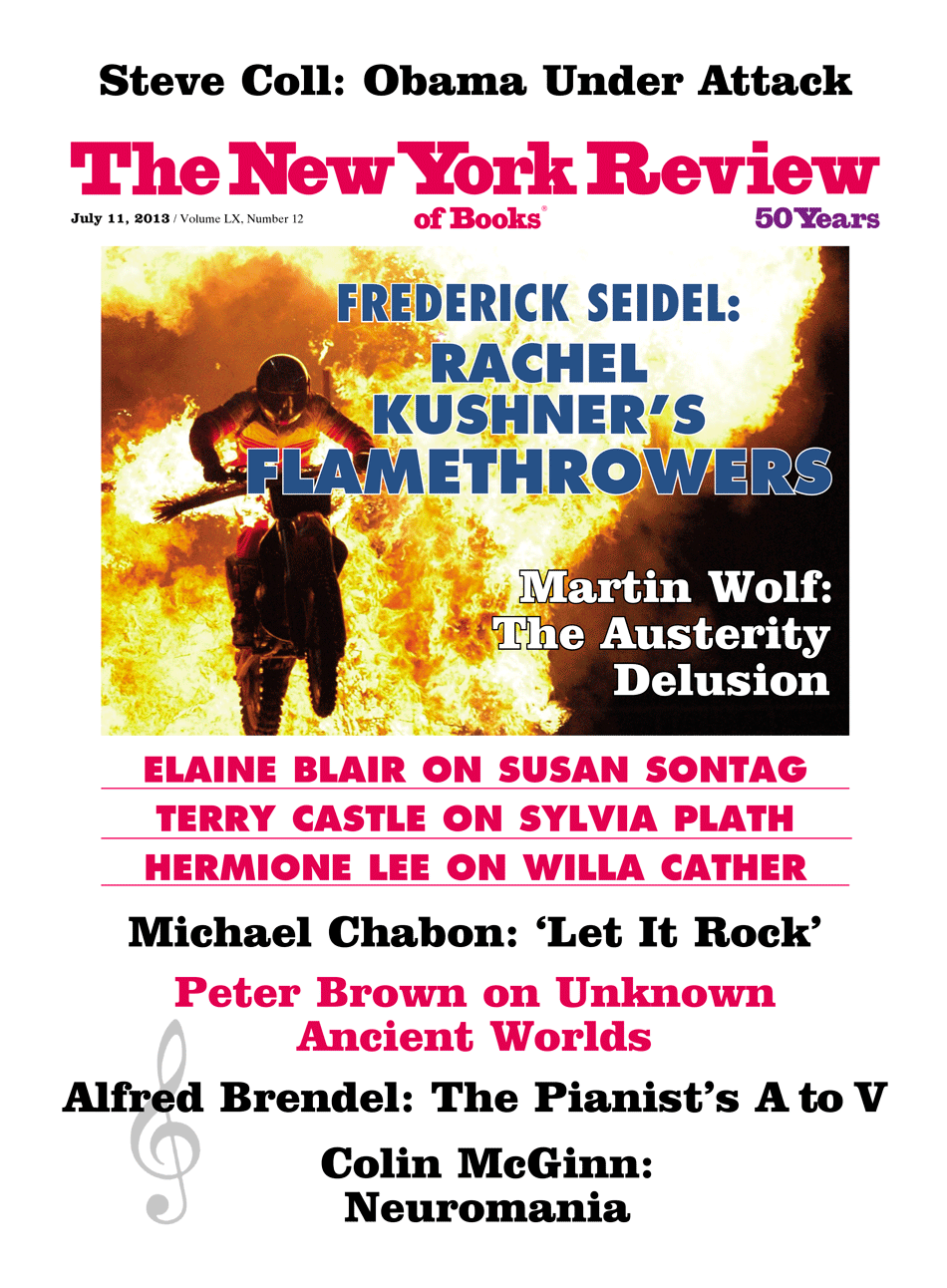

I thought at first I was reviewing this book because of the motorcycles in it. They are not very convincing motorcycles, nor are the accounts of how it feels to go fast particularly convincing. I like motorcycles. The race bikes I myself have ridden have mostly been Ducatis, made in Bologna, Italian. The fictional motorcycle in the book is Reno’s Moto Valera, Italian. I thought I was reviewing this book also because of the Italy in it, some of the Italy superbly done, some of it not so much. There is a lot in The Flamethrowers that is tiresome, histrionic, hysterically overwritten, desperate to show how brilliant it is, a fatiguing endless succession of arrestingly clever similes to describe personalities and situations, similes, similes, cleverness, cleverness, slowdowns of yawningly long bravura description, speedups that sound like sitcom.

Advertisement

But there is also a lot that is really quite wonderful, the good side of the bad side, a romantic splurge, a brightness of colors, an ambition to tell a big story. The book is too long—it needed an editor it obviously did not have—but when it’s on song, as we used to say in the world of motorcycles, it’s joyful, it’s youthful, it zooms. But it’s still first-person singular. It still talks too much. So much description. So many soliloquies. So many one-liners in the midst of all the other talk.

Reno has an idea. She will ride across Nevada to the Bonneville salt flats where she will attempt to set a speed record (for motorcycles in its class) on her Moto Valera. That attempt will be her art, the invisible straight line of her going very fast will be her art. But she crashes when she makes her run. But she’s all right. Hardly hurt at all. There are charming and amusing portraits of the people who go after land speed records and nice stuff about the official Valera team and their diva driver under his hairdo before he puts on his helmet. His name is Didi Bombonato and he is seeking the world speed record in a two-wheeled metal cigar with a rocket engine, called Spirit of Italy.

There’s a nice bit of comedy and Italian reality in how a work slowdown back at the motorcycle factory in Milan all of a sudden makes it impossible for the team of mechanics around Didi to proceed at more than a snail’s pace. I suppose there are people in the world with names like Didi Bombonato, particularly in the Mafia and the vanished world of burlesque dancers. I suppose. Just as in the real world there are people with names like Ronnie Fontaine. And John Dogg. And Giddle. And Talia Shrapnel (Sandro’s cousin and lover, a descendant of Henry Shrapnel, the inventor of the shrapnel shell, who changed her ugly original name to Valera, her mother’s name).

Here’s the point about the names. There is a generous and exuberant artificiality to this book, as I have mentioned, and, as with the names, a comical exaggeration, but one that isn’t always funny—Terry Southern without the laughs. There’s a tremendous comic energy in the characters in the book, a downtown outlandishness, comic but usually not funny, brilliant fiery invention, but somehow lacking in feeling. The book has heat but lacks warmth.

What is this book interested in? Besides motorcycles. Which it’s interested in only a bit, and, as much as anything else, as a plot device, yeast to make the rest rise. It is interested in language, but that interest it doesn’t quite have under control. Language runs away with itself, runs on, hopped up. What’s the book interested in? Would that be Art, or rather the making of art, or rather how some of the people trying to create lived in New York in the Seventies? It’s a novel, so it’s interested in the people. It adds politics to the people. This was the period of radical politics in major cities of the Western world, so you have the character Burdmoore and his wittily named Fah-Q movement. The Symbionese Liberation Army gets mentioned, the East Village Hell’s Angels are there, Patty Hearst flashes past. You get speechifying. You get drinks and hijinks and girls. Banks get robbed, an offending landlord gets killed. But mostly the scenes take place at parties, in clubs, in a diner, the Trust E, in Rudy’s Bar. The scenes are like movie storyboarding or like panels of a comic book, puffs of bright illumination in many colors, as in the sequencing of a fireworks display.

There will be more politics, radical politics, and serious, deadly, bad unpleasantness when the book gets back to Italy from New York with Reno and Sandro, and where the Red Brigades are (so to speak) waiting.

On the basis of Reno’s speed runs at Bonneville—a second run after her crash, but this time in Bombonato’s borrowed Spirit of Italy, gave her temporarily the world land speed record for a woman!—Reno gets invited to ride for Team Valera back in Italy. A very reluctant Sandro decides to join her and return to Italy to face his family, which means older brother Roberto who runs the Valera company, the father having died, and the dreadful mother. And here they all are, including Sandro’s cousin, the formidable Talia Shrapnel Valera, at the grand family property on Lake Como.

Advertisement

The fun of the novel is about to end—two hundred pages before the novel actually ends—but not without a few scenes with these pampered grotesques. Haughty awful mother and her fool of a lover, extremes of class nonsense. Roberto, emblematic, coldly arrogant industrialist. And the servants, who, like the mother, treat Reno with disdain. The servants are standard-issue servant snobs, devoted to the family, and make a nice contrast to the not-at-all devoted Valera factory workers who are about to thrust themselves forward in the story. The work slowdown at the Valera factory has turned into a workers’ insurrection. Soon much of Italy will be involved. Reno is not going to be able to make her Moto Valera run, is the very least of it.

A handyman working at the Como estate—Gianni—taciturn, charismatic, Reno’s age, will turn out unsurprisingly to be a member of an extreme radical group. Reno, fleeing Sandro, who has betrayed her with his cousin Talia—sounds like program notes for an opera, right?—will leave with Gianni and travel to Rome and, without wishing to, will become part of the radical uprising there—will be a nonparticipant witness, a noncombatant caught up in the violent demonstrations and destruction.

The novel is turning into the needs of its plot. The plot is stepping forward as a character in its own right, as in opera. There are crowd scenes out in the city, in the streets and piazzas, and domestic scenes and drama in the secret apartment where the radicals nest. We know what happened in Aldo Moro’s Italy, terrible things. None of what’s happening to Reno seems real because it isn’t. It almost is, it wants to be, or wants to seem to be, but isn’t. It wants to be more, it wants to invent to the level of persuasive reality, and still be a novel. But it’s only a novel, Kushner’s novel, and feels like it, reads like it. She brilliantly tries. She writes like mad. There is the news that Robert has been kidnapped. Later there will be the news that he has been killed. Now we are looking up at the Italian Alps into which the escaping Gianni disappears, and now we are waiting with Reno on the other side, the French side, for him to reappear. He doesn’t.

Now we are back in New York, at the end of a four-hundred-page swirl and whirl of language and people and bits of business, bomb blasts and jukebox music—and Morton Feldman with his thick glasses—and “‘Larry Zox, Larry Poons, Larry Bell, Larry Clark, Larry Rivers, and Larry Fink. And they’re all talking to one another!’” So much New York, so much Seventies, such bursting-apart-at-the-seams liveliness! What a splendor of invention! These passionately alive and not believable characters! Heat without heart. Such an abundance of life and liveliness and language! It’s a glorious novel Rachel Kushner has written with heat but without warmth. Maybe that’s a new kind of novel.

The end, the final pages. And we’re back in Rome. Learning why the Allies bombed the Cinecittà film studios during the war. And, look, we’re in the Saarinen TWA terminal at JFK, which makes Sandro think of Brasília, built with T. P. Valera’s rubber-tapping money. And now Sandro thinks about Talia, who talked like Sylvia Plath and looked a little like her. And now we’re with Reno waiting below Mont Blanc for Gianni to reappear, as the lights of Chamonix come on and snow falls and night falls.

What’s this book interested in? It’s interested in being made into a movie.

This Issue

July 11, 2013

A Pianist’s A–V

Hard on Obama

The Unbearable