Among the things which Günter Grass is good at—as he might put it, in one of his less engaging habits of phrase: writingsculptingdrawingtalktalkingbarbilliardstombstonemaking—there is cooking. He comes back to cooking several times in From the Diary of a Snail, not to a classic cuisine or to Utopian rinds and grains, but to great thick cauldrons full of Central Europe’s fancy: tripe with caraway seeds and tomatoes and garlic, mutton with lentils, “green eel” from the dirty old Havel lakes, beef heart stuffed with prunes, pheasant with weinkraut, hashed lung. Novels are a sort of soup, drawn out of every kind of bone, stray vegetable, and stock from past meals. In the present case, however, Grass has chosen to serve up the ingredients with their end product. We get a novel, a central narrative, and interleaved with it an assorted mass of diary, fantasy, and reflection.

In 1969, Grass for the second time fought an independent election campaign on behalf of the Social Democrats. As he had done in 1965, but on a much larger scale, Grass toured the country speaking in one small town after another, encouraging the growth of voters’ clubs and daring the doubting electorate to return Willy Brandt, a “Sozi,” as chancellor. (Brandt did become head of a government, but only as the leader of a coalition with a perilously thin majority: it was not until 1972 that the West Germans showed unmistakably that it was a Social Democrat government that they wanted.)

But for the first time, Grass found himself fighting on two fronts: against the sullen, familiar mass of Christian Democrats and conservatives on the right, but also against the new left, the revolutionary young whose insurrection the year before had shaken the whole state on its foundations. Accustomed enough to being called a criminal against Germanity and a befouler of the national nest, Grass reacted badly to being denounced as a revisionist by boys and girls in brass-framed glasses. He hit back, sometimes with bad-tempered invective which evaded the fundamental questions thrown at him, but at the same time he began to reach around for a more coherent and profound way of expressing his own revulsion—so typical of the generation of teenagers who were sucked into the Wehrmacht—from German radicalism and “the weeds of German idealism which spring up as inexorably as rib-grass.” One result was the intemperate Local Anaesthetic, his least successful novel. The second, much more interesting, is From the Diary of a Snail.

One can list the ingredients before trying to describe the soup. Much of the book consists of his diaries from 1969; fragments of the campaign with all its encounters and journeys and hotels; reflections on days and weekends snatched with his wife and children in Berlin; sketches of Willy Brandt silently playing games with matches in a melancholy of self-doubt and then emerging at last to fight; a visit to Czech friends a year after the invasion. At one meeting Grass addressed, a man made a wild speech greeting his old comrades of the SS and then took cyanide: Grass sought out the man’s family and found himself among the relics of an idealist, a seeker after Gemeinschaft, a man who had joined every kind of movement from the SS to Ban the Bomb, and had never learned philosophy from each successive disappointment. For Grass, that terrible gesture reflected the slighter defiance of a young Social Democrat at another meeting who stood up and slowly, very elaborately, tore up his party card.

Another ingredient is an engraving, Dürer’s Melencolia I, the picture of a woman angel seated chin on hand, glaring disconsolately at nothing, the emblems and tools of time and construction lying abandoned around her. Grass had been invited to give a lecture on Albrecht Dürer, and this was the work which came to obsess his imagination during the election campaign. The lecture which he ultimately delivered stands at the back of the book, proposing that sullen angel as the essentially humanist recognition that things are difficult, progress slow, discouragement inevitable. Against Melencolia he puts “her sister Utopia, always on the road,” “invoking redemption,” the belief that everything can be transformed, a “Neue Mensch” brought to birth, all delays and obstacles swept aside by the power of an abstract idea. Sister Utopia is the patroness of those whom, in another passage, he calls “people who want to bend the banana straight for the benefit of mankind.”

A third hunk of presented experience is the writer’s visit to Israel. Here again he met his idealists, Orthodox groups who harassed audiences for consenting to listen to a German writer. More importantly, he went to find the survivors from the Jewish community of his own home town, the prewar “Free City” of Danzig, and set down the annals of their persecution under the Nazis: their efforts to keep some education, some welfare services going, and their final destruction.

Advertisement

Out of all this comes the central short novel, yet another book about Danzig with Grass’s usual combination of the realistic and the fabulous. Hermann Ott is a young schoolmaster with a learned passion for snails and slugs. He admires their beauty and variety. But most of all he respects their slow, hesitant, erratic tenacity, their passage through every kind of error and delay to their goal. The snail fancier (whose nickname, a bit obviously, is “Doubt”) falls out with the Nazis and is gradually drawn to their victims. His fiancée throws him over for consorting with Jews; an old lady stabs with her hatpin the lettuce he has deliberately bought at a Semitic stall. Ott teaches at schools for the dwindling Jewish community in Danzig until the last group of emigrants departs on the eve of war.

The police become interested in this person with a snail philosophy who does not appreciate “the good fortune to live in great times.” Ott is summoned several times to headquarters and given some preliminary slapping-about. One quiet day, he takes his bicycle and few possessions and pedals by back streets out of Danzig. He lands up at Karthaus, the country town of that evasive little Slavic minority called the Kashubians from which Grass himself comes, and persuades a Kashubian cycle dealer named Anton Stomma to hide him in his cellar. And in Stomma’s cellar he remains for the rest of the war.

The seasons drag by. His money runs out, and Stomma takes to beating him periodically with his belt; you take in a fugitive out of a muddle of pity and cupidity, and then he stops paying and it is too late to tell the police. But as the war news turns slowly against Germany, matters in the cellar improve. Stomma permits Ott an armchair, and as a gesture of hospitality sends him nightly his daughter Lisbeth. Steeped in melancholy after the death of her illegitimate son, Lisbeth is wordless and frigid. Her only pastime is visiting cemeteries. But by a grave she discovers a brilliant slug of unknown species. Ott sends it crawling over her indifferent body, and gradually it draws out of her the dark humours. She begins to talk, then to respond to Ott’s dogged churning at her loins. She becomes a chatterbox, gets an awful permanent wave, throws cantankerous scenes, and starts litigating for the possession of another muddy smallholding.

The slug of redemption has now turned an ugly black, swollen with her transferred Schwermut. When Lisbeth manages to put her foot on it, it bursts with a repulsive plop and vanishes from the narrative. The Russians and Poles arrive; Stomma and Ott become petty bigwigs of the new administration; Lisbeth marries Ott and nags him normally ever after.

So there is the fable of the snail, the ode to the unheroic, disappointing, and often disappointed men and women who creep reforming through the common mud rather than taking wild wing toward revolution. The Social Democrat as gastropod; Willy Brandt as humanist melancholic fiddling with the matches on his desk. How often Grass has written and spoken about his affection for the very shabbiness and “colorlessness” of his party! He has never made the case so cleverly and persuasively as here. Even the incessant collisions at the corner of his Berlin street are turned to effect. His son asks: “If a blue and a yellow Volkswagen crash, will they be green?” Grass notes: “When the colors declared war on each other, gray was the peacemaker.”

Any book in which at least four themes succeed each other paragraph by paragraph becomes irritating at moments. From the Diary of a Snail bulges with indulgent asides, and there is a fair amount of mildly boastful stuff about Grass’s personal intimacy with presidents and chancellors which has infuriated those who assume that if Gustav Heinemann and Willy Brandt called round at their place for a glass and a cigar, they would not stoop to recording the fact in print. And yet this book is a whole. The tale of Ott and his slug is masterly, but not strong enough to stand with great distinction on its own. One becomes fascinated, as Grass intends, by following the relationship between the soup and the bones.

But does he prove his case? It happens that this book came out in the United States only two weeks after that eleventh of September in Santiago de Chile, on which Salvador Allende died and the slow, glistening trail of his advance toward justice and democracy ended. Allende, if anybody, was a snail in the best sense of the word. But he was caught in the open by the rapacious birds. The workers, strong in numbers and spirit, were in their own snail shells, barricaded in their factories on the outskirts of Santiago or Concepción where the army could smash them one by one.

Advertisement

It is not always safe to move slowly. And it is not always immature, obsessional, contrary to humanism to wish to move fast. One turns back to one of the many diatribes against the revolutionary left which Günter Grass sets into this book:

They want to change other peoples’ consciousness before their own: sons of too-good family who go into ecstasies about the proletariat…soured pedagogues who stretch their idealistic soup with a shot of Marxism; daughters of the upper classes on the lookout for an exclusive left-wing tennis club; more recently, professional soldiers of the Cross, who dispense the blood of Christ in Hegelian bottles….

In Chile on September 11, the Dutschkes and Reverend Professor Gollwitzers, the Baaders and Meinhofs of Chile were asked to honor their bond, after so many of them had begged the snail to take wings and outpace its enemies. The students of Santiago, the clever, discontented boys and girls from well-off momio families, the Marxian priests fought and died with their proletariat that day and on the days that followed.

With all Grass’s imaginative power, there is a perspective which he lacks and Germany lacks, and which other European countries find it easier to comprehend. This is the experience of resistance to tyranny. When the Nazis came, these countries often passed into the trusteeship of men honest and snailish by their own lights, who sought to preserve what could be preserved, to spare their peoples the suffering which useless defiance would bring. They had to deal with irresponsible young men and women, who lacked experience of the world, who did not know where to stop, who said No to all compromise, who looked toward a faith and looked away from the misery their actions brought upon the mass of the fellow citizens: so, at least, it seemed to many in 1940 or 1941. Five years later, the survivors of those Utopians came down from the hills and were seen to have saved and increased what was most valuable. Willy Brandt himself once left his snail shell and fled abroad to join a foreign resistance to his own country. When Melencolia ends her brooding, who knows if she will not use her wings?

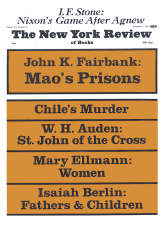

This Issue

November 1, 1973